JOHN LEE/NATIONALMUSEET I KØBENHAVN, U.Å.

The Inuit culture is a unified term that embraces several groups of people who still inhabit the Arctic region. The area covers Nunatsiavut, Nunavik, Nunavut, Inuvialuit in Canada, Inupiaq in Alaska and Yupit in Alaska and Siberia, and Kalaallit in Greenland.

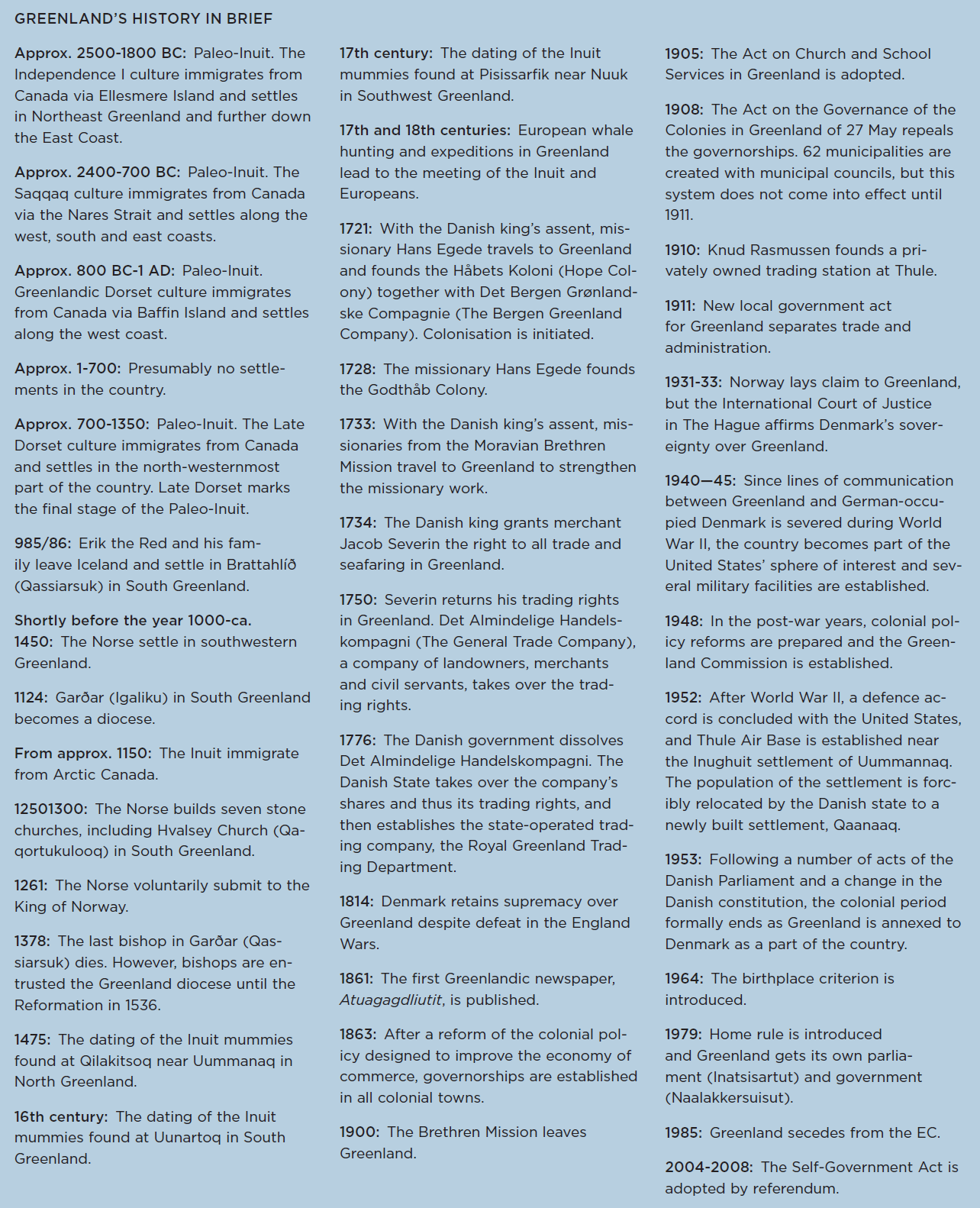

The Inuit immigrated and settled in Northwest Greenland in approx. 1150. A precise dating has not yet been possible, but preliminary dating and typological developments indicate an Inuit presence as early as about 1150.

