Greenland is an autonomous country in the Unity of the Realm – a national community with Denmark and the Faroe Islands. It is the world’s largest island with an area of 2,486,000 km2, a distance from north to south of about 2,670 km and a total coastline of more than 44,000 km. About 80 % of the country is covered by the ice sheet. At the same time, it is the world’s most sparsely populated area, with a total population of only about 56,000 people. Along the coasts, an area of well over 410,000 km2 is ice-free, and this is where the population lives in towns and settlements. Today, more than 70 % live in the seven largest towns: the capital Nuuk and the towns of Sisimiut, Ilulissat, Qaqortoq, Aasiaat, Maniitsoq and Tasiilaq, but originally, Inuit lived in small hunting communities. Greenland’s neighbours are Canada to the west and northwest, Russia on the other side of the North Pole, and to the southeast is Iceland and then the Faroe Islands, Norway, Denmark and the rest of Europe.

Greenland has a long formation history, which includes virtually all types of geological processes throughout Earth’s geological history. From cracks in the contiguous supercontinent of Pangea 175 million years ago to giant layers of lava from Earth’s interior ten million years ago, which have formed an up to 7 km thick basalt layer. But first and foremost, it is ice that characterises Greenland. The ice sheet has covered the island for about seven million years, but its prevalence has varied due to changing glacials and warmer interglacials. Glaciers and ice streams from the ice sheet reach out towards the sea, forming large icebergs such as at Qeqertarsuup Tunua (in Disko Bay). The ice sheet has long been the subject of interest by international researchers, and the link between increased melting and global warming has only strengthened interest. Greenland has mineral deposits of coal, lead and zinc, and attempts have also been made to extract platinum, gold and uranium. There are polar bears and muskoxen in parts of Greenland, but it is especially life in the sea that has given the Inuit the gifts of nature and thus their livelihood: whales, seals, fish and shrimp.

PAUL ZIZKA PHOTOGRAPHY/CATERS/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2016

The first people immigrated to the country from Siberia, Alaska and Arctic Canada about 4,500 years ago. Then Icelandic Vikings arrived, who settled as peasants in the southwest and adopted the name Greenland. In the late 12th century, Inuit immigrated from Alaska to Greenland, laying a foundation for today’s population. In the Nordic view, Greenland was part of the kingdom, and therefore in 1721 the missionary Hans Egede arrived, supported by King Frederik IV and by Norwegian traders, and now began a concrete colonisation of Greenland with a Christian mission and the construction of trading posts along the west coast of Greenland.

The key to the colony project was blubber from Inuit whale and seal hunting. Originally, the blubber was used by the family and the settlement, and the catch was an important part of Inuit culture. Now the blubber was made into a commodity and part of international trade. By the late 19th century, the market lost interest in blubber; fishing industry was now to replace seal hunting, and the country faced a massive wave of modernisation according to the Danish role model, focusing on urban development. Lots of Danish labour was now to be used in construction, education and administration in particular.

The Danisation, as it was called, brought improvements in some areas, but also triggered frustrations, resistance and desire for secession. A Greenlandisation sprouted with greater interest in traditional Inuit culture. The rock band Sume saw the light of day and gained great popularity with songs in Greenlandic. In 1979, a referendum led to the introduction of the Home Rule, and in 2009, a self-government arrangement for Greenland replaced the home rule arrangement. The self-government covers most internal affairs and can be extended to, for example, independent police, legal system and border control, while foreign, security and defence policy are not covered, as that still falls under the Unity of the Realm.

Greenland is administratively divided into five regional municipalities, containing a total of 17 towns and 54 towns and settlements spread over an enormous geographical area. There are no road connections between the towns and settlements, so transport is by sailing and flying and in some places by snowmobile. In North and East Greenland, dog sledding is also used. The long distances and sparsely populated towns and settlements mean that Greenland is characterised by island communities, where each town and settlement has to be self-sufficient in terms of all societal functions, such as electricity, school, health care, shopping, etc. Politically, priority is given to a welfare society combined with continued dispersed towns and settlements outside the towns. Usually there is no market platform for private companies in the small towns and settlements, which is why many services are provided by the public sector.

