MADS CLAUS RASMUSSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

The formal connection between Greenland and Denmark came about when in 1380 Denmark and Norway formed a union. That was the starting point when, from 1721, Danes and Norwegians resumed colonisation. When Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden in 1814 after the Napoleonic Wars, trade and administration of Greenland and the Faroe Islands were transferred to Copenhagen.

After World War II, the Danish government asked one of the country’s most prominent jurists, Professor Alf Ross, to assess the changes planned with regard to the position of Greenland and the Faroe Islands. He took the opportunity to describe the concept of the ‘Community of the Realm’ as legally meaningless, because a ‘community’ requires the parties to have equal status. Ross therefore believed that the term ‘unity of the realm’ better described the relationship. Nevertheless, in daily practice, the concept of the ‘Community of the Realm’ forms the framework for relations between Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands – and for the discussions on what the relationship should be like.

The constitutional status of Greenland and the Faroe Islands has been contested in separate ways as a result of widely differing history in terms of belonging to Denmark. The Faroese have insisted on describing themselves as a separate nation that has never accepted the transfer of sovereignty to Copenhagen. Greenlandic criticism has been focused on whether the formal integration of Greenland in 1953 was based on a free and informed consent that lived up to United Nations’ standards for decolonisation. The objections have pointed in particular to the fact that Greenlanders were not presented with UN alternatives to integration: independence and free association.

Politically, the Unity of the Realm is often referred to as equal, but the official Danish interpretation remains that the home rule and self-government arrangements in the Faroe Islands and Greenland, respectively, act as regional authorities that have been handed over power from the state. It is generally agreed that it will be politically impossible for Denmark to unilaterally abolish the arrangements. Some independent jurists believe that the arrangements have been given constitutional status, even though they are not mentioned in the Danish Constitutional Act, and that they are protected by the fact that under international law the Greenlanders constitute a people with the right to self-determination. Equality therefore consists of a right to independence, although it is manifested differently. Since the Self-Government Act of 2009 describes a procedure for how Greenland declares its independence, discussions have since concentrated on foreign and security policy, where equality is interpreted differently in Greenland and Denmark.

Greenland’s self-government is far-reaching in comparison with the overseas territories of other states. Self-government covers the vast majority of internal affairs and can be extended to virtually all other areas, even those traditionally considered core tasks of a state, such as police, legal system, foreigners and border control. The only thing maintained by the Danish State is that the constitution, citizenship, Supreme Court, foreign policy, security policy, defence policy and monetary policy should remain under Copenhagen as a prerequisite for being able to speak of a unitary state. The official Danish response to demands for increased self-determination in these areas has usually been that it would be in breach of the Danish Constitutional Act. However, the interpretation of the Danish Constitutional Act has changed over time, most spectacularly when, after all, it proved to be possible to take over mineral resources and, in principle, the police and legal system. The same movement has unfolded in relation to the involvement of Greenland and the Faroe Islands in foreign affairs. For some observers, the development underlines that interpretation of the Danish Constitutional Act in relation to the Unity of the Realm is the result of a political rather than a purely legal process.

Greenland and the Danish Royal House

According to the Danish Constitutional Act, the Danish Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy. The monarch is the head of state for all parts of the kingdom, including for Greenland and the Faroe Islands. Where the relationship with Denmark and the Danish state is a controversial subject, then generally in Greenland there is great devotion and respect towards the Danish royal family.

From the beginning of the colonisation, knowledge of the Crown became widespread in Greenland, both through the posted missionaries and merchants and through oral accounts from Greenlanders such as Pooq, who had visited the royal family in Denmark. The notions of the distant king were arguably obscure: Was he the powerful, wealthy and punishing master or the loving, protective family father? The king played an important role as head of the Lutheran Christian Church, and the Greenlandic congregations have since then prayed for the king and royal house at church services.