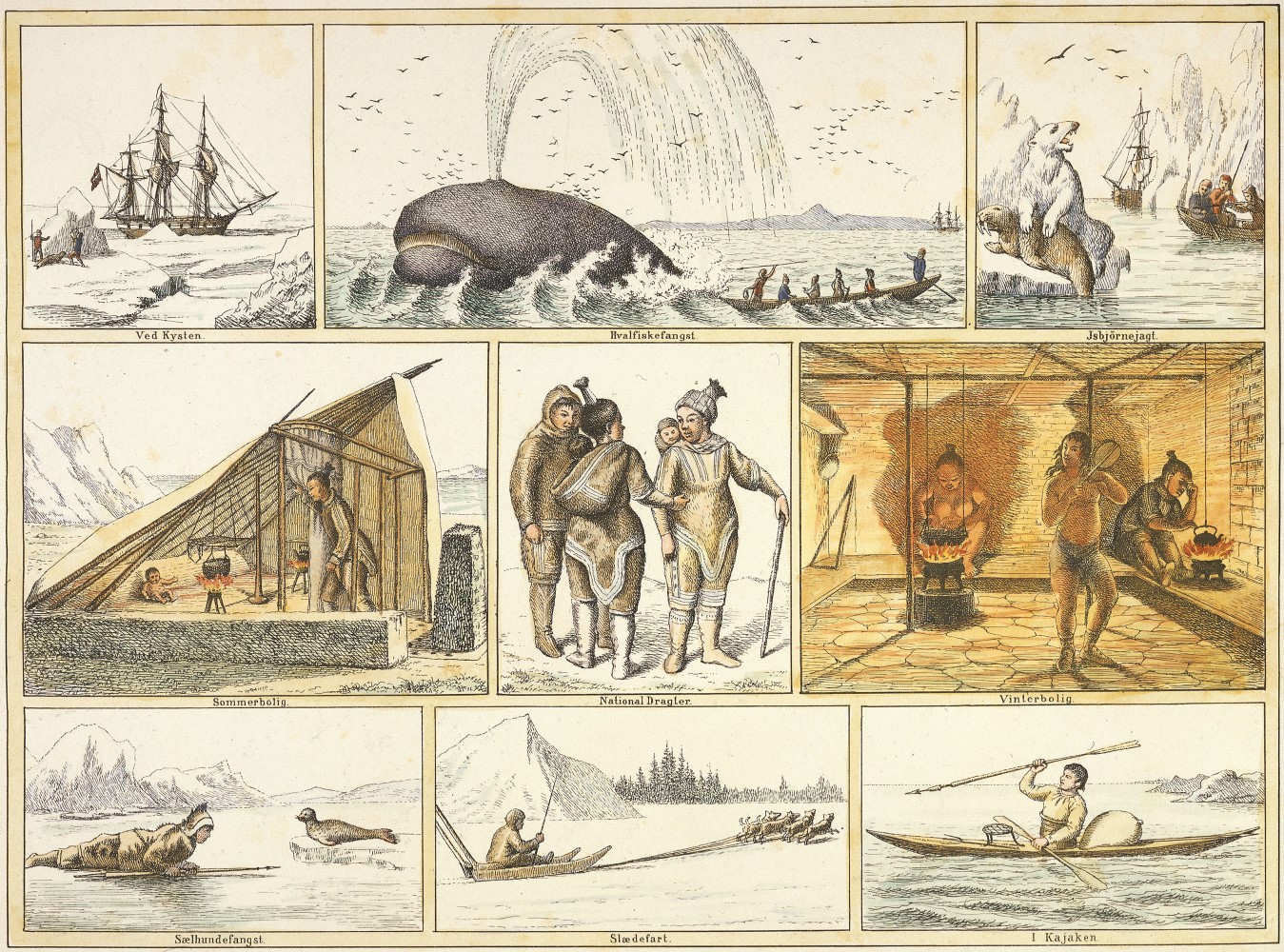

The first Inuit had travelled over 4,000 miles in the space of a few generations from the island of St. Lawrence between Siberia and Alaska to Greenland. The Inuit culture made use of large open skin boats for walrus hunting and whale hunting, as well as kayaking for seal hunting. In winter, dog sleds were used, which allowed the Inuit to hunt over long stretches and quickly occupy new areas.

The earliest archaeological finds in Northwest Greenland have distinct stylistic features in common with the Punuk culture, which specialised in whale hunting in the Bering Sea. In particular, ceramic lamps, excavated in Northwest Greenland, made of clay from Alaska, testify to the rapid movement across Arctic Canada.

