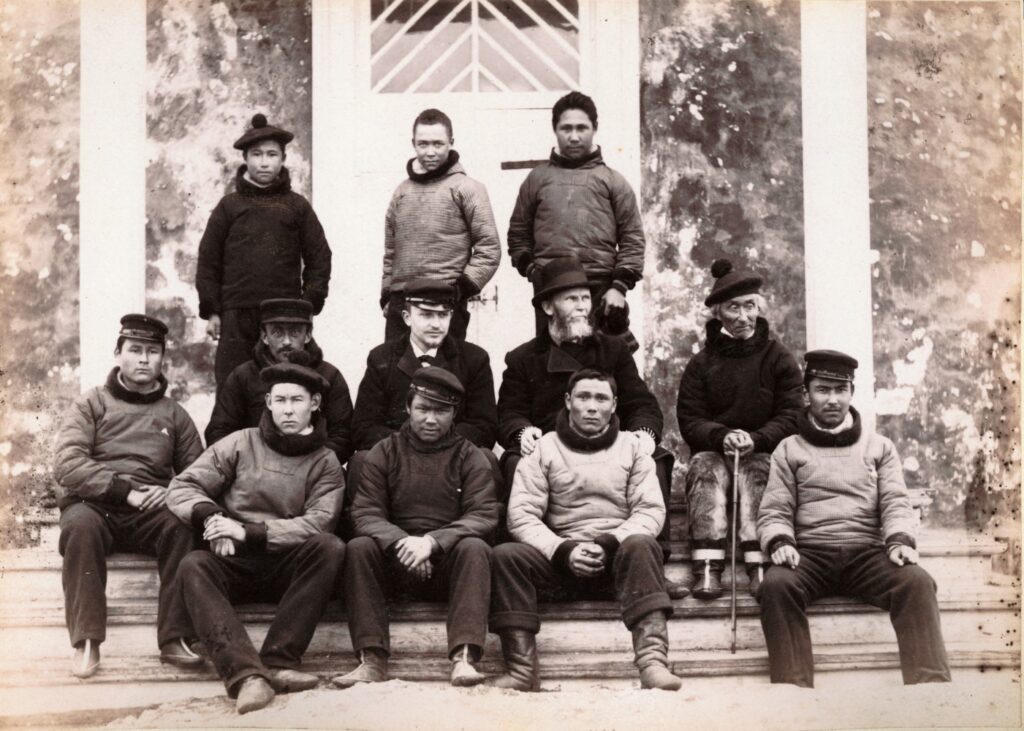

JOHN MØLLER/ARKTISK INSTITUT

Literature has evolved from the anthropological narratives collected by the colonial power over a modernism that discussed, among other things, Greenlandic identity, nationality and traditions in the face of new currents. Increasingly, thematics have become more individualistic, just as Greenlandic writers are increasingly breaking taboos and discussing their own identity.

Time up to 1930

The pre-colonial era was characterised by orally handed down myths and legends intended to enlighten and to preserve tradition and language. With colonisation came the inspiration for collecting these myths and legends, and from 1857, South Greenland’s inspector, H. Rink, published the Kaladlit Oqalluktualliait/Grønlandske Folkesagn (Greenlandic legends), which consisted, among other things, of manuscripts by Aron of Kangeq and Jens Kreutzmann of Kangaamiut.

In 1921‑1925, Knud Rasmussen published Myter og Sagn fra Grønland (Myths and Legends from Greenland), collected during The Literary Expedition in 1902‑04 and the Fourth Thule expedition in 1919.

Wanting to help build the country, H. Rink set up the first book printing house in Godthåb in 1857, publishing the first book, Pok, in 1857, and in 1861, he founded the first Greenlandic newspaper Atuagagdliutit. From 1861, the chief catechist Rasmus Berthelsen was editor of Atuagagdliutit.

The literature that could now be published by the printing house was characterised by religiosity and patriotism.

Modernism

Among the pioneers were Josva Kleist and the poet priest Henrik Lund, who in 1912 wrote the lyrics for Nunarput utoqqarsuanngoravit, adopted as the national anthem of Greenland in 1916, with music by Jonathan Petersen. In 1921, Lund published Erinarssûtit, a folk song book that has contributed to national consciousness.