As the first regent, King Christian X visited Greenland with his family in 1921. For most Greenlanders, it was the first meeting with royalty of flesh and blood. Later royal visits with accompanying kaffemik and celebrations have helped build emotional bonds and more personal relationships between Greenlanders and the royal house.

The close ties are strengthened by intertwining the formal and the emotional, e.g. in the following ways: Queen Margrethe II herself presented the Greenland Home Rule Act in 1979 and the Self-Government Act in 2009 at ceremonies in Greenland. Greenland shows its recognition of the monarch and royal house through official flag-flying days where royal birthdays are celebrated. The members of the royal house are depicted on Greenlandic stamps, often wearing Greenlandic national costumes. In 2000, the Home Rule decided to name a remote area in northernmost Greenland after the crown prince, Kronprins Frederiks Land. It can be seen as a gesture of appreciation for the crown prince’s appropriation of Greenlandic culture when, in 2000, during his fourmonth dog sled journey, he travelled 2,800 km in northernmost Greenland. Accompanied by former members of the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol and with the assistance of hunters from Qaanaaq, he travelled from Qaanaaq to Daneborg. The crown prince’s twins were given the Greenlandic baptismal names Ivalo and Minik in 2011. By many Greenlanders, it was considered conciliatory and significant when in 2015, the royal couple went to Qullissat with the Royal Yacht Dannebrog to see with their own eyes the town which was closed by the authorities in 1972. Queen Margrethe II, in her televised New Year’s speeches, has continued and developed her father’s tradition of sending warm and acknowledging greetings to Greenland. From the first New Year’s speech in 1972, the Queen’s greetings were addressed to ‘the people of Greenland’ several decades before the Self-Government Act’s official recognition of the Greenlanders as a people.

The Greenlandic members of the Danish Folketing

PHILIP DAVALI/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

Since the amendment of the Danish Constitutional Act in 1953, Greenlandic voters, interests and views have been directly represented with two members in the Danish Folketing. Siumut has more or less held one of the Greenlandic mandates since the party was created in 1977. The second mandate was held by Atassut until 2001, when IA took over. As opposed to the Faroese members of the Danish Folketing, more than twenty years passed from when Greenland had its own representation until a Greenlandic member joined a Danish party (Lars Emil Johansen became a member of SF – the Socialist People’s Party – in 1975). After this, Greenlandic members have most often belonged or cooperated more loosely with Danish parties, most continuously Siumut and the Danish Social Democrats. From 2001 to 2011, the members of the Danish Folketing from Siumut and IA, formed a North Atlantic party together with the Faroese Republican.

The Greenlandic members of the Danish Parliament have mostly dealt with political issues which have been particularly relevant to Greenland. In particular, they have used the Folketing’s question time and committee work to check the Danish government’s administration of policy areas still under Danish jurisdiction. As members of the Danish Parliament, Greenlandic politicians have also had the opportunity to influence Danish politics, not least in those cases where they have been instrumental in building a parliamentary majority: After the 1971 elections, Moses Olsen and Knud Hertling were decisive for forming a Social Democratic government. In 2007, for some time, it looked as if the Greenlandic members could become crucial to the centre-right government for getting enough votes in a case involving the possibility of asylum families to live outside asylum centres. In such situations, the reasonableness of Greenland mandates being included on an equal footing has been contested. In recent years, Greenlandic politicians have been part of spending agreements on several occasions, although their mandates have not been necessary for a majority, for example in connection with the defence agreement and in connection with the establishment of a pool of funds for North Atlantic projects on the Budget.

