KELD NAVNTOFT/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2009

In a referendum held in Greenland on November 25, 2008, with a turnout of 71.96 %, a majority of 75.54 % voted in favour of the introduction of self-government. With this, the Folketing adopted the Act on Greenland Self-Government to take effect on the National Day on 21 June 2009. The term ‘Self-Government’ is colloquially used in several ways. This includes the Self-Government Act that established the transition from home rule to self-government. Self-Government can also refer to the central administration, Naalakkersuisut (government), the political system consisting of Inatsisartut (Parliament) and Naalakkersuisut and/or the entire Greenlandic public sector. Thus, reference can be made interchangeably to aspects of constitutional law, organisation of administration or governance – or to self-government in more abstract terms. In Greenlandic, Namminersorlutik Oqartussat is used officially, meaning literally ‘those who govern themselves’, but the word for authority (pisortat) is also used to refer to the public sector.

BRODDI SIGURDARSON/UNITED NATIONS, 2018

Self-Government is very much a continuation of home rule and the institutions created and developed since 1979. But the Self-Government Act marks a development that makes Greenland one of the autonomous areas with the widest competences and self-determination in the world, without being formally sovereign. The Self-Government Act, uniquely for Danish legislation, as a preamble – a short, introductory text. This essentially acknowledges and redefines the population of Greenland as a people under international law with the right to self-determination. Since World War II, and the worldwide decolonisation, international law developed under the auspices of the United Nations but it was not until 2009 that Greenlanders became recognised by Danish law as a people in their own right.

Status as a people under international law is a condition for secession and state formation, and the Danish acknowledgement followed decades of work on the rights of indigenous peoples under the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) and UN auspices. Under the law, a referendum in Greenland, where a majority votes for independence, can start the process towards an independent Greenland.

