ERIK PETERSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 1952

With the onset of World War II, Greenland became part of the United States’ sphere of interest and several military facilities were established in the country. When Denmark was liberated in 1945, the connection could be resumed and in 1948, the Greenland Commission was established. The aim was for the Danish-Greenlandic cooperation to come up with proposals for reforms that would help to develop Greenland.

In 1953, Greenland was formally given equal status with the rest of the Danish kingdom, and the development that took place in the following years was governed from the Ministry for Greenland in Copenhagen. The development took place according to the Danish role model and often described subsequently as ‘danification’. The focus was especially on business development, urban development, as well as education policy.

Greenland during World War II

On 9 April 1940, Denmark was occupied by Germany, and Greenland suddenly stood on its own two feet. Although the Danish government continued after 9 April, in the circumstances, Greenland was unable to receive directives, goods or new personnel from Denmark.

The President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, proclaimed that Greenland was part of the United States’ sphere of interest and that the Danish government was thus, technically, hostile. The two governors in Greenland, South Greenland’s Aksel Svane and North Greenland’s Eske Brun, were the chief representatives in Greenland and could, by way of the applicable local government act for Greenland from 1925 and in exceptional cases, ‘take such measures as the people’s best interests may require.’

The primary objective of the governors during the war was to retain Greenland as part of Denmark and, moreover, continue the determined political line. In addition, the governors had to retain the support of the two Greenlandic Provincial Councils in order to continue the governance of Greenland. The two Provincial Councils had an advisory function on policy in Greenland, but Danish entitlement to Greenland was based on precisely trust and willingness to cooperate between Danish colonial rule and the Greenlandic population.

US military engagement

The Greenland policy aimed at developing society towards the opening of the country. One element of this was that over time Greenlanders had to have more and more influence over their own affairs, so that in the long term, society would be able to cope on its own. On this basis, a joint provincial council meeting was held at the beginning of May in 1940 at which the Greenlandic positions were presented. The meeting ended with two statements; one for King Christian X and one for President Roosevelt.

The message to the King expressed regret at the situation, while a gesture of friendship was given to the United States in the message to Roosevelt. Subsequently, diplomatic and trade relations were established with the United States and Canada to replace the lost connection to Denmark. Initially, it happened by both countries sending consuls to Greenland, and a US Coast Guard ship was deployed to patrol the waters.

The strategic importance of Greenland was highlighted during the course of the war. The 1941 Defence Agreement between the United States government and Denmark’s envoy in the US, Henrik Kauffmann, ushered in the United States military involvement in Greenland, which is still in force. The agreement was reached by bypassing the Danish government, but Denmark’s liberation government adopted the agreement as one of the first decisions shortly after Liberation in May 1945.

Cultural encounter and fraternisation ban

During the war, the United States set up a number of military facilities in various locations in Greenland, of which the South Greenland base in Narsarsuaq was the largest with up to 6,000 American soldiers. The population of Greenland at the time was roughly 20,000, so the relatively large American presence invariably had an impact on societal development. On the part of the colonial administration, the focus was on continuing the protection of Greenlandic society.

Gradually, a fraternisation ban was instituted and controllers were placed at the military installations. They were to ensure that there was no contact between the Greenlandic population and the American troops. On the part of the Greenlanders, however, there was a great desire for contact with the American troops. In many ways, the American presence was an eye-opener, partly through the Greenlandic population gaining insight into a different way of doing things, partly by seeing the USA’s ability to implement initiatives, such as the establishment of the military bases, which led the thoughts of many towards the possibilities of a industrialisation of fisheries in Greenland.

Cryolite exports and increased passenger transport

KAJ SKALL SØRENSEN/ARKTISK INSTITUT, 1953

During the war, the Greenlandic population maintained trust in Denmark, despite the broken connection and the American presence. Greenland’s role in the Allies’ struggle against the Axis powers was quite significant in several respects: Greenland provided the land for US military installations, including the runways that were the prerequisite so that the United States would send bombers to Europe. and through the Northeast Greenland Sled Patrol, later known as Sirius, German attempts to establish themselves in Northeast Greenland were thwarted. Meteorological observations in the waters off Northeast Greenland were also important as the weather in northwestern Europe is affected by the weather systems there.

The cryolite mine by Ivittuut in Southern Greenland was of special significance; it was the only one of its kind in the world, and the cryolite was used for aluminium production and was thus essential to the war industry. The cryolite from the mine was sold to the United States and Canada, and in this way the supply of goods for Greenland was financed.