Politics and administration of the Unity of the Realm

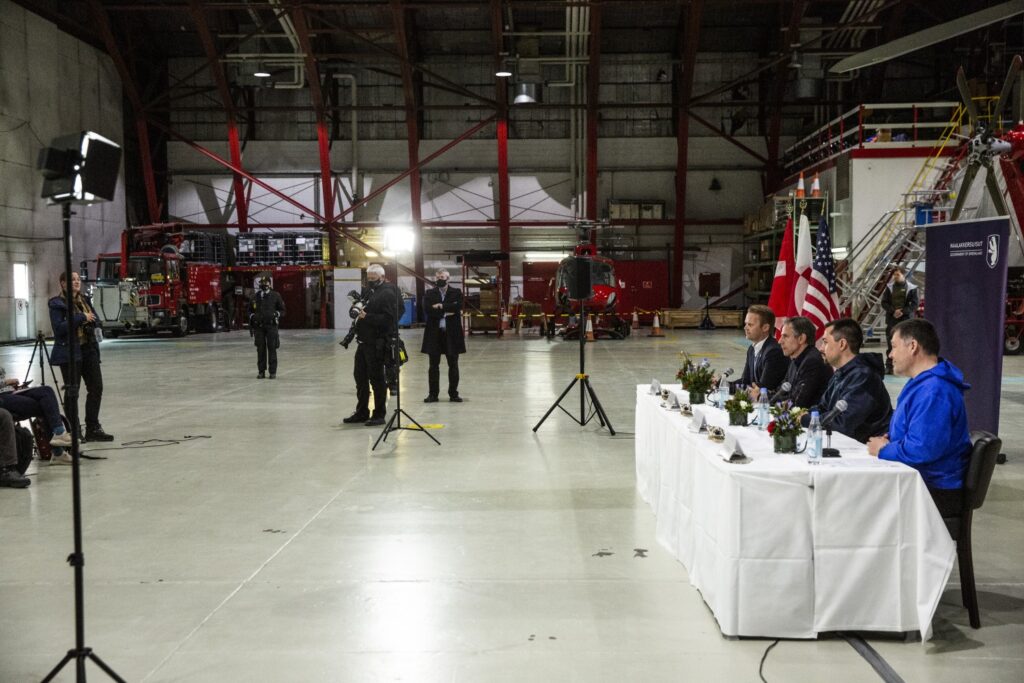

MADS CLAUS RASMUSSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

Politically and administratively, the Unity of the Realm is made up of a number of rules, institutions, practices and contacts between politicians and officials that tie Greenland and the Faroe Islands together with Denmark. At this more concrete level, the Unity of the Realm is not so much a triangle as two bilateral relations between Denmark and Greenland and Denmark and the Faroe Islands, respectively: The Danish Folketing has a Greenland Committee and a Faroe Island Committee. The Faroe Island home rule and the Greenland self-government might be similar, but they have been negotiated separately and at different times: Block grants are agreed and calculated in two separate processes, and different national legislation and international agreements may or may not be put into force with different adjustments for Greenland and the Faroe Islands, respectively. As far as Greenlanders and Faroese have coordinated, the contact has been mainly been undertaken by individual politicians. In addition to the Danish Parliament, the work of the Nordic Council and Council of Ministers, the Arctic Council, the Arctic Parliamentary Conference and especially the Western Nordic Council have helped to bring the parties together.

Since 1983, the so-called Summits of the Realm have been one of the few institutions to bring together the three political parties of the Unity of the Realm. Since 1995, the Prime Minister of the Faroe Islands and the Greenland Premier of Naalakkersuisut have, by turns, hosted biannual or annual meetings where the three top politicians speak together behind closed doors without officials. Often the venue has had a symbolic value, either nationally or for the host, and the meeting is surrounded by a short or long programme with spouses and sightseeing giving the impression of an official state visit. The nature of the meetings has alternated between family gatherings and strained arm wrestling about current issues.

The Summits of the Realm are prepared by officials. For a number of years, a regular series of meetings was formalised between the manager of the Greenland Home Rule and the Permanent Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Office, but due to the intensified flow of foreign and security policy matters in recent years, the series of meetings has been supplemented by ongoing contacts. In June 2021, a committee of ministers from all three parties to the Realm was established and the Prime Minister at the head of the table was established in an attempt to bring the foreign policy of the Unity of the Realm into unison. Both with regard to matters of state and cooperation in issues under Greenlandic jurisdiction, contact between ministries is most often on an ad hoc basis. A secretariat, a steering group or the like with representatives of both the Self-Government and the Danish authority is often formalised to facilitate concrete Danish efforts in devolved areas (e.g. social affairs).