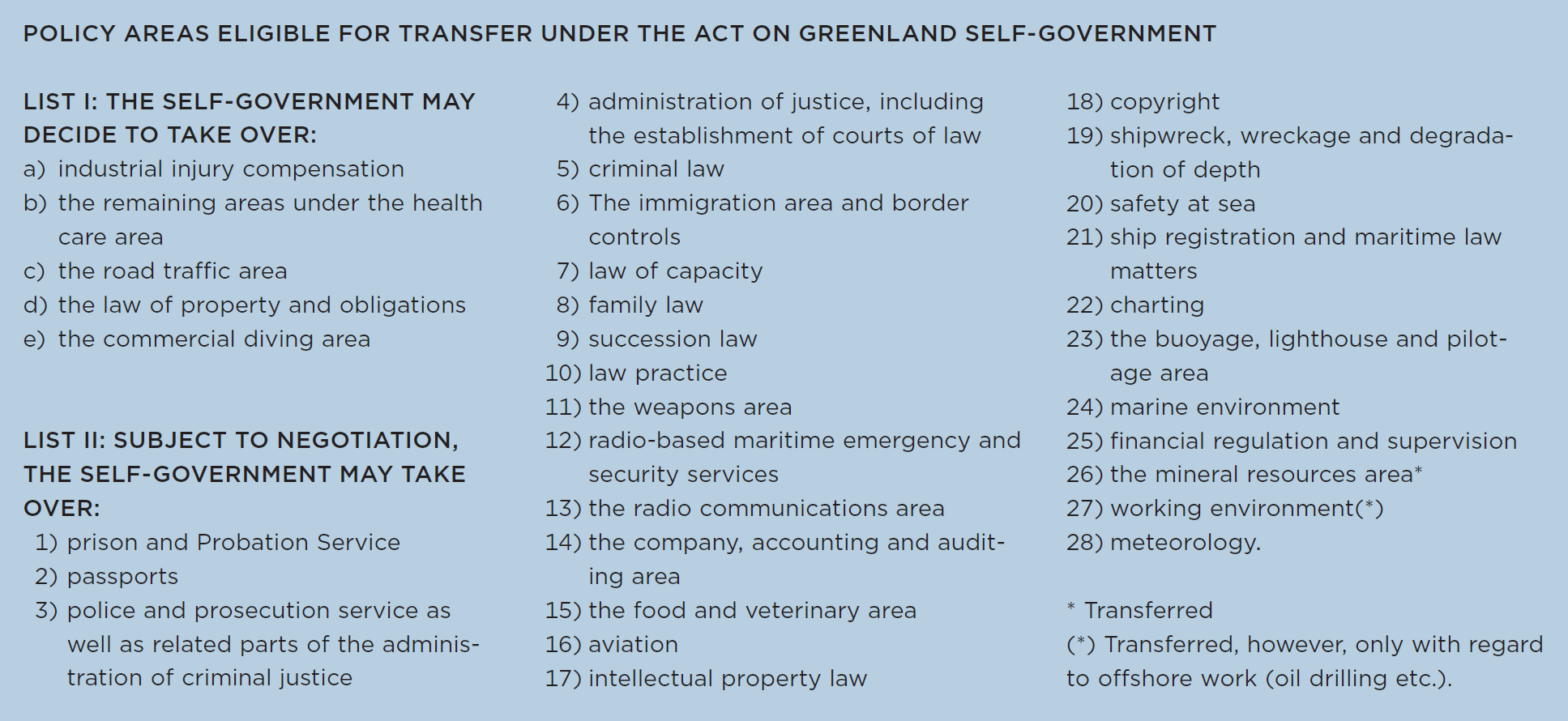

Furthermore, the Self-Government Act states that Naalakkersuisut and the Danish government are equal parties and that Greenlandic is the official language of Greenland. With the Self-Government Act, Greenland was allowed to take over a number of new policy areas which could not be taken over under the Home Rule Act. However, unlike the takeover of policy area under the Home Rule arrangement, financial resources are not included in the form of increased block grants from Denmark. While the areas allowed to be taken over under the Home Rule Act were taken over sooner than expected, the process has been slower under the Self-Government. Shortly after the introduction of Self-Government, one and a half area was transferred, namely part of the occupational health and safety area (offshore work) and the management of the mineral resource area, as the ambition was for extraction of mineral resources to be a significant step towards a self-sustaining economy.

The first chapter of the Self-Government Act establishes the tripartition of power, placing legislative power with Inatsisartut (Parliament), the executive power with Naalakkersuisut and the judicial power with the courts (which are so far under the jurisdiction of the state). The vast majority of legislative work and governance concerning Greenlandic affairs takes place under the auspices of Inatsisartut and Naalakkersuisut. However, including policy areas not yet transferred, the separation of powers is more complicated, since Inatsisartut and Naalakkersuisut are systematically involved in special legislation adopted by the Folketing for Greenland when national legislation is put into force for Greenland, and by international agreements of special significance for Greenland. In relation to foreign policy and the relationship between Danish and Greenlandic law, a number of grey areas remain. Although the Danish Constitutional Act describes a unitary state, the Unity of the Realm has some features that are more reminiscent of a federation. The political system has developed since the 1970s, and although Greenland is a relatively young democracy, the institutions are stable.

The electoral system

CHRISTIAN KLINDT SØLBECK/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

The 31 members of Inatsisartut are elected for a maximum term of four years. The turnout at Inatsisartut elections has remained stable at 70‑75 % in this century, but fell to around 66 % in the April 2021 elections. Interest in national politics is somewhat higher in terms of turnout than in municipal elections (approx. 60 %) and Folketing elections (approx. 50 %). All of Greenland forms one constituency in Inatsisartut elections, and the electoral system aims at proportionality, so that a party receives approximately the same proportion of mandates as the proportion of votes at the national level (specifically, the d’Hondt method of proportionate distribution of mandates is used). There is no formal minimum percentage of the votes necessary for a party to be represented in parliament, but a mandate costs about 1,000 votes or 3 % of the total votes. The system encourages voters to distribute mandates across quite a few parties, as known from multi-party systems in Scandinavia, among others. In the last few elections, the proportion of women who were elected directly has fallen to about 30 %, but the figure fluctuates quite a bit during each term, depending on which alternates are called upon.