The supply of goods had so far been shipped directly from Copenhagen to the colonial towns, after which the goods were sailed on to the smaller locations in the district. This meant that there was no significant contact between the colonial districts as there was no organised passenger traffic. During the war, due to the reduced freight capacity, transit ports were established from which smaller ships distributed the goods. It created increased contact between the different parts of the country, including through passenger transport.

The possibility of replacing personnel was poor and, in consideration of the situation, a centralisation of the administration was implemented, in which Nuuk became a kind of capital. The two provincial councils held joint meetings and decisions could be implemented faster than before.

The media during World War II

During the course of the war, several media were created in order for the population to be kept up to date on developments in the world: The Danish-language newspaper Greenlandsposten, which was later merged with the Greenlandic-language Atuagdliutit, today called A/G, opened up the dialogue between Danes in Greenland and those Greenlanders who could speak and understand Danish.

The radio service expanded and sales of radios increased quite significantly. So many people in Greenland got a sense that the world was getting closer and that Greenland was part of the world. Developments during the war gave Greenlandic society a new direction and a greater awareness in the population of what development was going to happen. Upon the liberation of Denmark in May 1945, the Greenlandic society was therefore quite different from the one that felt as if it was thrown into the deep-end in April 1940, when contact with Denmark was broken.

The initial post-war period

In May 1945, the announcement that Denmark was liberated was received with great joy in Greenland. The relations with Denmark could be resumed, and the Greenland National Council now saw the development that had occurred in Greenland during the war. Therefore, the idea was initially that conditions should return to pre-war status before any sweeping reforms were launched.

Around the turn of 1945/1946, the Greenland Provincial Council and representatives from the two Greenland provincial councils entered into the first negotiations on Greenland’s future, but these did not result in major changes. Based on developments during the war, the Greenlandic representatives had a number of requests, but initially had to arm themselves with patience.