The Act on the Greenland Provincial Council of 1911 gave the population new requirements for the country’s development. The population and writers participated in the debate on Greenlandic identity. Representatives of the progress were seen in the first two Greenlandic novels: Mathias Storch’s Sinnattugaq in 1914 (En Grønlænders Drøm (the Dream), 1915) and Augo Lynge’s Ukiut 300-nngornerat in 1931 (300 år efter (300 years later), 1989). They criticise their own time, demand change and produce a vision of the future in which Greenland has developed into a society full of wealth and equality.

Romantic nationalism

From 1930‑1950 onwards, the welleducated elite, with outside inspiration, wrote poems, songs, plays and novels. The great changes that occurred made it natural to strengthen national consciousness and seek a cultural and identity standpoint in romanticised depictions of bygone days, the dream of change and confidence in one own’s strengths. Frederik Nielsen wrote Greenland’s first collection of poems Qilak — nuna — imaq (1943) and several novels, including Tuumarsi (1934) and Ilissi tassa nunassarsi. Pavia Petersen wrote the first contemporary comedy, Ikinngutigiit (1934) and posthumously Niuertorutsip pania (1944) about the life of the daughter of a mixed marriage. With Ersinngitsup piumasaa (1938), the allround artist Hans Lynge depicted the pre-colonial era when codes of honour force two brothers into an unhappy killing.

Mental decolonisation and breakup

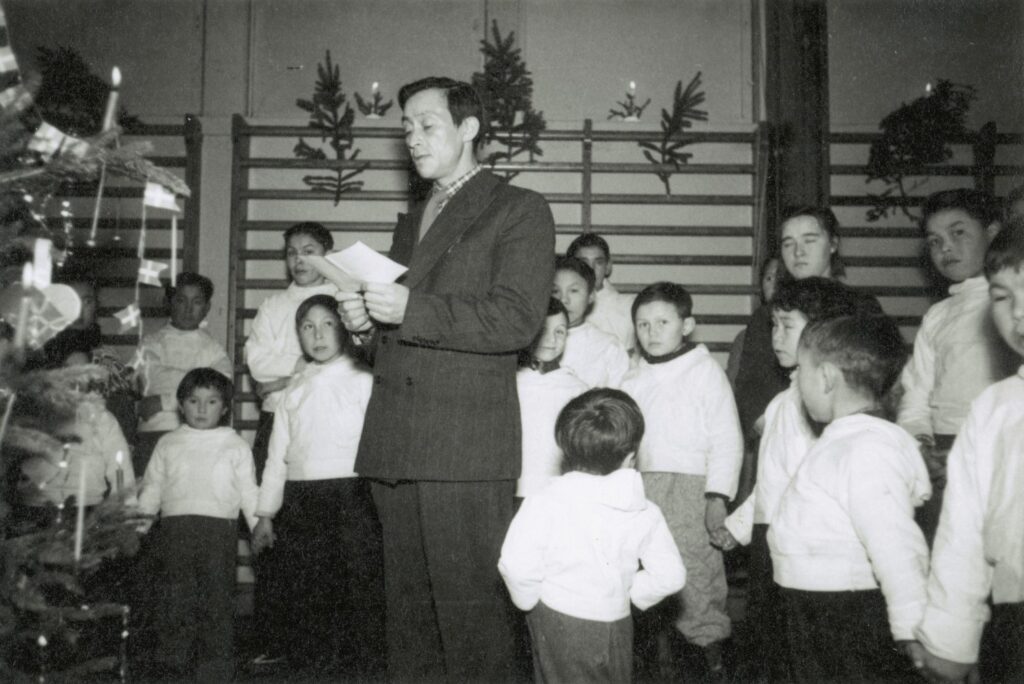

NIELS ERIK THYGESEN/ARKTISK INSTITUT

After the amendment of the Danish Constitutional Act in 1953, Greenland was incorporated into the Danish kingdom. The Greenlanders adopted a wait-and-see and not always enthusiastic attitude, and the following years of literature was marked by protest against the upheaval of society.

Many kept focusing on the past, as seen, for example, in the novel Nunagssarsiak (1954) by Ulloriannguaq Kristiansen, which tells the myth of the struggle of the Greenlanders and Norse. Otto Rosing’s novel Taseralik (1955) pays tribute to the ancestors and describes colonial Greenland and the annual summer camps of the mid-19th century.

