IVARS SILIS, 2021

RUBEN BLÆDEL, 2014

The word for art, eqqumiitsuliorneq, is first seen in 1871 in a dictionary by Samuel Kleinschmidt, where it translates to ‘one who often does uncommon things: an artist’. The word can be translated directly into making something remarkable or simply art.

The Greenlandic concept of art is first seen in the middle of the 19th century. Until then, traditionally, beautifully ornate objects were made, and the decoration itself has been entrusted with a function; it was believed that the decoration made the thing better and that a seal would rather be hunted by a beautiful harpoon than by an ugly harpoon.

From the middle of the 19th century, the functionless art appeared on the scene, and as the art community has grown stronger, the desire and need for art institutions has also grown. From this time, there has been a tendency for Greenlandic artists to have had someone who has taken on some kind of mentoring role, including by sourcing outside materials and buying up the artist’s works. Before 1970, the artists were predominantly male, but then a shift occurred and today, the majority are female.

Visual arts

Today, there are small municipal art museums in Nuuk and Ilulissat. Both are based on former private collections, are created on private initiative and are today run by the municipality. Greenlandic artists also frequently exhibit their works in Greenland’s cultural centre Katuaq in Nuuk, in the cultural centre Taseralik in Sisimiut, in local museums and in some companies offering the opportunity to make exhibit in their premises.

Exhibitions outside Greenland are usually in Denmark at institutions that primarily work with Greenland and not with art, for example in De Grønlandske Huse (the Greenlandic Houses) in Denmark. It is a challenge that art is viewed from a Greenlandic perspective and efforts are being made to create a national art museum.

Art in Greenland has always been and still is such a small field that it is borne by quite a few people both at the institutional level and at the artist level. The art very much relies on people and is therefore difficult to put into periods and trends. Today, the Greenlandic art world is made up of just over 25 professional artists, and this is probably the largest number ever.

Early visual arts – anthropological collection

In the transition from functional decoration to functionless art, the concept of eqqumiitsuliorneq arose, and in this early phase, art consisted primarily of drawings, watercolours and prints. One of the first visual artists was Aalut Kangermiu, Aron from Kangeq. His works include watercolour, wood carving and drawing, but also written texts. Aalut Kangermiu was a catechist of the Moravian community in Kangeq and could both read and write Greenlandic, and then he was a hunter. He fell ill with tuberculosis, and during one of the periods when he was bed-bound, the Greenland explorer and civil servant H. Rink requested Aalut to write down Greenland legends, myths and ways of life and ‘Especially, moreover, anything that could serve as amusement or entertainment for Greenlanders’ as stated in the announcement that H. Rink sent out to all of West Greenland in 1858. The request included both writings and pictures.

The invitation testifies that the purpose was to gather knowledge for the Greenlanders themselves. Aalut’s works were therefore a kind of commissioned works with a defined purpose; the collection of local history was to help build a national identity.

Aalut Kangermiu shares history with, among others, Jakob Danielsen in North Greenland, who also created art from his bed, and in East Greenland, it was Kârale Andreassen who depicted everyday life, hunting, shamans’ journeys and myths. They all relied on good connections and materials from abroad, and none of them were trained in the art profession. The works were not necessarily collected because of their artistic qualities, for example very naive drawings by Andreassen were collected from when he was only 13 years old. The works thus lie in a field of tension between anthropological collections and art. No women were registered in visual arts until around the mid-1900s.

From landscape painting to abstraction

Aalut Kangermiu was followed by a growing number of artists, and in terms of materials, the works extended to include oil painting on canvas. It was still primarily catechists, priests, teachers and other relatively well-off Greenlanders who created the pictures. Nature was the predominant motif, and this genre includes Steffen Møller, Peter Rosing and Niels Lynge. It continued to be mainly men trained and employed in professions other than art.

After this time, when nature painting took centre stage, a transitional period followed characterised by larger abstractions and more impressionistic art. There was more experimentation with the motifs, and the first female artists began to establish their presence. In Kîstat Lund’s landscapes, the goal is no longer to reproduce the seen or to create a tale; the works stand as an interpretation of moods and play with colours. Another significant profile from this period is Thue Christiansen, who is known as the artist behind Erfalasorput, the Greenlandic flag.

Only in the latter half of the 1900s did artists begin to educate themselves in the field. There was no such thing as actual academic education, but more and more were taking courses, including at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, including sculptor Simon Kristoffersen, who in the years around 1967 had a short stay at the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and was awarded the Academy’s silver medal for outstanding artistic work.