The Greenland Commission is established

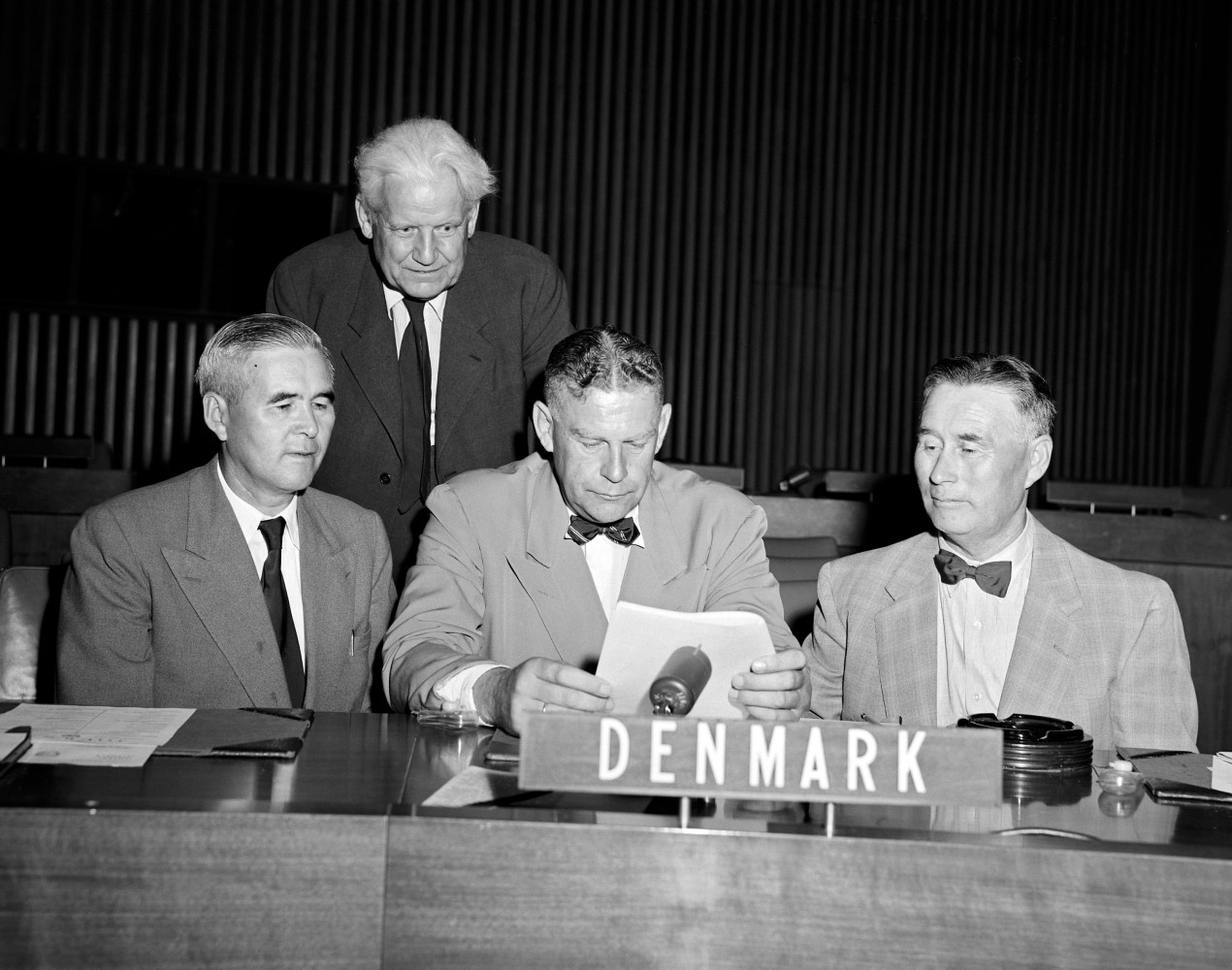

MB/UN PHOTO, 1954

In the summer of 1946, a Danish press delegation travelled to Greenland and reported on awful conditions in the country, including poor health conditions. Denmark was criticised for defaulting on commitments in Greenland, and the Greenland Provincial Council and the Danish government now came under pressure over the Greenland policy. The United Nations (UN) was created in 1945, and one of the organisation’s objectives was for non-autonomous areas to change status from colonies to countries with autonomy or self-government.

From within, from the Greenlandic politicians, there was also pressure for a change in Greenland’s colonial status. The retention of the country as part of the Danish kingdom was thus challenged from several sides. A new Danish government was formed in late 1947 led by Prime Minister Hans Hedtoft. Eske Brun, who had served as a bailiff in Greenland during the war, was employed in a newly created position in the Greenland Provincial Council.

Hedtoft and Brun jointly formulated a master plan for the future of Greenland, which was presented at the joint Provincial Council meeting in the summer of 1948. The plan was intended to strengthen ties and cooperation between Greenland and Denmark and contribute to the modernisation of society. The provincial councils gave their approval of the plan, and in the autumn of 1948 the Greenland Commission was established, broadly composed of Greenlandic and Danish members.

The task of the Commission was to propose reforms for the development of Greenland. As early as 1950, the Commission delivered its report, known as the G-50.

Greenland is formally given equal status with the rest of the Danish kingdom

A number of acts of the Danish Folketing followed on the basis of the Commission’s report, including the centralisation of the provincial councils and of the administration. In terms of the constitution, Greenland was included in the revision of the Danish Constitution, and when the law came into force on 5 June 1953, Greenland was formally seen as an equal part of the Danish kingdom.

The process of the inclusion of Greenland in Denmark showed clear interests from both sides in maintaining the link between the countries. Denmark’s interests had roots in the security-political trends of the time, including the relationship with the United States, while Greenland saw a clear advantage in continuing the long-standing relationship with a valued partner.

In 1951, a new defence agreement between Denmark and the United States regarding Greenland was entered into. Against that background, the United States continued its involvement in Greenland, this time with the emphasis on the Thule Air Base at Pituffik, which was established in 1951. The local Inughuit population of Thule was, for the sake of a planned expansion of the Thule base, forcibly relocated shortly before the Danish Constitutional Act came into force.

In the field of security and foreign policy, there was no involvement of Greenlandic politicians when decisions were to be taken in the early 1950s. At the same time, the pace of development had increased significantly and, as a result of these actions, it soon became apparent that the population was finding it difficult to come to terms with the major changes that were happening.

Modernisation of society

The Greenland Commission’s report in February 1950 provided the framework for the modernisation of Greenlandic society. The following years of development largely occurred with Danish conditions as a direct role model, and the policy used is subsequently often described as ‘danification’. The governance took place from Copenhagen, from 1955 in the Ministry for Greenland.