The High Commissioner

The High Commissioner in Greenland, as the supreme representative of the Kingdom, is the heir to an office which has existed since 1782 under various designations and with changing tasks portfolio. Initially, the inspectors’ authority was primarily the administration and staff of the Royal Greenlandic Trading Company. From 1925, the two governors were chaired each their provincial councils in the North and South, supervisors of district councils and municipalities and at the same time heads of the administration of justice. After 1950, the Governor of Greenland was the bailiff for the technical area, housing, family law, education, health and, until 1965, the police. At the same time, the Governor chaired the Provincial Council. However, from 1967, the Council elected their own chairman. From 1979 to 1992, the newly established Home Rule Government gradually took over most of the administrative areas.

Consequently, changing High Commissioners have undertaken increasingly diminished administration, but at the same time developed a new role as a link between the Government of Greenland and the national authorities. Specifically, this is realised by the fact that the High Commissioner:

- ensures communication between Danish authorities and Naalakkersuisut

- keeps the Prime Minister’s Office up to date on developments in Greenland through reporting

- is involved in the planning and carrying out of visits by members of the Royal House, the Folketing, the Government, etc.

- proposes candidates for royal distinctions

- ensures that parliamentary elections, as well as any referendums, determined by the Folketing, are held in Greenland and that it is possible to vote by post in Greenland for elections in Denmark, the Faroe Islands and to the European Parliament

- has national laws and other legal regulations valid for Greenland translated into Greenlandic and publishes them on its website.

In addition, the High Commissioner deals with a number of family law matters such as separation, divorce, adoption, determination of child and spousal support, name changes and custody agreements. Added to this are supervision of funds held in trust for legally incompetent persons, application for free legal representation, verification of public certificates for use in the legalisation process by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark and citizenship proceedings. The High Commissioner also settles complaints about registration in the national register.

Other government institutions

A number of government authorities have staff in Greenland to manage areas still under Danish jurisdiction:

Naviair, which provides air traffic management services over Greenland.

The Danish Meteorological Institute’s (DMI) weather service provides knowledge about weather, sea and ice conditions.

The Centre for Occupational Injuries, which administers the Workers’ Compensation Act in Greenland, is a centre under the Danish Labour Market Supplementary Pension and the Danish Labour Market Insurance.

The Working Environment Authority in Greenland is, as part of the Danish Working Environment Authority, a board under the Ministry of Employment and oversees the Greenlandic occupational health and safety legislation.

The Maritime Authority in Greenland, which is part of the Danish Maritime Authority under the Danish Ministry of Economic and Business Affairs, undertakes tasks relating to safety on board, safety at sea, ship registration, etc.

GEUS, the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, has had a small office at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources since 2013 and assists authorities and companies with advice and specialist knowledge on issues relating to mineral resources and climate.

Justice area

EMIL HELMS/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

The police, criminal services and courts, apart from the Supreme Court, are among the areas that Greenland can take over under the Self-Government Act. Despite independence being on the agenda of almost all Greenlandic parties, taking over the legal system has not received much attention. Although the Self-Government has appointed a minister as responsible for the justice area, the Danish Minister for Justice is the person in charge, and it is the Danish Parliament, which after consulting in Inatsisartut, adopts laws and amendments in this area. The Danish Minister for Justice is the person in charge of this area, and it is the Danish Folketing, which, after consulting in Inatsisartut (Parliament), adopts laws and amendments in this area.

Police

GRØNLANDS POLITI, 2021

The task of the police is to maintain security, peace and order. Greenland forms one police district under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Justice in Denmark. The police district is headed by the police commissioner, who must hold a Master’s Degree in Law.

The office of police commissioner is located in Nuuk along with the central administration of police and is organised into three pillars:

- The prosecution service.

