ANINGAAQ R. CARLSEN/VISIT GREENLAND, 2021

Uummannaq means ‘invigorating’ or ‘heart-shaped’ and is named after the town landmark, the 1,170 m high mountain north of the town. Unlike most other colonies, Uummannaq was not given a Danish name, but was formerly spelled Umanak. The town with 1,428 residents (2021) is located on a roughly 12-km² large island in a sprawling and beautiful fjord system with high steep mountains and at the head of the fjords you will find active and productive glaciers. The inner part of the fjord system has a mainland climate and thus often high pressure and limited precipitation. In winter, there is meter-thick ice in large parts of the fjord, so that you can drive by car to many of the settlements. Uummannaq is known for its many hours of sunshine (2,000 h/year).

History of Uummannaq

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Europeans, primarily the Dutch, hunted for whales in the fjord system and engaged in tusk trade and other interaction with the Inuit population. This was considered problematic by the Royal Greenland Trading Department (KGH), but it was not until 1761 that a more permanent station was established for the Danes, and so the colony of Umanak was founded in 1763. Sealskin, narwhal and walrus tusk as well as polar bear skins were the main sources of income in the colony until the post-World War II modernisation.

From 1933 to World War II, marble was quarried in Mârmorilik (later Maarmorilik) relatively close to the settlement of Ukkusissat. Up to 300 workers, mainly from Denmark, lived in a barrack town by the open marble quarry. Besides modest interaction with the local Inuit, the marble quarry had limited impact on the district.

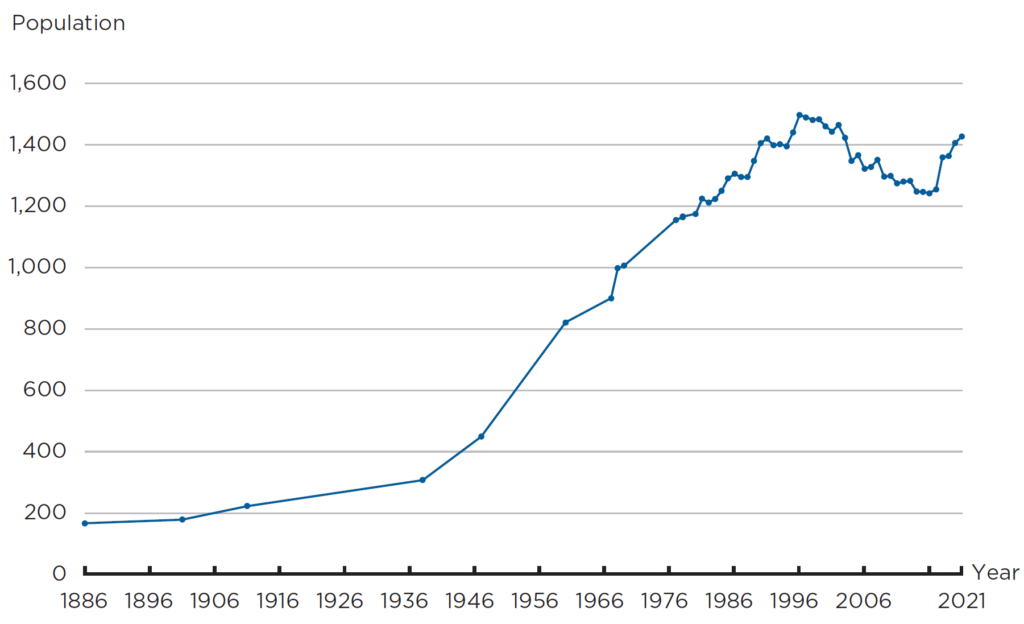

Until the modernisation after World War II, the colony of Umanak, with its many remote trading posts and settlements, served as mainly a hunting district and was relatively isolated. Still, the population gradually moved from the smaller settlements to the colony, which in 1938 had a population of 308, which grew to 449 by 1948, while 1,041 people lived in the district’s remote trading posts and settlements.

STUART MCINTYRE/BAM/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2015

During the post-war years, the district’s revenue from seal hunting was in sharp decline, and the increasing fishing for Greenland shark was unable to compensate for the loss of revenue. The Danish administration’s central reports, the Greenland Commission of 1948 (G-50) and the Greenland Committee of 1960 (G-60), which formed the basis of the modernisation, both assessed that the district did not have an adequate business base and recommended partial depopulation. Relatively many people were convinced to move to Qeqertarsuup Tunua (Disko Bay) or further south to join the cod fishing and fishing industry – however, only few were successful. Some went back, several of them to live as hunters across the district’s settlements and smaller residences. Referring to G-50 and G-60, only modest investments in infrastructure were made in the district and the population was among the poorest in the country.