One of the major tasks was the expansion of the infrastructure which was necessary for the establishment of an efficient business community. The earlier requirement that the administration of Greenland had to balance economically was waived, and in the following years the Danish state built ports, power stations, hospitals, schools, roads, waterworks, etc. From the outset, efforts were made to improve and renew the housing stock. Houses of stone and peat had to be replaced with larger and more hygienic dwellings, often constructed as self-construction projects and with advantageous construction loans.

Private initiatives and business support provide impetus

JETTE BANG PHOTO/ARKTISK INSTITUT, 1961

With the new arrangement, the monopoly disappeared, and thus the way was paved for private initiatives. The first years saw some new kiosks, but gradually shops with a stock appeared that could compete with the Royal Greenland Trading Department. In 1963, the first consumer cooperative was established and today Kalaallit Nunaanni Brugseni has outlets in several towns. Contractors, often stationed Danes, set up private enterprises and increasingly participated in the construction of homes and other buildings and facilities.

The socio-economy was to build on the exploitation of the country’s resources, primarily fishing. Business support made it possible to invest in larger fishing boats and the number of fishermen increased, while the hunting profession gained less importance, except in the outermost regions. The first years focused on cod fishing, but as the cod population decreased, shrimp fishing gained increasing importance, and since then shrimp has been Greenland’s main export product.

While private fishermen expanded the fishing fleet, there was virtually no private investment in factories and other facilities for the processing of the catch. Therefore, this task had to be undertaken by the state, and under the auspices of the Royal Greenland Trading Department (KGH), factories were built to process cod and shrimp.

Investments in open-water towns intensifies

VAGN HANSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 1965

In 1960, the state established the Greenland Committee of 1960, called G-60, which in a report published in 1964 proposed an intensification in investments in both infrastructure and production facilities. Investments were to be made primarily in the socalled open-water towns of Paamiut, Nuuk, Maniitsoq and Sisimiut, where it was possible to fish throughout the year and thus increase production.

Even before World War II, parts of the population had moved from smaller settlements and remote trading posts to primarily the towns. As part of the modernisation, a policy was implemented that would increase the moving from the small settlements. The Provincial Council supported this policy and the municipal councils were required to assess every year which of the inhabited settlements would be developed. These assessments became critical to whether investment should be made in infrastructure at the settlement and whether the population could receive funding for the construction of a new home. In this way, it pushed segments of the population to move to the settlements where the authorities wanted development.

The concentration policy was reinforced after 1960, in continuation of the plans for expansion in the openwater towns. In order to be able to house the many newcomers, concrete apartment buildings began to be constructed, but nevertheless during this period there was a constant shortage of housing in the towns.

Education policy after 1950

REGITZE MARGRETHE SØBY/ARKTISK INSTITUT, 1965

The education policy was also in focus. It had long been felt that good Danish skills and knowledge of Danish culture were a prerequisite for improving the level of education and thus to take over the positions that the Danes had held so far.

The new school law of 1950 opened the possibility that after the 2nd grade – initially in the bigger towns – pupils could follow a programme where Danish was the language of instruction, although except for the subjects Greenlandic and religion. It would, among other things, qualify for admission to secondary school at the same level as a Danish lower secondary school leaving examination.

Between 1961 and 1976, more than 1,500 pupils were sent to Denmark after 6th grade, where they lived with Danish foster families and went to classes in Danish schools. During the same period, four boarding schools were established in Denmark, exclusively for Greenlandic pupils who would continue their schooling after the 7th grade.

Apart from the teachers’ training college in Nuuk, no institutions of higher education were established until 1977, when the Iron and Metal School in Nuuk and the Building and Construction School in Sisimiut were established. Higher education had to be taken in Denmark, and in some places purely Greenlandic classes were set up, e.g. at the business school in Ikast and the pedagogue training college in Aarhus.

In Denmark, several associations for Greenlanders were formed in Denmark and, in several towns, institutions were established to pursue, among other things, the interests of people seeking an education. These still exist in Copenhagen, Aarhus, Odense and Aalborg as the Greenlandic Houses.

Population trends from 1950 to 1975

The many reforms meant major changes in demographic conditions. Along with improved housing standards, targeted action in the health care area meant tuberculosis gradually disappeared in the country. This caused a sharp decline in mortality and thus a sharp increase in the population, almost doubling from 1950 to 1970 from around 23,000 to just under 44,000 inhabitants.