- The executive pillar, which, in addition to internal tasks, is also responsible for citizen contact regarding the issue of various permits. In addition, the Police College organisationally falls under the executive pillar.

- The police pillar, which is in charge of the national emergency operations centre as well as the 18 police stations in police regions North and South.

The largest staff group of the police are resident police staff trained at the Nuuk Police College. This group, which at the end of 2020 included 88 employees, will be supplemented by dispatched or assisting police staff from Denmark. In addition to policing duties, police officers also appear in court as prosecutors on behalf of the prosecution service, just as the police carry out a variety of civilian duties, including issuing passports, driver’s licenses, motor registration and alienation and paternity cases. In the settlements, the police are represented by municipal police officers, who receive quite short training. By the end of 2020, the settlements had 59 municipal police officers.

Courts

The district court in most cases forms the first instance and consists of one district judge and two judges appointed by the municipal council. The district courts follow the municipal boundaries, except for the Qaasuitsoq District Court which cover the two northern municipalities: Avannaata Kommunia and Kommune Qeqertalik. The district judges are not attorneys at law, but they have completed special district judge training with a duration of two years and three months.

Prior to a major legal reform in 2008, there were no educational requirements for district judges, they were merely required to be of good character and meet the conditions of eligibility to the local council. After the reform, the district judges are employed in permanent positions. In order to strengthen the quality of the administration of justice, a legal court has been established, the Court of Greenland, that takes care of legally complicated cases as the first instance. It is also the Court of Greenland that is responsible for the guidance and training of the district judges. The High Court of Greenland is the court of second instance and exclusively an appeal court. The High Court consists of one judicial county judge and two lay judges appointed by Inatsisartut (Parliament). The defence in the district courts is in most cases conducted not by attorneys at law, but by authorised defence counsels who have undergone a defence counsel training. The office of defence counsel is a sideline occupation. In the legal courts, the Court of Greenland and the High Court of Greenland, attorneys at law appear as defence counsels.

Prison and probation service

The prison and probation service is responsible for the enforcement of the measures imposed by the courts: supervision, community service and imprisonment. The Prison and probation Service also administers people detained by the police and conducts pre-trial personal investigations. The Prison and probation service in Greenland has its own director in Nuuk, who reports to the Directorate of Prisons and Probations in Copenhagen.

Imprisonment takes place in socalled institutions of delinquency. The first penal institution was erected in Nuuk in 1967 and had room for 18 people. The main principle of the penal institution was that the convicts should maintain attachment to the surrounding community through employment in the town, they should be re-socialised and supported for a future existence free of crime.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the number of inmates increased to a level well above the other Nordic countries. Today, there is room for 154 inmates in Ilulissat, Aasiaat, Sisimiut, Nuuk, Qaqortoq and Tasiilaq. Despite the intention of openness and contact with society, the institutions of delinquency have evolved over the years into closed institutions, with few inmates noticing the principles of the open institution. In the institutions of delinquency, there are few opportunities for activity, and re-socialising offers are limited.

With the legal reform, semi-closed wards were introduced in all institutions of delinquency, and a closed institution was built in Nuuk which widely has the characteristics of a prison. Inaugurated in 2019, the new closed institution, will, among other things, house persons given an indeterminate sentence who had so far been sent to serve in the Institution of Herstedvester.

The Defence

IDA GULDBÆK ARENTSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2019

According to the Self-Government Act, defence policy belongs under Denmark and cannot be devolved to Greenland. Formally, the Danish Defence undertakes the military defence of Greenland. In effect, the task has since World War II been undertaken jointly by the United States and Denmark. The United States has significant military interests in Greenland, especially because the island lies on the shortest air route between North America and Russia and Asia.

The military presence of the United States has been linked to scandals several times, such as the forced relocation of the local inhabitants in connection with the expansion of the Thule Air Base in 1953 as well as the secret stationing of American nuclear weapons in Greenland during the first half of the Cold War. Since the end of the Cold War, US military interest in Greenland has been more limited, but the Thule Air Base, now the United States’ only military facility, forms part of the US missile defence and warning system and is thus an important part of the US nuclear deterrent.