Greenland has always been the subject of outside attention. The Danes have left their clear mark, but the Americans, too, have had a big impact. During and after World War II, in which Denmark was occupied by Germany, the United States established a number of military facilities and had thousands of soldiers in Greenland. Today, the global climate debate focuses on the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, and the location and resources of Greenland are key to the geopolitical ambitions of several nations for the Arctic. In future, global interest in Greenland will only be reinforced.

Globalisation is happening at the same time as a renewed interest in traditional culture. This is manifested, for example, in Greenlandic art and culture. The traditional drum dance and song have thus regained great popularity and is on the UNESCO World Heritage List for Intangible Cultural Heritage, while in the more recent visual arts, movements away from the national narrative can be seen. The combination is seen, for example, in Greenlandic fashion and design. Where previously, mainly products that referenced Greenlandic culture were created, the gaze is now turned to more global trends – while using the traditional symbols of the Inuit. Greenland is important to Inuit. And to the world.

The meaning of the place name

The name is known from 1075 when Adam of Bremen is the first to mention a Gronland. In Norse sources from the 12th century (Islendingabok and Landnamabok) and the 13th century (Groenlendinga Saga and Erik the Red Saga), and in preserved later transcripts thereof, the name appears in the forms Grænland and Grønland. In a Danish language context, the name appears as Grønland in the 16th century. The name is a compound of the Norse adjective grǿnn »green« and the noun land »land area, large island«, with the overall meaning »the green land area« or »the large green island«. The choice of name is explained explicitly in Islendingabok, which states that when Erik the Red, exiled from Iceland, discovered and settled in Greenland in the 980s, he decided to give the place a good and alluring name, so that others would also want to move there. In addition to the name’s real estate value, the somewhat milder climate of the Viking Age is also thought to have helped justify the name, as the southern tip of Greenland was lush and grassy and allowed growing grain in the summer months. In the clerical administration of the Middle Ages, Greenland constituted its own diocese with the name Garðar, which is a plural form of the West Norse noun garð »farm«, named after the place in the Eastern Settlement where the episcopal residence was located (near what is now Igaliku).

In modern Greenlandic, Greenland is called Kalaallit Nunaat »Land of the Kalaallit people«, named after the largest Inuit ethnic group in the country. Older sources also use the name Inuit Nunaat, Land of the Inuit.

Coat of arms of Greenland

A polar bear is the obvious choice for a coat of arms for Greenland, and in 1666 the polar bear was added to the royal coat of arms of Denmark as the arms of Greenland. Since 1819, the arms have been permanently depicted on the royal coat of arms of Denmark.

The coat of arms is used by the Danish authorities in Greenland with the royal crown on the escutcheon. The Government of Greenland and the Greenlandic authorities use the coat of arms without the royal crown and with the polar bear’s left forepaw raised, in contrast to the Danish authorities, who use a version with the bear’s right forepaw raised. The two versions of the weapon were adopted in 1987, at which point a Greenlandic wish to have the polar bear raise its left forepaw was allowed, since a polar bear always uses its left forepaw to defend itself.

Blazoning (description): Against a blue background, an upright seated silver bear with a red tongue.

Erfalasorput – The flag of Greenland

The flag is designed by the Greenlandic painter and visual artist Thue Christiansen. He became Greenland’s first Minister for Culture and Education in 1979. He has described how the flag symbolises the ice and the sun, and the red and white colours show Greenland’s ties to Denmark and the Danish flag, Dannebrog.

Greenland was given home rule in 1979, at which point the question of a Greenlandic flag became relevant. Several proposals were submitted in the 1970s, and in 1980 the Greenland Government arranged a flag competition. More than 600 proposals were submitted. However, a flag committee headed by Greenland’s first prime minister, Jonathan Motzfeldt (1938‑2010), failed to come to a decision.

In 1984, it was decided to choose between two different designs: Thue Christiansen’s red-and-white flag with the sun disk and a Nordic cross flag, green with a white cross, proposed by the Danish editor and heraldist Sven Tito Achen.

There were three main positions in the debate on the Greenlandic flag: One group wanted a flag inspired by the Dannebrog, which would be reminiscent of the Danish Realm and the Nordic collaboration. Another group wanted a flag without a cross, which would emphasise the uniqueness of Greenlanders as Inuit. Finally, some wanted the Dannebrog to remain the only flag in Greenland.