On each party slate, candidates are nominated equally, i.e., the party mandates are awarded to the candidates who obtain the most personal votes, and not by priority party list. The votes for each party often gravitate towards a single vote catcher. He or she thus gets votes for not just his or her own seat, but carries one or more colleagues. The result is that a number of politicians are elected to Inatsisartut with quite a few personal votes (e.g., just over 50 votes were enough to be an alternate after the 2021 elections). In this way, it can appear somewhat random whether it is one or the other who is assigned a mandate – which you might then take with you if you change parties. Compared to other countries, far more people vote for a specific candidate rather than for a party at large.

Alternates are quite often called upon, for example, if a member asks for leave from Inatsisartut after being elected to Naalakkersuisoq (minister), the Folketing or municipal council, in connection with international delegation trips, sick leave or emigrating from Greenland. Dual mandates with a seat in both national and municipal politics or the Folketing are widespread, but often up for discussion, and it varies over time whether or not the respective parties allow dual mandates.

Originally, the Inatsisartut elections act ensured broad geographical representation in that eight districts were guaranteed one or more seats. One of the main arguments for amending the act with effect from 1999 was that less local politics was wanted in national politics. Instead, Inatsisartut was to take its cue from the overall interests of the country. That purpose has not been fully achieved. Looking at the candidates’ personal votes, many have a clear geographic base. Debates, negotiations and decisions are still to a certain extent characterised by local issues and regional interests, not least in relation to infrastructure and the fishing industry. A change to the electoral system is regularly proposed by different parties, for example by reintroducing local constituencies.

The party system

CHRISTIAN KLINDT SØLBECK/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2018

The three old parties of the 1970s were traditionally relatively easy to pinpoint ideologically: Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) far left, inspired by antiimperialist movements with Marxist rhetoric. Siumut was the broad social democratic people’s party. The conservative-liberal Atassut was the moderate party, both in terms of economy and in relation to Denmark.

Over time, three features have characterised the evolution of the party system. Firstly, the IA has gradually grown from a marginal position – both in terms of size and political content – to being equal to Siumut as a party fit to lead government. Secondly, the big right-of-centre party, Atassut, has lost some voter appeal. The ideological place and voter base are largely taken over by Democraatit (Democrats). Thirdly, over the years, a number of new parties have been launched, at times based on local interests or personal projects.

CHRISTIAN KLINDT SØLBECK/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

Most new parties have had limited lifespans, others have managed to take root. A number of breakaway members from existing parties have created new ones, several of which are based on fundamental features of the Siumut movement, such as Nunatta Qitornai (NQ) as the party of the big plans and a lot of show and Naleraq (N) as the party of the little man, fishermen and hunters. The social liberal Demokraatit was also originally founded by a breakaway member from Siumut, while Suleqatigiissitsisut (the co-operative party) was formed by former members of the Democrats about 15 years later.

No party has ever managed to become elected again if first voted out of Inatsisartut. In the 2018 elections, as many as seven parties were elected, but the two newest failed to become re-elected in 2021.