The debate over centralisation and depopulation of the settlements is seen in Ole Brandt’s 1971 cult novel Qooqa, which urges compatriots to fight against development and to believe in their own experience. The authorship of the priest Otto Sandgreen was based on source material collected from elderly people in the outermost regions. The main work, the novel Isi isimik kigullu kigummik (1967) (An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, 1987), describes soul loss and blood feud in an East Greenlandic family of shamans. Sandgreen continues this line with his biography Georg Quppersimaan: Taamani Guutimik nalusuugama (1972) (Min eskimoiske fortid (My Eskimo past), 1982), in which he tells, via the memoirs of Georg Quppersimaan, of the life of an East Greenlander before his conversion to Christianity. With the collection of poems Nalusuunerup taarnerani (1965), Villads Villadsen described in lyrical form both East Greenland and the clashes of the past between the Norse and Inuit.

From the late 1960s to the home rule in 1979 – and the time thereafter – a number of angry young men put the resistance into words. The protest poetry that followed in the wake of the student revolt in Europe was led by Greenlandic students in Denmark, such as Aqqaluk Lynge, Moses Olsen and Aqigssiaq Møller. They embarked on a new and central theme, homesickness, and took a critical perspective on Denmark’s presence in Greenland. The style was confrontational with a keynote of anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism. The themes revolved around the unfortunate repercussions of the new arrangement, and concepts such as identity crisis and alienation emerged.

Poetry as a weapon in the political struggle is seen in Moses Olsen’s short story Aamma uagut taamaappugut? from the collection of poets and short stories Allagarsiat (1970), which portrays the consequences of modernisation and a subdued people. Aqqaluk Lynge satirises what the Danes have accomplished in the poem Ode til Danaiderne (Ode to the Danaids) from the collection of poems Tupigusullutik angalapput (The Veins of the Heart to the Pinnacle of the Mind, 1982). He sees the Danes as power seekers who discard the Greenlandic people and practice inhuman humanist imperialism. Lynge clearly addresses the Danes, just like Jens Geisler and Aqigssiaq Møller.

Individualist writers and global influence

In 1979, Greenland gained home rule, and the authors gloomily described the change of times, but now also focused on individual issues. In 2010, Kristian Olsen Aaju wrote Greenland’s first crime novel, Kakiorneqaqatigiit. Hans Anthon Lynge published Umiarsuup tikinngilaattaani (1982), Allaqqitat (1997) (Bekendelser (Confessions), 1998) and co-authored the screenplay Heart of Light (Qaamarngup uummataa) (1997).

One of the first female writers, Mâliâraq Vebæk, focuses on the oppression of women and the problems that can arise from the Greenland–Danish culture clash in his Bussimi naapinneq of 1981 (Historien om Katrine (The story of Katrine), 1982) and Ukiut trettenit qaangiummata from 1992 (Tretten år efter (Thirteen years later), 1997). With Grethe Guldager Thygesen’s Kalaaleq arnaq (1984) and Dorthe Nathanielsen’s novel Aani (1986), the depiction of female life takes a place in literature.

Although views and literary expression could still be trenchant, the period leading up to and following the introduction of self-government in 2009 became more diffuse and characterised by more voices. The diversity of literature now allowed for taboos to be broken, individualism and avant-garde art. Jessie Kleemann caused outrage with her avant-garde and provocative poem collection Taallat in 1997.