The idea of a referendum was abandoned. Instead, in 1985, the Greenland Parliament made a decision by ballot. Christiansen’s flag won with 14 votes, Achen’s flag received 11 votes. The new Greenlandic flag officially flew for the first time on 21 June 1985.

Today, the Erfalasorput is a national symbol that unites all Greenlanders and is seen everywhere in towns and settlements and on vessels registered in Greenland. In Denmark and the Faroe Islands, anyone can fly the Greenlandic flag without special permission.

The appearance and use of the flag is regulated by an act of parliament from 1985. An executive order from 2008 sets out a number of official flag days on which flags are flown from public buildings. The national authorities in Greenland, including the national ombudsman, the courts, the defence and the police use the Dannebrog as a swallow-tailed flag.

Nature and landscape

ALEXANDER BENEDIK/CATERS/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2017

Greenland has an area of just under 2.5 million km². Lying between the 59th and 84th latitudes and the 11th and 74th longitudes, the country is bounded on the west by Davis Strait and Baffin Bay, on the northwest by Smith Strait and Nares Strait, on the north by the Lincoln Sea and the Wandel Sea, collectively known as the Arctic Ocean. To the east, the country is bounded by the Greenland Sea and the Denmark Strait, and finally on the south by the Atlantic Ocean.

Layer upon layer of snow and ice forms the ice sheet. With a volume of about 3 million km³, it covers about 81 % of Greenland. This makes the ice sheet the world’s second largest freshwater reservoir – second only to Antarctica at the South Pole.

Most of the year, temperatures are below freezing, but should the ice sheet melt, it will equate to a total global sea mirror rise of seven to eight metres. The central part of the ice sheet is about 3,200 m above sea level, and from here excess ice moves towards the coast, where the ice calves off in or near the sea to form impressive icebergs.

A stable high pressure is often formed over the ice sheet, which means that the ice sheet not only dominates the island’s climate, as low pressure from the west is pushed south, but also affects the further course of the low pressure passages and thus affects the weather in Europe.

STEFAN EISEND/LOOK/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2008

Greenland has been covered by the ice sheet for millions of years, but its distribution has varied considerably in step with changing glacials and warm interglacials in the last two million years. During the last glacial period, the ice sheet covered all of the country, and in most places, it extended into the ocean. As the ice retreated to its current position, it exposed the Greenland glacial landscapes, which are similar to those known from many places in Iceland and Denmark. Since then, the landscape has been characterised by a number of minor changes, and the cold winters have caused the permafrost to spread to more than 80 % of the present ice-free part of Greenland.

The ice-free part of the country (equivalent to 410,449 km2) extends 2,670 km from Greenland’s southern tip, Uummannarsuaq (Cape Farewell), to the northern tip, Cape Morris Jesup. Uummannarsuaq is located at the same latitude as Oslo. Greenland is the northernmost contiguous land area on Earth.

LARS K MIKKELSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 1996

The ice-free part of the country is similar in size to Sweden and constitutes an up to 250 km wide zone along the coast. Here the geology is exposed and dominated by a shield of a Precambrian bedrock, which, for example, in the Isua area near Nuuk in West Greenland consists of crystalline rocks, which are considered among the world’s oldest rocks. On several occasions, the bedrock shield has in many places been overlaid by sediments to later be deformed, subjected to metamorphosis and folded and raised like mountains. In North and East Greenland, sediments continued to be deposited in the Palaeozoic geological era (from 541 to 252 million years ago) and were then subjected to the mountain range formation that formed the Caledonian fold belt in East Greenland and the Ellesmerian fold belt in North Greenland. Later, large sedimentary basins in West Greenland were filled with deposits from the Cretaceous more than 60 million years ago, and in connection with the Tertiary opening of the North Atlantic, large parts of South Greenland were exposed to extensive volcanic activity.

The geology of Greenland contains a number of important mineral deposits of e.g. coal, lead, zinc and cryolite, which have previously been exploited commercially. The earliest mining is known from the Stone Age, when the Saqqaq culture utilised a special deposit of killiaq (a very hard slate) as their preferred material. However, most mineral deposits are difficult to access, making mining unprofitable in most cases, but in recent years, repeated attempts have been made to extract e.g. gold, platinum, uranium. Maarmorilik and Mestersvig are new mines used for large-scale extraction, and they have had major local impact and in both cases caused considerable pollution.