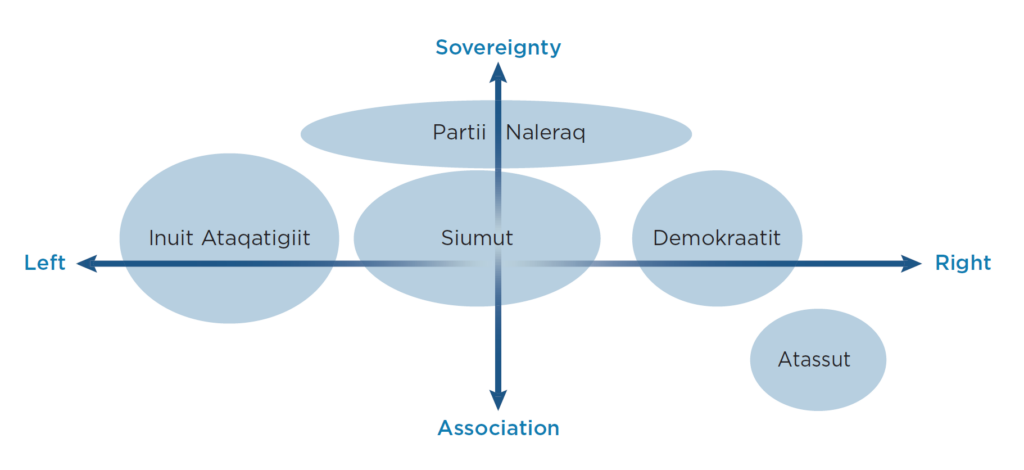

The figure shown below gives an overview of the Greenlandic party system, although complications in terms of both the axis of independence and the rightleft axis make it difficult. In terms of the axis of independence, most of the parties have a spectrum of views, and most of the parties have moved over time. IA has gone from being a secessionist party to underline the value of a close pragmatic relationship with Denmark, like in other formal forms. For some periods, Siumut has been busy distancing itself from Denmark, but at all times, the party has also included politicians taking a pragmatic approach. Most recently, Atassut has returned to its original starting point as a proponent of the Unity of the Realm, after a number of years as a supporter of independence. Demokraatit has moved toward independence, only with considerably less haste than Naleraq.

In terms of the right-left axis, there are several newer parties that designate themselves as social liberal and are advocates of privatisation or a smaller public sector. Arguments for a smaller public sector, however, also exist on the left wing. For some parties, privatisation means selling large public monopoly companies to private investors (in practice mainly foreign companies due to lack of Greenlandic capital). For others, it means dissolving monopolies to make way for small local initiatives. Several parties talk about redistribution to address economic inequality, but some emphasise reducing regional inequality, others want to prioritise settlements and small towns, and again others have the unskilled and underemployed in the concrete blocks of towns in mind. Siumut has recently started to move back towards the left and Atassut simultaneously towards the right, while Naleraq’s original starting point focusing on hunters and fishermen in recent years has been complemented by more liberal politicians and ideological thinking. The IA and Democrats have more urban voters, while Naleraq and Siumut voters are found in smaller settlements along the coast. Atassut was formerly a Nuuk party, but now primarily picks up votes in towns such as Ilulissat and Maniitsoq.

RASMUS LEANDER NIELSEN OG ULRIK PRAM GAD, 2022

Coalition formation

EMIL HELMS/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

After the April 2021 elections, for only the second time in Greenlandic political history, IA could take the post of premier of Naalakkersuisut. And in 2022, Siumut entered for the first time as a junior partner in a coalition. Siumut has otherwise sat almost continuously as the leading party since the birth of the party system in the 1970s. Siumut has formed coalitions with ideologically very different parties and has frequently switched coalition partners several times during a parliamentary term. Siumut, as a broad popular movement, has been home to many political currents, local interests and strong personalities. The premier of Naalakkersuisut and the leader of Siumut has most often been one and the same person, and often premiers have had almost the same amount of work keeping their own party together as they have had for their coalition partners. Coalition breakdowns happen relatively often as a result of political disagreements over concrete issues, matters of principle or shifting balances of power internally within Siumut – or as a result of one of the smaller parties having lost patience with Siumut’s leadership, course or lack of the same. Most governments have been based on majority coalitions; however, there have been minority governments in the 1980s and for most of the 2018 – 2021 parliamentary term.

A settled tradition has developed in which post-election coalition formations or government transformations are accompanied by more or less verbose political coalition agreements. However, large parts of the documents consist of adherence to unspecified ‘reforms’ in different areas or unprioritised ‘priorities’ in a wide range of areas. Large parts of the text can therefore be the same from one government base to the next, or as in the parties’ election campaign materials. At the same time, coalition talks are concentrated on matters high on the current political agenda and on seats in Naalakkersuisut, committees and the boards of the government-owned companies. In these texts, parties may also explicitly agree to disagree if a policy area creates a conflict dimension that otherwise cannot be resolved – e.g., in relation to mining involving the extraction of uranium.

Based on international coalition research, one would expect coalitions to be formed by parties with the least possible ideological distance. However, this has far from always been the case in Greenland. Most spectacular was when in 2009 the socialist IA and liberal Demokraatit joined forces, not least to exclude Siumut. Following on from the movements of the parties on the axis of independence and the differing emphasis the parties place on various economic issues, only very few party combinations have seemed impossible in the self-government era.