Marble quarrying at Maarmorilik was resumed from 1966 to 1973. From 1973, a lead and zinc mine, named the Black Angel after a distinctive marking on the mountainside, was started in the old marble quarry. The mine tunnel was located at approx. 600 m’s height, and the ore was transported by cableway down to the crushing mill at the old marble quarry. The mine employed 200‑360 people. Around 20 % of the workers where Greenlandic, many of whom came from the district. Subject to current rules and collective agreements, local Greenlandic workers received a lower salary than non-local workers, which, in 1977 led to the first real strike for equal pay in Greenland and where the National Confederation of Trade Unions of Greenland was one of the negotiating parties.

The Black Angel was decommissioned in 1990. There were plans to reopen the mine in 2010 and some preparations were made until 2015, but mining operations never resumed.

At the end of the 1970s, fishing and trading of Greenland halibut experienced a boom, which meant that the district’s residents gradually went from being among the poorest to being among those with the highest average household income, especially in some of the settlements. Fishing of Greenland halibut makes Uummannaq one of the districts that, measured per capita, contribute the most to export income. Greenland halibut is caught from dinghies in summer and using dog sled or snowmobile and longline during ice formation, which is why the distance from fishing ground to fish factory must be as short as possible. People has therefore largely remained in the district’s seven settlements, and in 2017, 981 out of the district’s 2,236 residents lived in the settlements.

In 2017, the district’s two northernmost settlements, Nuugaatsiaq and Illorsuit, were hit by a tsunami as a result of a major mountain landslide, and the two settlements were evacuated. The about 170 evacuated citizens were mainly relocated to Uummannaq or the other settlements in the district. In the summer of 2021, geological surveys identified a risk of more and larger mountain landslides in the fjord system, which led to considerations to evacuate several of the settlements in the district.