Danish artist Bodil Kaalund was in Greenland for the first time in 1968, and she came to serve as a lecturer and mentor to a number of Greenlandic artists, among others, she helped artists such as Hans Lynge, Aka Høegh and Anne-Birthe Hove make contact with art academies.

Kaalund has been behind a number of international exhibitions by Greenlandic artists and published the largest work to date on Greenlandic art in 1979. In addition, she co-initiated the establishment of Grafisk Værksted (Graphic Workshop) in Nuuk, and she was active in the work surrounding the founding of a national art museum.

The Art School and institutionalisation of art

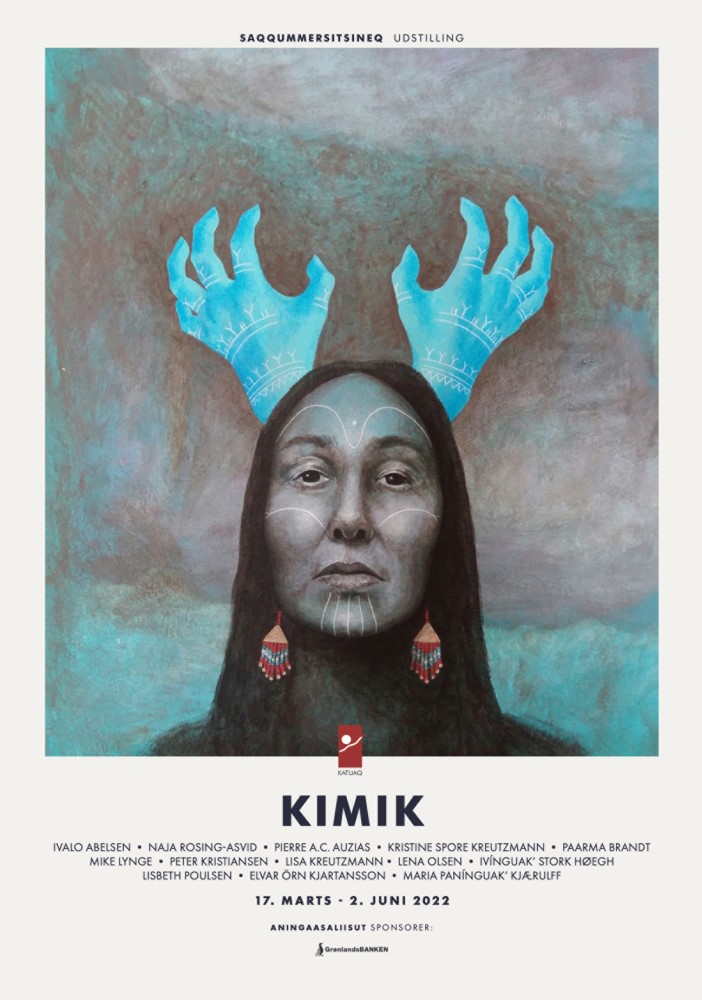

KIMIK, ASSOCIATION OF ARTISTS IN GREENLAND, 2022

The first Greenlandic art education, Graphic Værksted (Graphic Workshop), opened in 1972. The school, today called Eqqumiitsuliornermik Ilinniarfik, Greenland Art School, was initiated by Hans Lynge and Bodil Kaalund. They argued that a graphic workshop was a natural further development of the tradition of carving and incising scenes. The goal was the same as in the time of Aron from Kangeq, namely to create works that came out to the people and were of use in society. There was a clear desire to be inspired by traditional Inuit culture and thereby create a visible Greenlandic identity in art.

Since then, almost all Greenlandic artists have been students and often also teachers at the school. One of the first and most well-known people is the artist Aka Høegh. From her childhood, she dreamed of becoming an artist, but the Home Rule refused to let her study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, but without being enrolled, Høegh managed to follow the courses for a number of years. In the following years, it became significantly easier for young artists to graduate abroad, and both Arnannguaq Høegh and Anne-Birthe Hove graduated from art academies. Both came to play a major role up through the 1980s and 1990s, becoming the start of a sustained wave of academic-trained artists, the majority of whom remain women.

The field grew with artists such as Buuti Pedersen and Miki Jacobsen, who in 1995 were co-founders of KIMIK, the Association of Artists in Greenland. They helped to ensure that the Greenlandic artists had a mouthpiece. They were negotiated for annual spring exhibitions, and together could apply for funds for major joint projects. It also resulted in a number of releases, including Grønlandske nutidskunstnere (Greenlandic contemporary artists) by Camilla Augustinus from 2004 and KiMIK’s own 2015 anniversary book, as well as a series of exhibition catalogues for exhibitions outside Greenland, e.g. The Red Snowmobile, a joint exhibition held at The North Atlantic House in Copenhagen in 2005.