Parliamentary practice

CHRISTIAN KLINDT SØLBECK/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

As in other parliamentary systems where government springs from the legislature, Inatsisartut balances between two roles in relation to Naalakkersuisut: On the one hand, it is necessary for Naalakkersuisut to be backed by its majority in Inatsisartut, otherwise no political decisions and legislation would be made. On the other hand, Inatsisartut must make sure that Naalakkersuisut acts according to the rule of law. Inatsisartut may eventually enact a vote of no confidence and thus remove Naalakkersuisut if it does not comply with the law.

In the first – legislative – role, members act primarily as party members and thus as either opposition or as the parliamentary base of the government. In the second – monitoring – role, the members ideally act as a unified body to control the government, disregarding party lines. In practice, the political game often plays out more complexly: Naalakkersuisut does not agree with its parliamentary base on policy. Or the Inatsisartut members identify themselves rather as party soldiers than as a control body and tend to stick up for a minister whose acts seems to be at odds with the law. No-confidence motions have periodically been a frequently used tool when the opposition, as well as at times members of government parties, have disagreed with the policy pursued. Particularly in a number of cases involving the misuse of public funds for personal consumption, a number of Naalakkersuisut members have had to resign, directly or indirectly as a result of parliamentary oversight. Early elections may be called by a majority of Inatsisartut by law. The incumbent premier of Naalakkersuisut can only call an election if a majority of Inatsisartut has passed a vote of no confidence in him or her, or by tabling a bill which must then be passed by a majority.

Both the legislative and supervising role of Inatsisartut are undertaken primarily when in session, secondarily in committees. Meetings in the chamber are traditionally held during a spring session and an autumn session, where, among other things, the Budget for the following year is adopted. Extraordinary sessions may be needed for various reasons.

According to law, Inatsisartut is required to establish a number of permanent committees: The Scrutiny of Eligibility Committee, the Legal Affairs Committee, the Finance and Fiscal Affairs Committee, the Audit Committee and the Foreign and Security Policy Committee. In addition, a number of special committees are formed to discuss issue-specific legislation, etc. on behalf of the entire Inatsisartut and any ad hoc committees, e.g., one to follow the work of the Constitutional Commission, for example. Parties are formally allotted committee memberships proportionately (again following d’Hondt’s method), but in practice parties can negotiate for seats on the committees they prefer.

Legislation is negotiated in three plenary readings; each of the two first readings may refer a bill to one or more committees. Motions for resolutions other than legislative amendments are most often considered in two plenary sessions and possibly in a committee. Important or controversial matters are often negotiated by one or more members of the Naalakkersuisut directly with representatives of parliamentary party groups in between the formal proceedings. Major reforms are often prepared in commissions with representation of interest organisations and experts carrying out investigative work and/or providing recommendations, not least if political disagreement makes it opportune for the governing coalition to kick the matter to the corner.

In order to attend to important areas of its control function, Inatsisartut appoints an ombudsman to whom citizens can complain about the administration’s specific proceedings and decisions. Inatsisartut’s control over the expenditure of the national treasury is carried out through the Audit Committee, while the auditing of the national treasury accounts is carried out by a private firm of auditors. Generally, the Danish Public Accounts Committee does not deal with the finances of the Self-Government, other than ascertaining whether the Danish block grant has been properly transferred. Inatsisartut and the committees are given secretariat assistance by the Bureau for Inatsisartut; in addition, the national treasury funds secretariats for the party groups and also provides grants for election campaigning. There is regular criticism from the Inatsisartut Committee that information provided by Naalakkersuisut is deficient and/or delayed in relation to both the legislative work and the control functions of Inatsisartut.