Since the late 2010s, the United States has again shown a greater interest in Greenland. This is due to increasing American fears about the presence of China and Russia in the Arctic. The United States has therefore placed greater demands on Denmark’s military presence in Greenland.

The Danish Defence asserts the sovereignty of Denmark, monitors the territory and helps protect Greenland militarily as a complement to the US defence of the North American continent. In addition, the Defence serves as a coast guard, carrying out tasks of great importance to Greenlandic society, especially search and rescue service, fishery inspection, maritime pollution prevention, hydrographical surveys and other civil society support tasks. A large part of these tasks are solved together with other authorities, for example, the search and rescue task is carried out in cooperation with the Greenland Police and Naviair, while environmental monitoring tasks are solved in cooperation with the Self-Government.

The Danish Joint Arctic Command carries out the tasks of the Defence in Greenland and the Faroe Islands.

The Defence has established the Arctic Emergency Force, an organisational structure that makes it possible to use the resources of the entire Defence, Home Guard and Emergency Management Agency in the Arctic in disaster situations or for sovereignty enforcement.

Defence expenditure in Greenland and the Faroe Islands amounts to approximately DKK 1 billion, but in response to the new security policy situation and in particular the interpretation of it by the United States, Denmark has announced new investments in the Arctic, initially to monitor airspace and ship traffic. In 2019, Denmark and Greenland reached an agreement allowing the Defence to continue using the airport at Kangerlussuaq, regardless of whether the Self-Government moves civil traffic to new airports at the main towns.

The headquarters of the Joint Arctic Command in Nuuk houses DMI and Naviair staff in Greenland in order to be able to coordinate and share knowledge, particularly in the context of crisis and rescue situations, environmental monitoring and sovereignty enforcement. In addition, the Americans established a consulate in Nuuk in 2020, reflecting the renewed interest of the United States in Greenland. So far, the consulate has an office in one of the buildings of the Joint Arctic Command.

Joint Arctic Command

MADS PIHL/VISIT GREENLAND, 2016

Danish Defence’s tasks in Greenland and the Faroe Islands are handled by the Joint Arctic Command (JAC) with units provided by the Navy, the Air Force and the Special Operations Command in particular. JAC was created in 2012 by a merger of the Greenland Command and the Faroe Islands Command. The capabilities and personnel of the Danish Defence vary depending on the season, but on average around 250‑300 people are deployed in and around Greenland.

The Joint Arctic Command typically has the following capabilities:

- 6 dog sled teams under the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol

- 1 Challenger surveillance aircraft

- 2‑3 Thetis inspection ships with helicopter

- 2 Knud Rasmussen inspection vessels

- 2 land-based Air Greenland helicopters on standby

- Periodically a frigate.

The Joint Arctic Command has the following stations:

- Liaison element Thule with a liaison officer at Thule Air Base

- Station Kangerlussuaq in the civilian Kangerlussuaq Airport

- Station Daneborg in Northeast Greenland, base for the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol

- Station North in Northeast Greenland

- Station Mestersvig in Northeast Greenland

- Liaison element Faroe Islands in Tórshavn

- Station and patrol service in Greenland at Aalborg Airport

- Station Grønnedal in South Greenland.