Debate-provoking art and art after the introduction of home rule

FOTOKOLLAGE AF INUK SILIS HØEGH/MELTING BARRICADES, 2004

Danish-Greenlandic artist Pia Arke graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen in 1992. Her graduation project, the essay Ethno- Aesthetics, outlines the expectations for art when it is perceived as ethnic and Greenlandic. Arke here questions what makes art Greenlandic. Should you be able to tell from the motif that it is Greenlandic, and if so, what would that say?

An artist like Frederik ‘Kunngi’ Kristensen, who created non-figurative works, often saw his works being rejected because they were not Greenlandic enough. Should art in Greenland have a local connectedness to have a local relevance, or can it be global and yet native to Greenland?

A lot of art continues to be created with Greenlandic motifs, but it seems more like an inspiration drawn from the everyday life of the artist rather than a desire to create something that underpins a national narrative.

The motifs may be, for example, block of flats, myths or nature, but the works may as well deal with current plans for mines at Kuannersuit – Kvanefjeld in Narsaq, as seen for example in the works of Bolatta Silis-Høegh and Ivínguak’ Stork Høegh. The colonial past also plays a large role in, for example, the works of Julie Edel Hardenberg. This is seen in her work Rigsfællesskabspause (Unity of the Realm Pause), a straitjacket created from the Danish and Greenlandic flags.

Since 1990, a number of artists have worked with conceptual art, such as installations, interventions, performance and video art. Specifically, Jessie Kleemann has created some attention-grabbing performative works. Together with Danish artist Asmund Havsteen-Mikkelsen, Inuk Silis Høegh created the Melting Barricades project, a major performance project that toyed with the idea of creating of a Greenlandic military. The project involved personnel carriers, uniforms and recruitment in the streets of Nuuk and Copenhagen.

Crafts

Two main trends are seen in Greenlandic crafts: one that is closely related to the visual arts, and one that leans towards applied art.

In the first and more recent trend, you will often find artisans who create both visual arts and crafts. Many are members of the Association of Arists in Greenland, KIMIK, e.g. Buuti Pedersen, graduated from the School of Decorative Art, today the School of Design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. In addition to the visual arts, she has created a number of glass sculptures, decorations with baptismal fonts, jewellery series, etc. Another example is Kristine Spore Kreutzmann, graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts’ Glass and Ceramics School at the island of Bornholm. Kreutzmann makes both experimental ceramic works and cups and dishes for the home. Maria Panínguak’ Kjærulff works in the field of tension between design and visual art. Her series Inuit Lady, a series of watercolours and prints, depicts small ulus (knives) that have been turned into women with kamiks, mittens with orchids and other decoration. The series stands out from her otherwise large and expressive works, and it has become a standalone design line with a very different expression from her other works.

The part of the handicraft that lean more towards applied art includes figurines, jewellery and the like, often made of bone, stone and tusk. The only place in Greenland to train in this field is Kalaallisuuliornermik Ilinniarfik, the School of National Clothing Education in Sisimiut, which works to create the Greenlandic regional costumes.

Simon Kristoffersen is one of the people who have historically had a great importance, especially for the soapstone figurines. Father and daughter Aron Kleist and Cecilie Kleist have established a presence in the field of bone carving work, and artists still refer to their works.

Today, especially Kristian Fly, Kim Eriksen and Oline Binzer are worth noting. All of them create polar bear heads for quick sale, but at the same time immerse themselves in largescale experimental unique works.

Tupilak

MADS PIHL/VISIT GREENLAND, 2013

The tupilak, a small figure carved in bone or tusk, is one of best known Greenlandic artistic expressions, but it is quite a new thing.

The word ‘tupilak’ originally denotes the evil spirit you could cast on a person who you would like to harm. The spirit has been illustrated by Kârale Andreassen. It was not until around the year 1900 that figures depicting the spirit began to be created, and these are the figures we know today as tupilak: grotesque figures carved in the bone and tusk that often also incorporate a number of animal elements. Very few of the artists are named, and the figures are often stated as works by an unknown artist.

There are a number of references to the figure among Greenlandic visual artists, for example Anne-Birthe Hove, who in her work Portrait creates a figure-like creature in the same way as a tupilak.

A number of attempts have been made to provide supplementary training in and raise the quality of this type of handicraft, but none of the initiatives have been successful.

Further reading

- Building customs and architecture

- Fashion and design

- Four tales illustrated by Aron of Kangeq

- Greenland painters

- Hans Lynge and Jens Rosing

- Inuit way of life

- Museums of cultural history and heritage

- Religion and religious communities

- Traditions and tales

Read more about Culture in Greenland