A number of matters weaken the continuity of special committee work and, more seriously, popular confidence in the political system. Frequent coalition reshuffles trigger reconstitutions of committees each time a member of Inatsisartut is appointed to Naalakkersuisoq. Similarly, a game of ‘musical chairs’ is triggered when a politician switches from one party to another. For example, in 2018, a member of Naleraq defected to Siumut just a few weeks after the election. Before the same election, Atassut had lost both of his mandates due to party defections, so the party had to collect signatures to become eligible again. The frequency of such party defections in Inatsisartut and municipal politics has led to suggestions that a mandate be locked to a party, not individual politicians. Similarly, ‘dual mandates’ is an ongoing theme in several parties: Is it a strength for his or her political work that an Inatsisartut member has a seat in the Folketing or a municipal council at the same time, or is it prohibitive for tending to the work with due care? The two problems become entangled when a dual mandate prevents a party defector from taking over the seat as an alternate.

The tone of the public political debate in Greenland can be fierce, both on social media and in the commentary track on online media articles, but also in regard to debates in Inatsisartut. A number of Naalakkersuisut members and party chairpersons have had to take sick leave due to stress. Several significant profiles have left politics citing the personal costs. At the same time, there is a demand for local talent which makes it easy for particularly younger and well-educated people to switch career tracks from politics.

Economy and governance of the Self-Government

EMIL HELMS/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2021

The disadvantages of the insular community and welfare ambitions means that Greenland has a large public sector with a number of centrally planned economic features. There are several reasons for this. The task of Self-Government is to run a welfare state, partly inherited from the Danish model, for a very small population spread over a very large territory.

To a wide extent, the disadvantages of the insular community become primarily relevant due to the ambitions of the Self-Government. Welfare, settlement pattern and self-government are conditions for the Self-Government’s task solving given by the voters. Consequently, considering the size of the public sector there are two ways forward: developing the business sector and prioritising the service level in different areas so that revenue and expenditure can balance. And to organise the administration and organisation of the public sector most effectively in relation to the needs and conditions of society. Here, the political focus has often been directed at inappropriate structures that have been taken over from the Danish colonial administration.

RASMUS LEANDER NIELSEN OG ULRIK PRAM GAD, 2022

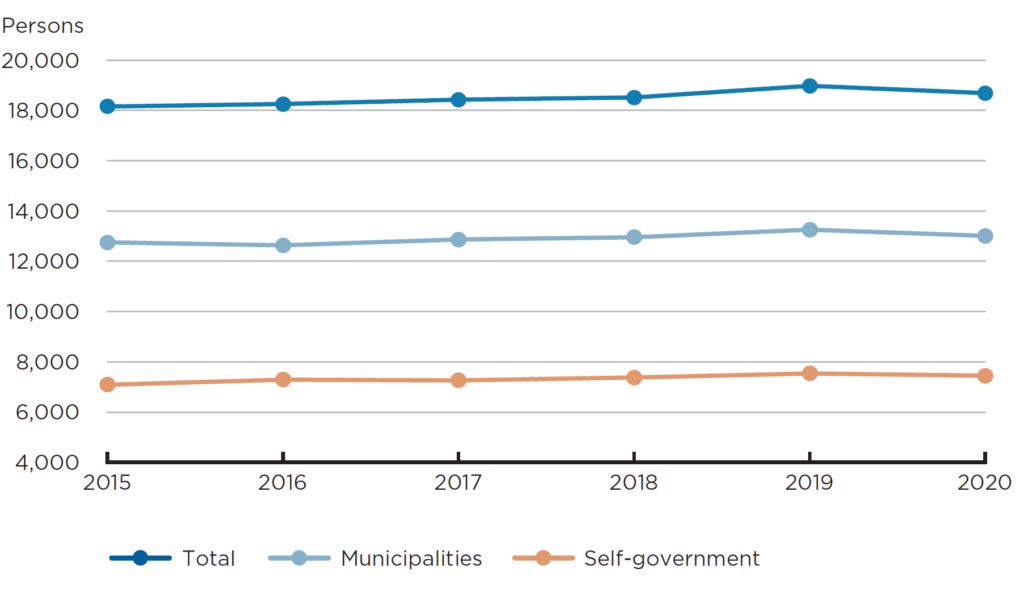

Total public expenditure is around 60 % of the GDP and around 40 % of all employed persons are employed in the public sector, including management, education, health and social services and institutions. In total, just under 19,000 people work in the public sector. If only full-time employees are included, in 2019 there were well over 11,000 full-time employees in the public sector, of which just over 4,000 are full-time employees in the Self-Government and well over 6,800 in the municipalities.