The continental shelf around Greenland is a geological continuation of the land areas. The subsoil is dominated by a crystalline bedrock, which is covered by younger sediments and basalts. On deeper water, these deposits are replaced by actual ocean floor rocks consisting of material formed in connection with the seabed dispersal.

Most of the ice-free part of the country is below the height of 1,500 m. The highest point, however is Gunnbjørn Fjeld (about 3,700 m), the highest mountain north of the Arctic Circle. It is located on the east coast near Tasiilaq and is a nunatak, which is a mountain top or rock that reaches through glaciers or the ice sheet. In several places, glaciers from the ice sheet reach all the way to the ocean, meaning that the ice-free part of the country consists of at least three non-contiguous land areas separated by glacial ice. This has had an impact on the spread of e.g., caribou and muskoxen. Likewise, nunataks may have served as refuge for animals and plants during the glacial periods and thus had a decisive impact on the spread of biological diversity since the last glacial period.

The topography of Greenland includes high mountains along the coasts, while large parts of the icecovered area are below sea level. The northernmost part of the country, Peary Land, is not covered by an ice cap because the air is too dry to produce enough snow.

From north to south, Greenland can be divided into several climate zones, vegetation types, etc. The differences are decisive for the living conditions – not least the length of summer, which is relevant for the presence of permafrost, and the mean temperature in summer, which is decisive for agriculture and tree growth. Add to that the water balance, which to the south is dominated by a precipitation surplus and thus leaching of nutrients and salts. To the north, precipitation is so low that it is in fact an Arctic desert, where salts precipitate on top of the earth. Everywhere, plants and animals can be found that have adapted to the natural conditions and made it possible for humans to follow.

In many places, the coast is characterised by deep fjords, high mountains and an archipelago filled with islets and reefs. The coastline is more than 44,000 km measured on maps in the scale of 1:250,000. However, the length of the coastline depends on which scale is used. In satellite images with a resolution of 0.5 m, the Danish Agency for Data Supply and Infrastructure has found a coastline of approximately 105,000 km. All towns and settlements are located along the ice-free coast, and the population is concentrated along the west coast. The northeastern part of the country constitutes the world’s largest national park, the National Park in North and East Greenland, covering an area of 1 million km2.

Further reading

- Agriculture in Greenland

- Biodiversity and nature management

- The climate in Greenland

- Coasts

- Geology in Greenland

- The fresh waters

- The ice sheet

- The ice-free landscapes

History

The Greenlandic name for Greenland, Kalaallit Nunaat, means ‘land of the Greenlanders’. The first word, Kalaallit, is in all likelihood derived from a European term for Inuit in Greenland.

In Greenlandic parlance, Kalaallit was widely used in Southwest Greenland during the 19th century, whereas in Northwest Greenland Inuit was used for longer. Later, Kalaallit became the common national self-designation. Thus, the country’s name has references to the Inuit culture, the encounter with Europeans, colonisation, and the formation of the nation in recent times.

The country’s earliest history begins well over 4,500 years ago with a migration from the areas we know today as Siberia, Alaska and Arctic Canada. The first people in the country are seen to be directly connected to people in Arctic Canada, and it appears they have inhabited large parts of the Greenland coast.

Since then, the last migrating Vikings came from Iceland and settled as farmers in Southwest Greenland. This is when the country was given the name that is still used in Danish – Greenland.

CHRISTIAN VIBE/RITZAU SCANPIX, 1936

At the end of the 12th century, when people came to the country again, they came from the west, once again as a result of a migration. Over the course of just a few generations, the migration led Inuit from Alaska across Canada and eventually into a country where the Norse were about to give up their existence as farmers. The newly arrived Inuit laid the foundation for today’s Inuit population, the Kalaallit. They encountered Europeans regularly who hunted whales along the coast, and from 1721 the European presence became permanent.

The Danish-Norwegian kingdom began to take an interest in the country the Norse had left, but which in the Nordic consciousness was still part of the kingdom. Therefore, the Danish king supported the project which the missionary Hans Egede wanted to establish with Norwegian traders, and a few years later, the king also showed goodwill towards the Moravian Brethren Congregation, which was to support the work of Hans Egede.