Inuit immigration and settlement

EFTER GULLØV, H.C. (1997). FROM MIDDLE AGES TO COLONIAL TIMES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND ETHNOHISTORICAL STUDIES OF THE THULE CULTURE IN SOUTH WEST GREENLAND 1300‑1800 AD. KOMMISSIONEN FOR VIDENSKABELIGE UNDERSØGELSER I GRØNLAND

When the Inuit arrived in Northwest Greenland, the fjords were already inhabited by people from the Late Dorset culture. The cultural encounter between these two groups can be traced archaeologically and in the oral tradition. Tuniit or tunersuit is described in several of the myths as inland fighters, incredibly strong and shy people. They spoke kutattut, which to Inuit sounded like a kind of child’s language.

The abandoned settlement of Nuulliit in the Qaanaaq area offers remains from several archaeological periods, among them winter dwellings constructed by the Inuit in the 1300s. The winter dwellings were partly dug into the surrounding terrain, and the walls constructed in stone, peat and sometimes whale bones. Plank beds were erected along the walls, and the dwelling was presumably lit by small ceramic lamps brought from Alaska, and later by small soapstone lamps. The up to 3 m long entrance tunnel was partially dug down and thus functioned as a cold trap. What sets these winter dwellings apart from later winter dwellings is a special kitchen extension in the front wall next to the entrance tunnel and with access from the space in the dwelling. Analyses of soil layers show that blubber and fatty bones have served as fuel for the kitchen fire.

Yet another element that characterises the early period of Inuit in Greenland are the large ‘qassi’. These structures are erected in the same materials as the winter dwelling, but yet on a larger scale, have narrower plank beds and no traces of cooking. A ‘qassi’ served as a workshop, meeting place where communal hunting was planned, and possibly also as a party house. Traces of tool-making and the large quantities of whale baleen emphasise the orientation of the Inuit towards marine resources, the exploitation of which was a collective task. The organisation of the Inuit whalers was necessary to ensure good and safe whale hunting. A whale hunting team was led by an umialik, i.e., someone who owns an umiaq (a large open skin boat). It took a resourceful family and a good reputation to be able to acquire the title of umialik and to attracting a handful of hunters who would work together as a team and set off in an umiaq in search of the bowhead whale. If the hunting season was successful, the caught whale would ensure food for more families through the winter, while the umialik would rise in reputation and influence.

The harpooner wore a waterproof one-piece suit with a rope of whale baleen attached to it. Having sailed completely quietly up to a sleeping bowhead whale, the harpooner’s job was to jump onto the whale and impale it by the blowhole. When the whale then tried to escape, the harpooner would fall into the water and the team, using the rope, could pull him up, and then they could continue hunting the whale.

Pre-colonial Inuit culture

The period of Inuit culture that runs from the immigration in around year 1150 to the colonisation in 1721 was named the Thule culture by Danish archaeologist Therkel Mathiassen. Since the 1920s, the term has been used to denote Inuit material culture until either the year 1600, where frequent contact with European whalers has been documented, or until 1721, where Denmark formally colonised Greenland. Mathiassen, who documented the culture through finds and excavations, named it after Knud Rasmussen’s 5th Thule expedition, in which he himself took part, and the term is still partly used.

Since an archaeological designation of a still living culture emphasises the ethnocentric view that has often been on Greenland, the term is not used here. Instead, the term Inuit culture is used both for the prehistoric and the contemporary culture, and for the period approx. 1150 to 1721 specifically, the term »pre-colonial Inuit culture« is used.