As regards the economy of the Self-Government in the strictest sense of the word, economists have identified an ‘abyss’ between developments in the treasury’s revenues and expenditure driven by, on the one hand, uncertainty about the sources of revenue and, on the other hand, increased demand for welfare services. According to the Greenland Economic Council, all else being equal, the expenditure will increase corresponding to 5‑6 percentage points of the gross domestic product, in line with a growing number of elderly people in the population. However, there is uncertainty about whether future generations will work longer into old age by virtue of better health, as well as the proportion of elderly people who require most care who would prefer their old age in Denmark. Up to and including 2008, the retirement age was 63, in 2009 it was extended to 64, in 2010 to 65. In 2017, the retirement age was further increased to 66, and in 2021 to 67.

Government revenues follow economic trends, especially in the fishing sector. The block grant of just under DKK 4 billion and other expenditure incurred directly by the Danish State means that both private and especially public revenues and consumption opportunities are greater than that generated by the domestic production of goods and services. Similarly, compared to many other countries, the Greenlandic economy is less threatened by, for example, financial crises and pandemics, as the block grant acts as a buffer against external economic shocks and as a safety net for international borrowing.

In the same way as under the Home Rule Act, the block grant is continuously regulated in accordance with price developments in Denmark, but under the Self-Government Act, increased block grants are not included when new functions are taken over from the state. Any revenue from the mineral resources area (corporate taxes, royalties, etc.) exceeding DKK 75 million is divided equally between the Self-Government and the Danish State by reducing the block grant with the Danish State’s share. In addition to revenue from taxes and duties, the treasury has revenue in the form of dividends from government-owned companies, the profits of which, however, may have been generated by publicly paid service contracts or politically approved tariffs/prices.

In recent years, there has been a boom in macroeconomic activity, mainly due to favourable export fish prices representing more than 90 % of total exports. This has led to a strengthening of the general government revenue and profit on the government finances.

A comparison of the industries’ share of the total production in 2020 shows that the industry of ‘public and personal services’, consisting of the production of public services for administration, health and education, is the largest industry and represents almost one third of the society’s production. ‘Fisheries, hunting and industry’ (including the fishing industry’s factories) together account for 20 % of the production and the ‘construction industry’ accounts for around 14 % of the total production and is thus the third largest industry.

As far as the public sector is concerned in the broader sense, there is a recurring desire from politicians, Greenland Business Association and the Economic Council, among others, that it should be slimmed down. A key argument is that increasing efficiency in the public sector would free up labour and thus the opportunities to develop private industries. In order to become less dependent on external transfers and fluctuations in stocks, quotas and market prices in fisheries, efforts are being made to diversify the economy, primarily by promoting mining and tourism.

Organisation of public administration

MARTIN LEHMANN/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2019

The public administration consists of the Self-Government, the municipalities and the institutions of the state. The Self-Government executive branch is headed by Naalakkersuisut. The task of the central administration is to serve, advise and ensure that Naalakkersuisut makes decisions based on an informed basis, as well as to implement political decisions and administer within the framework of legislation adopted by Inatsisartut. Typically, a Naalakkersuisoq (minister) has several portfolios and accordingly the responsibility for several units of the central administration. Mostly, the central administration has been organised into about 10 cabinet departments, slightly fewer executive agencies, and as number of decentralized units. Over time, core government responsibilities reappear in various combinations, such as finances, fisheries, education, infrastructure, business, health, social affairs, etc. Other portfolios are established in order to secure or signal special political attention areas and may have relatively short lifespans, such as settlements and outlying districts or independence. Departments primarily support the political role of their respective naalakkersuisoq in relation to the legislative process and negotiations, while executive agencies work within a specified set of rules with specific decision-making powers delegated. Decentralized units undertake similar tasks where close citizen contact is important, as well as tasks that are of an operational character.