Infant mortality declined dramatically, and child and adolescent groups made up an increasingly large proportion of the population. The average life expectancy increased from about 40 years in 1950 to more than 60 years in 1975. Previously, stationed Danes accounted for a few hundred, but with the new activities, thousands of Danes now came to the country. The so-called summer men were chiefly employed in construction and stayed in the country only during the busy summer period. Some had employment for several years before leaving the country, while others settled down because they had established a family or because they had decided to stay for other reasons.

In 1975, more than 9,000 Danes were living in Greenland, and they made up about 20 % of the population. At the same time, the number of Greenlanders living in Denmark also increased. Most were undergoing education and, for most part, returned to Greenland. Others got married to Danes and chose to stay in Denmark.

Negative consequences of development

The many reforms and investments in the 1950s and 1960s produced distinct improvements in material conditions. At the same time, a number of problems arose that can be interpreted as a result of segments of the population not becoming part of societal changes and ending up as passive bystanders to the developments from which they did not benefit.

A relatively large proportion of the population had no vocational training and thus ended up in a poor employment situation with low pay and risk of unemployment. A large part of this group were people with a traditional Greenlandic upbringing, especially people from the settlements or people who had moved from a settlement to a town. The symptoms were increased consumption of alcohol that could now be freely bought, increased crime and a rising number of suicides.

In political circles and organisations, there was an increasing dissatisfaction that the Greenlandic population did not adequately influence development and ended up as secondclass citizens of society. The situation generated a renewed debate on the framework for development and demands for genuine equality.

The modernisation of society also meant the drawing up of legislation to ensure the legal rights of citizens, but in some cases the opposite occurred: The attempt to send 22 Greenlandic children on a year’s stay in Denmark and then to orphanages in Nuuk in the early 1950s to make them ‘exemplary citizens’, the case of the legally fatherless children and more or less formal adoptions of Greenlandic children happened on the basis of a desire to assimilate Greenlanders, Greenlandic society and Greenlandic culture, but this had major negative consequences for those who were affected.

The impossible equality

AAGE SØRENSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 1953

A clear objective of the modernisation of Greenland was to improve the material conditions in the country, but at the same time on the part of the Greenlanders, there was an expressed desire to create equality between Danes and Greenlanders and that the Greenlandic population should have a real influence on their own circumstances. That, however, did not happen. The development was guided by the Danish authorities and overall decisions were taken in the Folketing and the Ministry for Greenland in ongoing negotiations with the Provincial Council.

The unsatisfactory situation was discussed in the Provincial Council in 1959 which, in a statement to the Folketing, called for real equality, and in the following years the problem surrounding equality was in focus. From the establishment of the first provincial councils, the state’s chief representative in the country had been the chief executive of the provincial councils. The chief executive had approved the members’ proposal for the agenda and been the leader of the meetings. This was now changed to allow the 1967 Provincial Council to elect the chairman from among the members of the council.

ANDREAS LUND DROSVAD/ARKTISK INSTITUT, 1948

The educated Greenlanders did not receive the same wages as their Danish colleagues, and the growing group of Greenlandic civil servants, e.g. teachers, telegraphists and priests, worked side by side with Danish colleagues under the same working conditions, but for smaller wages. They were now demanding the same wages as their Danish colleagues. Instead, the state introduced the so-called birthplace criterion which meant that everyone born in Greenland was remunerated on one scale, while workers who had been born in Denmark and were employed from Denmark received higher wages. The rationale was that wage conditions should be aligned according to productivity and in solidarity with other occupational groups. When Danish employees received more in wages, the argument was that it was necessary in order to attract labour to the country.

The birthplace criterion spawned fierce criticism among educated Greenlanders especially and, for several years, the Provincial Council demanded to have the scheme removed. However, the criticism was not supported by, for example, the Greenland Workers’ Confederation (GAS), as equal pay between Danish and Greenlandic civil servants would create a large wage gap between the different occupational groups in Greenland.

In 1970, the Provincial Council had to recognise that the birthplace criterion affected only a smaller proportion of the Greenlandic population and that it was not possible to find another form that would be fairer. The acceptance of the birthplace criterion was at the same time an admission that equality was not possible in this area.

Women’s equality

The introduction of women’s suffrage in Greenland in 1948 meant that Greenlandic women had a more equal status than in the past, and more were given important societal functions and entered the labour market. Following this, more women expressed their desire for greater influence in society.