Foreign and security policy

ÓLAFUR STEINAR RYE GESTSSON/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

JENS DRESLING/POLITIKEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2017

As regards foreign and security policy, the Unity of the Realm formalises a number of procedures for the involvement of Greenland and the Faroe Islands and how they can act independently. The framework is set in the Danish Constitutional Act and (by agreement between Greenland and Denmark) in the Self-Government Act as well as in various laws on interaction between government and parliament. Thus, according to the Self-Government Act, Greenland can ‘negotiate and conclude international law agreements’ with foreign states and international organisations ‘on behalf of the kingdom’ within cases involving ‘devolved policy areas’. However, if Denmark is directly involved or is a member state of the international organisation in question, or if both Greenland and the Faroe Islands are involved, the state takes over. In such cases and in other foreign affairs conducted by the Danish Government, a number of principles for the discussion and involvement of Greenland (and/or the Faroe Islands) have been established. Greenland has won this influence particularly through three episodes involving the EU, the US, and the recent great power attention to the Arctic:

When Greenland left the EC in 1985 and during the same period took over the fisheries policy, international negotiations on fishing quotas became a key task. However, the first diplomats of the Home Rule foreign affairs office and Greenland in Brussels purposefully interpreted the mandate of the Home Rule Act to cater to Greenland’s ‘special commercial interests’ as broadly as possible. Today, the EU’s relationship with Greenland is defined by three agreements, two of which are continuously renegotiated. These are the Greenland Treaty following Greenland’s exit from the EC in 1985 and fisheries and partnership agreements. As long as the EU is satisfied with the fisheries agreement, Greenland, as an ‘overseas country or territory’ (OCT), has duty-free access to the EU market. Today, Greenland has representations in Brussels, Washington DC, Reykjavik and Beijing.

The Greenlandic diplomats are formally part of Danish diplomacy, but in practice report to Naalakkersuisut and the Department of Foreign Affairs in Nuuk. The representation in Copenhagen, which also houses professional staff from departments and government agencies, falls within the Premier’s Office and the head of representation is part of the Diplomatic Corps in Copenhagen.

In parallel, the relationship with the United States has helped drive the expansion of the foreign policy competence of home rule and self-government authorities. In response to a number of cases related to the Thule Air Base, a Foreign and Security Policy Committee was established in 1985 where Inatsisartut (Parliament) members could be informed in confidence, and in 2004 the gained insight and influence on foreign and security policy was formalised in the Itilleq agreement, the provisions of which are found in the Self-Government Act.

Most recently, changes in global climate and shifts in global economic and security balances have turned attention to the Arctic. This has given Greenland more opportunities to establish links outside Denmark. In 2008, Greenland and Denmark, along with the four other Arctic coastal states, signed the socalled Ilulissat Declaration. In the declaration, governments confirmed that they would resolve any disagreement over new borders in the melting Polar Sea amicably and according to UN procedures. At the same time, it reaffirmed the willingness separately and in established cooperation forums, primarily the Arctic Council, to take responsibility for the environment and development, so proposals by, among others, global environmental organisations for an international treaty to protect the momentum lost by the Arctic.

In plans for the financing of future independence, China, following the takeover of the mineral resources area by the Self-Government in 2009, has been high on the list of potential investors. In response to this, in 2020, the United States has opened a consulate in Nuuk that, with the help of American consultants and cooperation programmes, is tasked with increasing the integration of Greenlandic economy and society with North America. At the same time, the US sees the modernisation of bases in Russian Arctic as a threat to the Thule Air Base. It therefore wants increased investment in the defence of Greenland, including with obvious civil/military ‘dual use’. In doing so, more and more of the ‘internal affairs’ of the Self-Government have taken on a security policy dimension and this puts the division of competences in the Unity of the Realm under pressure. If the state insists on deciding as soon as anything is also a security policy issue, it will roll back Self- Government. Conversely, it contradicts the interpretation of the Danish Constitutional Act requiring Danish monopoly to conduct security policy if the Self-Government insists that the state must not interfere.

Further reading

- Education

- Hans Egede and the work for the mission service

- Health and care

- Home Rule (1979‑2008)

- Housing

- Hunting and subsistence economy

- Industry and labour market

- Infrastructure

- Peqqineq – Health and balance

- Plans in Greenland

- Population and demographics

- Premiers of Naalakkersuisut 1979-2022

- Self-Government

- The Continental Shelf Project

- The Greenlandic insular community

- Towns and settlements

Read more about Society and business in Greenland