This began an actual colonisation with Christian missions and trade, and alongside the construction of trading posts along the west coast from Nanortalik in the south to Upernavik in the north, the life and culture of the Inuit were drastically changed. The colony project depended on the Inuit hunting and experience as the blubber, the primary trade product, came from Kalaallit seal and coastal whale hunting.

With the establishment of the state-owned Royal Greenland Trading Department (KGH) in 1774, the Danish state took over the colonisation entirely; the KGH was the actual colonial administration until the early 1900s, when trade and administration were separated.

Inuit hunting had been free before – it had to feed the family and the settlement. Now it became an integral part of a trading economy, which had to be borne by the selling of whale oil and seal skins on the world market. In the late 19th century, when blubber lost its importance as a commodity, the focus turned on reforms of industry and societal structure designed to make the economy of the colony self-sustaining again.

Many of the changes were of great importance both culturally and economically. In the early 1900s, colonial rule decided that fishing should bear the economic development, and so sealers had to change professions. This brought about a drastic cultural and economic change that was reinforced with the modernisation reforms after World War II.

The hunting profession remained central to the Inuit culture, but the modernisation that followed the post-war new arrangement had, for the first time in colonial times, been entirely based on a Danish role model, both culturally, linguistically, administratively and politically. At the same time, modernisation brought about the largest ever addition of Danish labour – in construction, education and administration, increasing the impact Denmark had on social development.

Everywhere in daily life at workplaces, schools, and in the social and health care system, the population saw this development as a new colonisation. It brought improvements in living conditions in a number of areas, but it also brought frustrations which, over time led to a mobilisation of political resistance, which became fundamental to the demand for increased secession from Denmark.

Although the colonial era formally ended with the new arrangement in 1953, the country did not achieve the political equality with Denmark that was expected. The home rule implemented after the referendum in 1979 was the first step on the road to a more independent country and the building of a society on the population’s own terms.

In 2009, that development continued when self-government was introduced. This happened after a referendum in which there was a large majority in favour of Greenland as an autonomous country in the Unity of the Realm with Denmark and the Faroe Islands.

Further reading

- Paleo-Inuit

- The Norse

- The Inuit culture, precolonial period

- The colonial period until the war years

- The war years and subsequent decolonisation

- Home Rule (1979‑2008)

- Namminersornerullutik oqartussat (1979-2008)

Culture

TUSASS, 2021

The ancient myths, nature, history and traditions play a key role for Greenlandic culture. Since the Greenlandisation of the 1970s, there has been a growing interest in reviving traditional cultural expressions, which were disappearing, and at the same time there has been a keen interest in strengthening the existing culture. However, some artists are turning their eyes more to global challenges and international currents.

The traditional drum dance and song are now seeing renewed interest. In 2021, the tradition was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Music has generally been of great importance for Greenlandisation, including the rock band Sume, who sang in Greenlandic in the 1970s on topics dealing with Greenlandic themes and at the same time had a critical perspective on the overly dominant Western influence on development.

Another example of retention of traditions is the hunting culture. Life as hunters is closely related to identity, community and cultural rules that help maintain the balance between man and nature. Although occupational hunting today has limited importance to the overall economy, it is still considered an integral part of the culture.

While new materials and architectural trends have been adopted buildings, they are still being adapted to culture, nature and the climate challenges.

Among the earliest visual artists is Aron from Kangeq, who in the mid-19th century depicted Greenlandic legends and myths in watercolours. In 1972, the first art education, Grafisk Værksted (Graphic Workshop), opened. In newer visual arts, a movement is seen away from the national narrative, and the artist now tend to address colonial and post-colonial issues.

The same trend is seen in fashion and design: Where previously, mainly products that referenced Greenlandic culture were created, the gaze is now turned to more global trends – while using the symbols of the Inuit.

The oral storytelling has been an important element of social life, and from the 19th century many of the tales were written down. Where literature in the past most often contributed to the love of Greenland and national consciousness, a new development emerged in the early 2000s, addressing different themes and breaking down taboos.