In line with the development process, discussions in the women’s associations changed from topics such as family and children to also being about housing policy, education and health matters. Kalaallit Nunaanni Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat aimed to bring together the country’s women’s associations and contributed to a significant expansion of the importance of associations in the field of societal policy. Despite this, there were still comparatively few women in politics and business, but more women now took an education.

With the establishment of political parties in the 1970s, the function of women’s associations as a platform for female candidates in politics disappeared more and more.

The desire for a Greenland according to Greenlandic conditions

Gradually, resistance also spread to other parts of the modernisation. In the mid-1960s, proposals for a new Greenlandic school law were discussed, one of the most important elements being the strengthening of teaching the Danish language. The proposal included a provision that parents could postpone teaching in Greenlandic until the 3rd grade. This met sharp criticism and a fear that such an arrangement would weaken the Greenlandic language.

In 1970, a conference was held in Sisimiut with the participation of Greenlandic politicians and representatives of a wide range of interest organisations with the aim of discussing the future of Greenland. Key topics were discussed, such as occupations, population concentration, school and education, language, social problems, etc., and set out guidelines which, when seen under one umbrella, required a more independent Greenland and policies that targeted Greenlandic conditions to a greater degree. In a special statement, representatives of Greenlandic youth stressed that Greenlanders should be considered a national minority and that they wanted a more politically independent Greenland.

Political trends

With the amendment of the Danish Constitutional Act in 1953, Greenland became, in principle, constitutionally equal to Denmark. In 1959, the Provincial Council invited the Danish authorities to set up a committee to adjust the development of society. The Provincial Council’s invitation expressed a desire to establish a longterm objective. It was granted by the Danish government and led to the establishment of the Greenland Committee of 1960, with Greenlandic and Danish politicians and business representatives as members.

The Greenland Committee and the resulting debate

POLFOTO/RITZAU SCANPIX, 1953

The Greenland Committee and its report became known by the designation G-60. The task of the G-60 Commission was to review the political, economic and administrative conditions. The G-60’s plan was: ‘… to raise the political, social and cultural status of the Greenlandic population and boost their standard of living.’

In Greenland, a resistance to the consequences of the G-60 gradually emerged. The resistance was inspired by thoughts of national identity and international trends about ‘free peoples’. It would promote a more positive view of being Greenlanders, highlighting that Greenlanders were a characteristic people with their own culture, traditions and languages, and that this recognition was important in order for Greenlanders to meet Danes as equals.

There was now a pronounced desire to draw up their own political and administrative systems in accordance with the needs of the country and with greater participation of the Greenlanders themselves. The increased political awareness, including under the influence of simultaneous political developments in Denmark, the Greenlandic students’ association and the Peqatigît Kalâtdlit association, influenced the societal debate. The principles behind the policy in Greenland were now turned towards, and thus also against ‘danification’.

The concept of equality was redefined: In the same way that the Danes had to be understood based on their own prerequisites, the Greenlanders now had to be understood based on their prerequisites, and the natural consequence of this was demands for a development based on ‘a more Greenlandic Greenland’.

Implementing this would require not only fundamental changes in the policy in Greenland so far, but also in the relationship between Greenland and Denmark. The 1972 decommissioning of the coal mining town of Qullissat became the symbol of a failed modernisation of Greenland, where economic considerations were above the considerations of the population and where individuals felt that they had effectively no influence on their own affairs.