The woman – duality and balance

KONRAD NUKA GODTFREDSEN, 2012

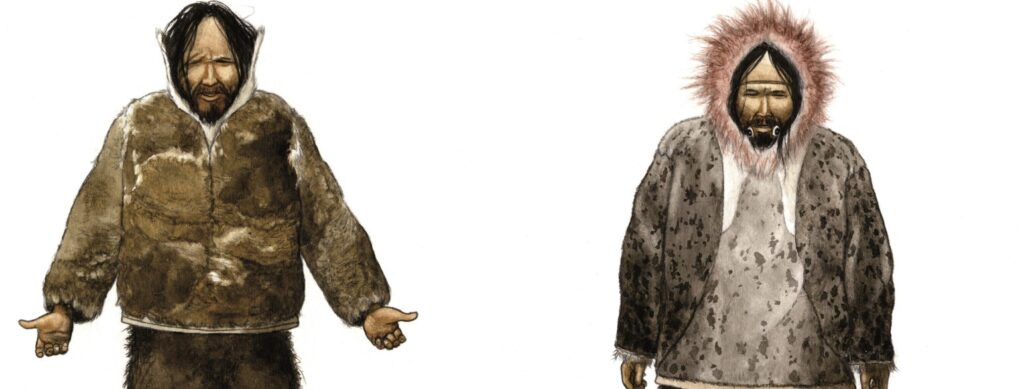

Because of the female cycle, and because she can give birth, the woman was seen as the bearer of a special duality. Like her husband, she had to observe a number of taboo rules, including when she was preparing the game. Both before, during and after the death of an animal, it was necessary to show it respect by observing taboos and thus to thank it for allowing itself to be killed. If the rules were not observed, it would lead to a failed catch.

The taboo rules that the woman had to observe varied from place to place, but might include not using the same ulu (a special female knife) for fish and caribou, for example, or keeping different types of meat separate during cooking.

By observing these rules, the woman helped to ensure the survival of the community, just as everything from the tattoos on her skin, the patterns of her clothing and the way she handled her needlework helped to create a balance between this world, Sila, and the invisible world, Silap aappaa. The taboo rules were thus incorporated into the woman’s daily routine.

Pre-colonial Inuit hunting culture along the west and east coast

Over the course of quite a few generations, the Inuit had migrated both north and south, along the west and east coasts of Greenland. The Inuit followed the seasons and the availability of animals. In the spring, they moved from their winter settlement and began their nomadic season to gather supplies for the next winter. They travelled in large open skin boats and kayaks, wandered inland and slept either in hunter’s beds, a recess quickly built with stones, in rock caves, under open skies or when they stayed in an area for extended periods of time, in tents made of skins.

The harp seal was an especially important resource during the spring months. The seals, which migrated from Canada and southwards, were caught at the mouth of the fjords. At the same time, fishing started for the small capelin, ammassak, which played an especially important role in the planning of the winter supplies. The shoals of ammassat were shovelled up along the shore and laid to dry on the bare rocks or heather to add some natural aroma. After the drying was complete, the ammassat were laid side by side and rolled into a large bundle, which was kept dry and cool until winter.

On land, caribou and hares were hunted with bow and arrow and trout was caught in the rivers. The caribou hunt was an organised, collective enterprise. Shooting hides were set up along the caribou’s migratory routes, and cairns and humans were used to scare the caribou in the right direction, where the hunters were standing by with bow and arrow. After the killing of a caribou, the belly was quickly opened, and the women and men then roughly dismembered the prey before the heavy trek back to the tent camp.

On water, seals were hunted from a kayak by using harpoons and hunting float which would ensure that the seal did not sink before the sealer could reach it. At Sermermiut in Qeqertarsuup Tunua (Disko Bay), fishing lines and nets made of whale baleen have been excavated, so cod, Atlantic wolffish and Greenland halibut have probably also been part of the menu.

Multi-family homes

In the mid-1600s, the rectangular communal house made its appearance. Before, when up to three families lived together under one roof, now four to six families could do the same, or about 20‑30 individuals. They shared the catch, supplies and fuels for both light and cooking. The communal house was conceived and erected by the Inuit whale hunting teams and their families who constructed them along the coastal stretches, and only rarely inside the fjord systems.

The archaeologically recorded communal houses usually measure 4‑5 m in width and 8‑10 m in length, while some have measured to be over 20 m. The house had up to three windows that consisted of gut skins, which had been gutted, dried and stretched before being stitched together and firmly fixed on a wooden frame. The peat- and stone-built walls were covered internally with skins that kept the draught out and at the same time kept the dried ground in place. The plank bed ran the entire length of the main room, which was divided into family units separated by curtains made of skin.

In the limited space in front of each unit, there was a wooden lamp stand for the soapstone lamp, over which a soapstone pot could be hung, while wet skin clothing hung from a drying rack under the ceiling. On the edge of the plank beds, the women sat and sewed skin garments with great care.

New and old tales

LEIFF JOSEFSEN/SERMITSIAQ, 2012

The Inuit did not use written language, which is why oral tradition played a crucial role. A distinction was made between newer and old tales. The newer ones dealt with events the storyteller had heard of first-hand, or from a second or third source, and the old ones were passed down from the ancestors over several generations.