Cultural dissemination has played an increasingly larger role, and by the end of the 1900s there were cultural history museums in most Greenlandic main towns. Nunatta Katersugaasivia Allagaateqarfialu, the Greenland National Museum & Archives, established in 1966, is the largest in the country. In 1995, Greenland’s first art museum opened in Ilulissat, and in Nuuk, it has been possible to visit the Nuuk Art Museum since 2005. In addition, most main towns have settlement halls or cultural centres; in 1997, the Katuaq cultural centre opened in Nuuk.

Further reading

- Association activities and volunteering

- Building customs and architecture

- Fashion and design

- Film in Greenland

- Food culture

- Inuit hunting culture

- Language

- Literature

- The media in Greenland

- Museums of cultural history and heritage

- Music

- Religion and religious communities

- Theatre and dance

- Traditions and tales

- Visual arts and crafts

Society and business

AQQALU AUGUSTUSSEN/KIVITSISA, 2020

What and who sets the framework for developing the individual, businesses and society in Greenland? The overall framework is set by the Danish Realm, the Government of Greenland and, not least, by the global trends in the political and economic markets.

Basically, the social structure and political system as well as administrative structures in Greenland are based on Scandinavian/Danish norms and ways of organising. The significant differences lie in the fact that it is a completely different country with a completely different people and a culture that was beyond comparison with the Scandinavian or Danish ones. In addition, the population is only about 56,000, which is of course a limitation in itself, not least in a very extensive country of about 2.2 million km2 with a scattered settlement pattern which impedes all public efforts.

In essence, Greenlandic communities are operationally so-called insular communities where it is necessary that all societal functions, such as electricity supply, school, healthcare, shop, etc., be found in all communities, almost no matter how small they may be.

The question is often: What could the Greenland society be compared to? Most often, it is compared with the Danish society, regardless of the aforementioned fundamental differences. In short, the living conditions and many other societal conditions in Greenland are not comparable to those in Danish society.

GEORG JENSEN/ARKTISK INSTITUT, 1963‑65

Greenland is more comparable to all current and former colonies of Western countries – and, of course, not least comparable to other Arctic, isolated and small communities. In all colonised societies, from north to south and from west to east, people grapple with the same social, personal and economic problems. There are approximately 375 million people on the globe who identify themselves as indigenous peoples. These are most often people who have been split up into different states and island communities when borders were drawn between the states. What characterises these communities is that they exercise self-determination to varying degrees, but the colonising state still has jurisdiction over crucial matters.

A number of publicly owned infrastructure companies, such as Tusass (formerly Tele Post Greenland), Air Greenland, Arctic Umiaq Line, Royal Arctic Line, KNR (Greenland Radio), town buses and privately owned taxis and broadcasters provide a physical and digital infrastructure that is accessible to the vast majority of places.

Climate change is the cause of much of the renewed attention on Greenland and the rest of the Arctic. In the new world order Greenland has again been brought into play against old and new enemies in the world for the United States. During COP26 in Glasgow on November 1st 2021, Premier Múte B. Egede stated that Greenland will join the Paris Agreement, which was adopted at COP21 in 2015. Greenland is thus positioning itself as a climate-friendly country where oil and gas exploration has stopped. Critics believe it will cut off the country from foreign and much needed investment, while Naalakkersuisut is confident that a green profile for Greenland is more alluring to potential foreign investors. Renewable energy sources, such as wind and hydropower and the sun, are seen as great potentials for the country’s own supply of energy, but also as a basis for stored energy and as a supply to energy-intensive industry.

The Danish State and its institutions in Greenland perform a number of civil and military functions. In addition to the legal system and the upper courts, this includes the enforcement of the borders of the kingdom and the fisheries inspection, as well as 31 other more or less essential responsibilities.

Lack of education remains a crucial Achilles heel for the development of society. Regardless of steady progress, there is widespread criticism of the results at virtually every level of the education system. In primary school, both the children and teachers grapple with problems that relate more to life outside school than actual schooling. In the institutions of higher education and in the trades, the dropout rate of students and pupils is high. There is also free admission to Danish educational institutions, and students can obtain Greenlandic educational aid if they take courses deemed eligible by the Self-Government, or they can choose to get SU (Danish state education grant).