Enrolment in the European Community and the Home Rule Bill

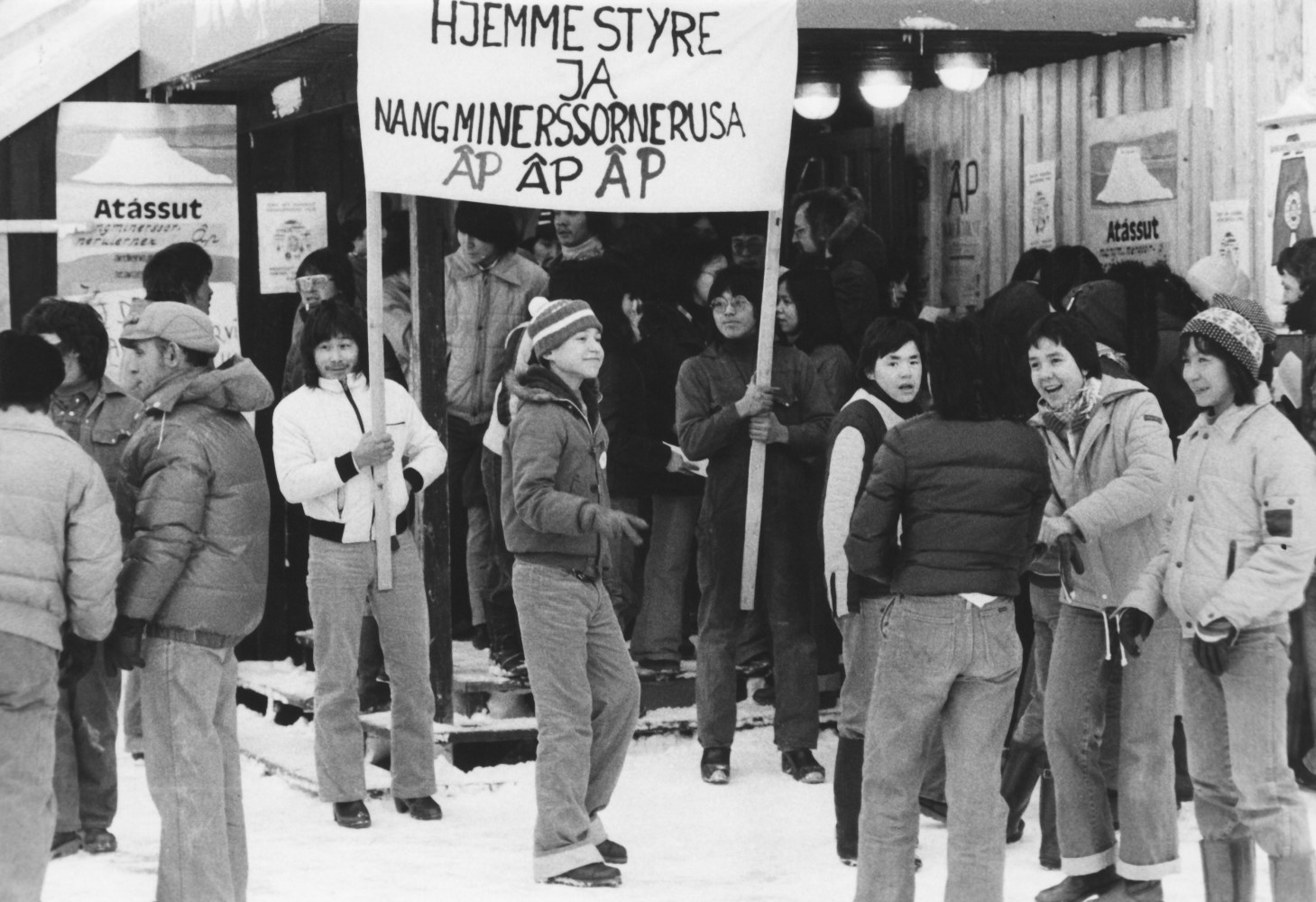

EBBE ANDERSEN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 1979

Since Greenland was formally an integral part of Denmark, Denmark’s desire to join the European Community also meant that Greenland was included in the application. However, while the negotiations with the EC were taking place, there was a change in Greenlandic views on relations with Denmark. A Greenlandic desire for a separate vote for Greenland was rejected by the government. The result in Greenland was a clear no vote to the EC, but when the Danish voters voted yes, Greenland had to follow Denmark into the European Community.

The oil crisis of the 1970s also spawned discussions about the right to the substratum in Greenland. These were also instrumental in political mobilisation in Greenland – a number of parties and associations saw the light of day. Greenlandic youth was a major factor in political mobilisation. For example, the rock band Sume put into words the critical attitude of many Greenlanders towards Danish politics and the desire for self-determination.

The new societal movements had a major impact on developments that occurred in the following decades. A new generation of Greenlandic politicians were elected into the political bodies in the early 1970s and, through their elected positions, proposals for a home rule in Greenland were formulated. The Greenlandic requirements were increased autonomy and participation in their own circumstances, control over the substratum, and that future development would take place, to a higher degree, on Greenlandic terms.

There were substantially different attitudes towards the ties to Denmark. From a desire for rapid independence, to the home rule arrangement being a necessary evil on the road to independence, and finally to Greenland remaining part of Denmark.

Further reading

- Education

- Health and care

- Home Rule (1979‑2008)

- Language

- Literature

- Music

- Population and demographics

- Self-Government

- The colonial period until the war years

- The Unity of the Realm and the Danish State

Read more about History in Greenland