The old tales were to be passed down as originally told as possible. They had entertaining elements, but at the same time they had to convey the norms and values of society to the next generations. Another important element of the old tales was that by telling from an ‘us’ point of view, they created a sense of community.

In these tales it is not only the Inuit who are depicted as being compared with Tuniit, Europeans or other cultures. Tales are also told about mythical and supernatural beings, e.g., Sassuma Arnaa (Mother of the Sea), and how the Sun (Maliina) and Moon (Aningaaq) came into being.

The tales put into words how the world had come into being and what taboo rules the Inuit had to adhere to in order to maintain balance, e.g. by warning of the dangers of incest. They also passed down more simple rules to live by for children and adolescents. For example, by telling that it could be dangerous to move too far away from the settlement when a socalled mountain wanderer, a ‘qivittoq’, could capture you, or by allowing them to understand which plants you should not eat.

Cultural encounters

MANSELL COLLECTION/SHUTTERSTOCK/RITZAU SCANPIX

From the arrival of the Inuit in Northwest Greenland, they met with both the Tuniit and the Norse. Meteoric iron was found in the area, which was an important trading commodity. Through cold forging, the Inuit processed the iron by hammering it into the desired shape. The Norse had several iron objects which they could exchange for other items, e.g. a ring from chainmail has been excavated from Nuulliit and several artefacts have been excavated at Sermermiut.

These early cultural encounters are supported by the oral tradition, which reports of friendly encounters between the Inuit and the Norse, but also of disputes and even a tale of the last of the Norse of Nuuk Fjord who saw his kinsmen depart from Greenland.

AKG-IMAGES/RITZAU SCANPIX

From the mid-16th century to the 18th century, European expedition ships and whale hunting ships travelled along the west coast of Greenland. Trade opportunities quickly arose between the Europeans and the Inuit. Knives and needles of iron, but also glass beads, sugar and tobacco were traded in exchange for skins and walrus and narwhal tusks. The Dutch sailmaker knives were especially popular as they were made of metal and had the same shape as the Inuit women’s main tool, the ulu, a knife used both to cut up and scrape skins.

Before long, the European presence became a driving force for long-haul travel, especially for the Inuit who travelled from the country’s southern and eastern regions. According to the oral tales from East Greenland, the organised trading journeys could last for several years.

The skewed distribution of European commodities, as well as natural resources that characterise different regions in Greenland, was then traded internally among the Inuit. Qeqertarsuup Tunua (Disko Bay) had large supplies of baleen and whale oil, while there was a lack of wood, caribou skins and soapstone. Therefore, in order to obtain the best quality of soapstone for the production of lamps and pots, you had to trade with Inuit from the Nuuk area, while the area by Sisimiut was rich in walrus and caribou. In South Greenland, where the Inuit made more use of fishing, there was insufficient baleen to make fishing lines, while they themselves were rich in foxes and driftwood.

In 1636, Copenhagen shipowners were granted royal privilege to carry out whale hunting in Greenland, and they were officially encouraged to abduct Inuits aged between 16 and 20, who were to be taught ‘about the fear of God, the language and the art of academics’. The last abduction took place in Nuuk Fjord in 1654, presumably from the settlement of Ersaa at Sermitsiaq, a little north of Nuuk. David Danell abducted six Inuit, of which a boy jumped overboard, an elderly woman was put ashore, while Ihiob, Cabelou, Gunnelle and Sigjo were taken first to Bergen and then to Copenhagen.

An unknown number of Inuit were additionally abducted by British expedition ships, some of whom managed to escape after arriving in the British Isles. In 1682, a man in a kayak was seen rowing past Eday, and in 1684 another man in a kayak by Westray, both of these locations belonged to the Orkney Islands. In the early 1700s, an Inuit man drifted ashore at Belhelvie in Scotland in his kayak, but died shortly after arriving. These three episodes quickly turned into legends in Scotland, and the men were called Finnmen. Two of the kayaks are currently on display in Edinburgh and Aberdeen.

In the early 1700s, Inuit had considerable experience with the visiting whale hunting and expedition ships; from 1719 until 1721, between 50 and 100 whale hunting ships arrived in the country every year. In 1721 alone, 104 ships from the Netherlands and 14 ships from Hamburg were whale hunting by West Greenland.

Further reading

- Hans Egede and the work for the mission service

- Inuit hunting culture

- Inuit way of life

- Paleo-Inuit

- The colonial period until the war years

- The Norse

- The strong Tuniit people

- Traditions and tales

Read more about History in Greenland