The low degree of formal education, and perhaps, as a result, also the low level of attention to international relations, shape the public debate and thus also set part of the political agenda. At the same time, it makes it necessary to call in a relatively large number of formally trained workers from outside. Recent statistics show that in 2019, young people ‘outside the system’ in the ‘youth target group’ (16 to 25-year-olds) amounted to just over 3,000 persons. That is young people who are not in education or employment.

Further reading

- Education

- Health and care

- Housing

- Industry and labour market

- Infrastructure

- Plans in Greenland

- Population and demographics

- Self-Government

- The Unity of the Realm and the Danish State

Municipalities and towns

ANINGAAQ R. CARLSEN/VISIT GREENLAND, 2021

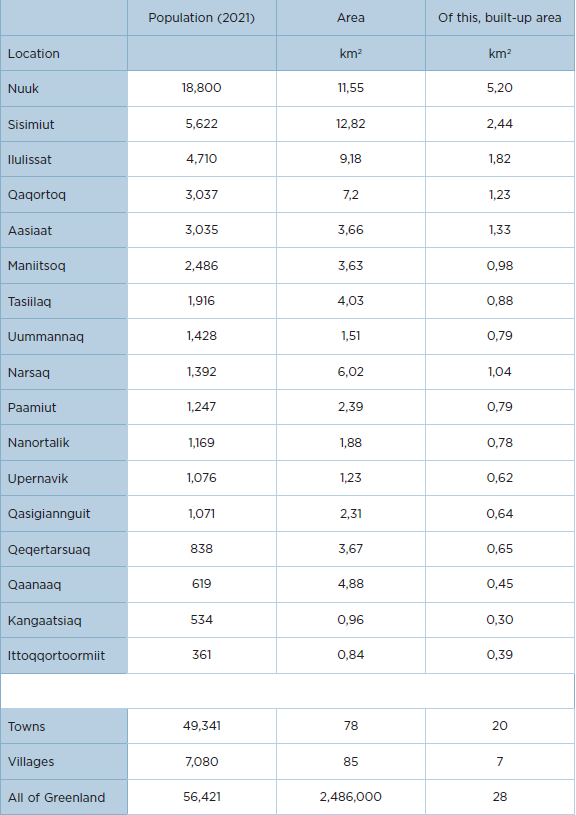

Greenland is the largest island in the world. Much of the country is made up of ice or tundra, and the Arctic climate is not always well disposed to settlement. There are only a few and relatively small towns and settlements scattered like stamps along the coasts. With a population of 56,421 (1 January 2021) and a total area of 2,486,000 km², most of the country is uninhabited, with population density being the world’s lowest. The population density is 0.14 per km², and if the ice sheet is included, then the figure is as low as 0.025 inhabitants per km².

In a historical perspective, the Inuit settled where the hunting opportunities were – depending on the time of year – and where there was a natural harbour and protection from the harsh climate. In areas of solid ice during winter, access to hunting on the ice was essential. The Inuit returned to the best hunting grounds, and they often became of a more permanent nature. Many of Greenland’s towns and settlements are founded on the former hunting grounds of the Inuit, some at whale stations set up by foreign whalers, and others where missionaries or government planners saw it fit. Finally, it may be a combination of the above.

Here, the main focus is on the towns where most of the population lives. Only 12‑13 % of the population live in settlements and sheep farms and a small proportion in stations in open land. The latter typically has research, technical infrastructure or sovereignty enforcement as its purpose.

ANINGAAQ R. CARLSEN/VISIT GREENLAND, 2021

On or along the ice sheet, there are a handful of research stations, e.g. Summit at the top of the ice sheet. It is run by American researchers in collaboration with Greenlandic, Danish and international researchers. Another type of station is the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol’s headquarters in Daneborg, Northeast Greenland, whose main purpose is to enforce the sovereignty of the Unity of the Realm in the National Park. Danmarkshavn, originally founded by the Denmark Expedition in 1906, in the middle of the National Park in Northeast Greenland, is a station with a gripping history, and the station is still permanently staffed by six people and used by scientists, technicians and occasionally by the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol. Since 1948, it has served as a weather station, and the long data time series are invaluable for international aviation and for research – including in climate change.

Tussas (formerly Tele Post Greenland) operates numerous of radio chain stations which form the backbone of communications infrastructure. Today, the majority are unmanned.