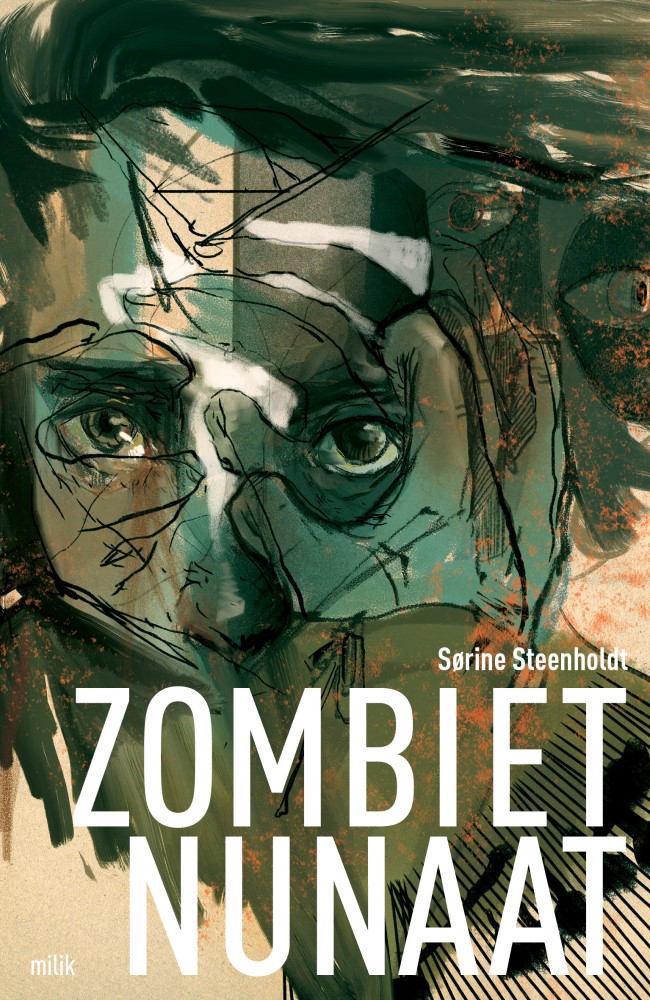

MAJA-LISA KEHLET (ILLU. COVER) OG ULANNAQ INGEMANN (PORTRÆT) /MILIK PUBLISHING, 2015

New currents with individual issues and tackling taboos in society are seen in Vivi Lynge Petrussen’s Naalliutsitaanerup pissaanerani (2001) on domestic violence. Kelly Berthelsen describes sexual abuse, alcoholism and substance abuse with Misigissutsit: Taallat in 2000 and in Tarningup ilua in 2001 (En sjæls inderste kammer (The innermost chamber of a soul), 2002).

Otto Steenholdt embarks on the horror genre of qivittut/mountain wanderers with Inuillisimasup ikioqqunera (Et råb om hjælp (A cry for help), 2001/2014). With the novel Tarrarsuummi Tarraq in 1999 (Saltstøtten (The pillar of salt), 2000) and the short story collection Uumasoqat in 1992 (Det andet dyr (The other animal), 1998), the provocateur Ole Korneliussen brought phenomenology, existentialism and human being into literature. The lyricist Marianne Petersen, nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 1993, adds burlesque and grotesque humour to her poems.

Many writers paint, write and make music, e.g. the visual artist Frederik ‘Kunngi’ Kristensen is also known for his poems.

Individualistic issues and breaking taboos

In 2012 and 2014, NAPA (Nordic Institute in Greenland), Nunatta Atuagaateqarfia (Central Library of Greenland), NUIF (Nuuk Youth in Progress) and Milik Publishing organised the short story competition Allatta! for young people between the ages of 15 and 25. It brought a breakthrough in Greenlandic literature with two short story collections and several spin-offs, including a novel by Niviaq Korneliussen, HOMO sapienne (2014), about finding your gay identity, a short story collection by Sørine Steenholdt, Zombiet nunaat (2015) (Zombieland) describing vulnerable people and abuse, and a short story and poem collection by Pivinnguaq Mørch, Arpaatit Qaqortut (2015), depicting existential themes of life and everyday challenges. As the first author, Niviaq Korneliussen was successful in her complaint against the refusal of support from the Danish State Art Foundation and wrote her second novel, Naasuliardarpi (2020) (Flower Valley), following a grant. The novel, which in 2021 won the Nordic Council Literature Prize, describes grief at witnessing suicide and feeling different.

Many of the young writers are so secure in their identity that they can negotiate it or criticise parents, society and their compatriots. Taboos are broken and the view is individual with local issues, but also international and innovative both in style and content.

Further reading

- Hans Lynge and Jens Rosing

- Home Rule (1979‑2008)

- Language

- Music

- Population and demographics

- Religion and religious communities

- Self-Government

- The colonial period until the war years

- The Inuit culture, precolonial period

- The media in Greenland

- The Norse

- Traditions and tales

- Visual arts and crafts

Read more about Culture in Greenland