Development and geography of Uummannaq

KÅRE HENDRIKSEN, 2020

GRØNLANDS STATISTIK

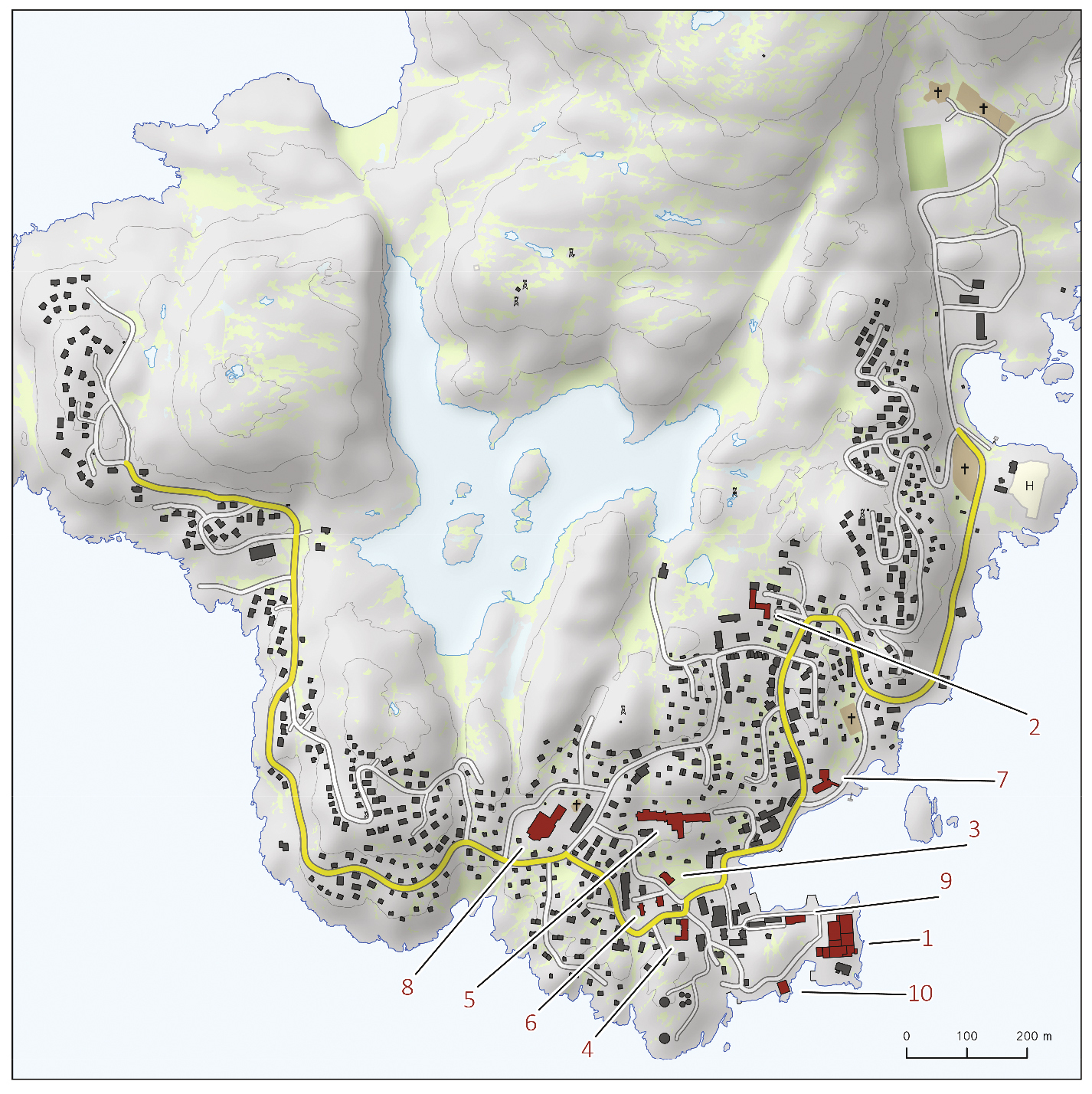

Uummannaq is a very hilly town with steep roads, which can impede traffic. The vast majority of dwellings are single-family homes, a good proportion of which have running water, while the other households pick up water at tapping houses or have it delivered by tanker. For most dwellings with running water, drains have been established for grey water from the bathroom and kitchen, while in general for the town there is no sewer system for black water from toilets. Thus, most households use toilet buckets and collection of latrines, while some have a sludge tank.

The evacuation of Nuugaatsiaq and Illorsuit has brought significant construction activity in recent years, mainly in the town’s northwest end, where the municipality plans future urban development.

In 1999, an airport was established at the settlement of Qaarsut on the Nuussuaq Peninsula, forming the south side of Uummannaq Fjord. From Qaarsut there is a helicopter link to Uummannaq and the district settlements. The intention was to improve the air service to Uummannaq that had until then been based on helicopter from Ilulissat, and Qaarsut was chosen due to more stable wind conditions and better space than on Uummannaq Island. It has since been debated whether the airport at Qaarsut has effectively improved or impaired air service between Uummannaq and Ilulissat.

Uummannaq receives supplies by ship from the Royal Arctic Line, allowing the town to export Greenland halibut every week from mid-May to mid-December. The first and the last ship may risk cancellation due to ice. In 2019, a restoration of the town’s quayside facilities and an expansion of areas for the stores of the fish factories were initiated. In order to improve the conditions of dinghy fishermen, a breakwater is planned in what is known as Smørhavnen.

In addition to the necessary supply such as a shop, power plant, waterworks and telecommunications, Uummannaq has a hospital, a school that also teaches the children of the settlement in the graduating classes, and a boarding house for school children, as well as an orphanage that accepts children from all over the country.

Trade and industry in Uummannaq

With approximately 300 commercial hunters, most of whom have fishing as their primary activity, fishing and fish processing is the district’s main industry and source of income. During the season, there are about 50 employees in the Royal Greenland factory, and somewhat fewer in the factories of Avannaa Seafoods and Sigguk Uummannaq ApS in Uummannaq. A similar number of people are employed in factories in the settlements. The Greenland Institute of Natural Resources in Nuuk estimates that fishing pressure in the district is above the sustainable level. A contributing cause is that some fishing vessels come from southern districts and fish on the Uummannaq quota.

Some jobs in Uummannaq can be found in administration and service and, to a lesser extent, building and construction. Growing tourism contributes ever more jobs both in summer and in winter, with dog sled tourism in particular attracting travellers. Local businesses offer accommodation for 40‑50 people in lodging houses and flats. The town has a supermarket near the port as well as two convenience stores and a third under construction in the northwestern part of the town. Nightlife is centred around the bar called Parabolen.

Further reading

- Avannaata Kommunia

- Hunting and subsistence economy

- Ilulissat

- Industry and labour market

- Infrastructure

- Qaanaaq

- The Greenlandic insular community

- Towns and settlements

- Upernavik

Read more about the Municipalities and towns in Greenland