The individual towns and settlements – and virtually all other settlements – are to be seen as isolated insular communities with a defined infrastructure and supply lines and dictated by geography and climate, especially the long, dark and cold winter.

Over the winter, many of the northern towns and settlements have solid sea ice. When the ice is safe, transportation often takes place by dog sled, snowmobile and even cars across the ice. The purpose is hunting and fishing from the ice or transporting goods and persons between the settled locations. Longer journeys and all imports and exports of goods are either paused or by air and helicopter during the period when the solid ice does not allow navigation. The further north, the longer the period when the settled locations are effectively shut down from the outside world. However, the period of solid ice which is safe for fishermen, hunters and people in general to travel on getting shorter due to climate change. That does not mean that the period of closure will be shortened.

Often the inhabitants of the towns and settlements instead have a long period of unsafe ice, which makes navigation and other transport difficult or impossible.

Sled dogs and dog sleds are associated with the solid ice in the winter and are found only north of the Arctic Circle as well as in the Ammassalik district on the east coast. This is simply for practical reasons, but is also secured by legislation to protect the particularly suitable and adapted sled dog from mixing with less reliable dog breeds.

Although Sisimiut is an open-water town, the town has an active sled dog culture with a large catchment area and sled tracks all the way to Kangerlussuaq. Nowadays, dogs are often harnessed to the sled to satisfy tourists and citizens who simply want the experience. Further north, the development is the same, but fishermen and hunters still use the sled as a means of transport to and from the hunting grounds. For long periods, the Ammassalik district is isolated behind the multiyear ice – ‘storis’ (great ice), but strong ocean currents often mean that the ice is not passable. Much of the dog sledding between Tasiilaq and some of the settlements in the districts therefore takes place over land.

A number of towns and settlements in southern Greenland do not have solid ice. The heat from the Gulf Stream is the primary factor and ensures that the towns on the west coast from Nanortalik in the south to Sisimiut in the north are open-water towns throughout the year. Thus, the towns and associated settlements can be reached by boat year-round – in principle. The storis, which originates in the Arctic Sea and over summer drifts down the east coast, around Uummannarsuaq (Cape Farewell) and northwards on the west coast, gives rise to major problems with maritime accessibility, especially in South Greenland, but during periods also all the way up to Paamiut. Despite the storis (great ice), sea navigation does take place, but in certain seasons it is more the rule than the exception that delays occur, or that the storis simply packs up so much that for days the waters completely close to navigation.

The ice and climate are terms that Inuit live with and adapt to. The same applies to infrastructural challenges related to each settlement being an insular community. There are no roads and railways between the settled locations, and people and goods are transported by air or sea – by dinghy, boat or ship – in winter in North Greenland over the ice.

Each town or settlement must be self-sufficient with electricity, water, heating and telecommunications, waste and waste water management. If the power plant – or supply line from the hydroelectric plant – suffers a failure, there is nowhere else to get electricity from. For this reason, power outages are common. The corresponding situation applies to the supply of water, heat and telecommunications. There is no backup in the grid – because it does not exist.

Greenland has 17 towns and 56 settlements, two of which in the Uummannaq district have been closed since 2017 due to a tsunami triggered by a large mountain slide. The size of the towns varies from barely 400 inhabitants in the smallest, Ittoqqortoormiit, to about 19,000 in the capital, Nuuk. On an international scale, they are all small towns. Similarly, the population of the settlements varies from 475 in Kangerlussuaq to 14 in Kangerluk (as of 1 January 2022). This means that some settlements have more inhabitants than the smallest town, and the concept of a town is merely used for administrative purposes.

Until a local government reform in 2009, there were 18 municipalities in Greenland, and the settlements that were home to a municipal office were defined as a town, while the other settlements of the municipality were settlements. The municipalities took their name after the town, except for Ammassalik Municipality, where the town changed its name to Tasiilaq along the way. The old municipality towns have maintained their town status after the 2009 reform, and the former municipalities are today referred to as districts. The exception is Ivittuut Municipality, where the town of Ivittuut and later Kangilinnguit (the Grønnedal naval station) were vacated and the settlement of Arsuk came under Paamiut district.

Further reading