Spread over nine floors in what is known as the Self-Government Tower in Nuuk Centre, one or typically several departments work on each floor. The premier’s department, however, remains in the old administration building on the other side of the pedestrian street in Nuuk, where the Inatsisartut chamber can also be found. Sizeable sums are spent on reorganisation, interpretation and recruitment. In key ministerial posts (e.g. fisheries), major replacements and new coalition formations mean that departments move to another floor in the Self-Government Tower to gather newly combined portfolios under the same minister. Despite recurring demands to slim down the public administration, several functions under Naalakkersuisut appear to be understaffed compared to the ambitions of the given government coalition. The shortage of educated Greenlandic labour demanded by the departments (typically lawyers and economists) leads to the recruitment of of a steady stream of new Danes, often imported shortly after having received their diplomas. An ongoing theme in the political debate is how formal education should be weighted in relation to practical experience and Greenlandic language skills. Much locally recruited as well as imported labour seem to prefer employment in private or government-owned companies where the pay is higher and the distance to daily politics is longer. Each year, an amount in the millions is spent on external consultancy services in the departments and underlying institutions of the Self-Government. If new areas are taken over from the Danish State, it will create additional demand for qualified labour.

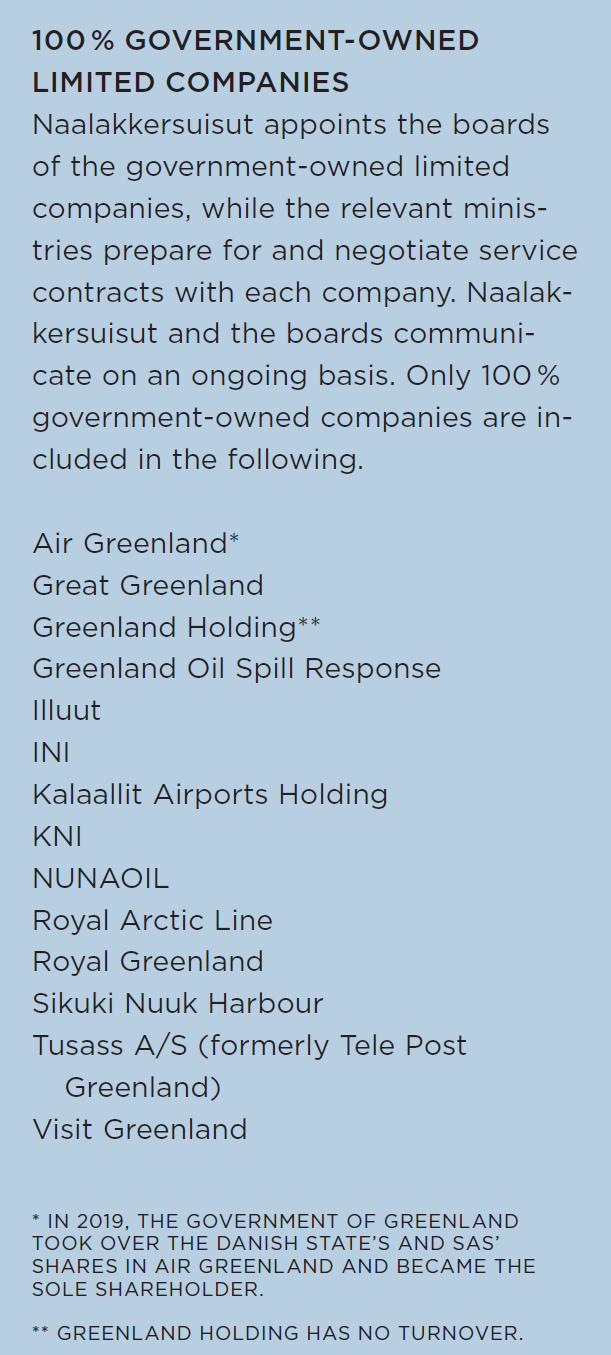

Operations of as well as construction works relating to public services are to a large degree organized in government-owned companies. The companies’ activities include traditional public areas of activity, such as infrastructure and utilities, as well as business activities in fishing, shipping and retail, which in other countries are more widely left to the market. Overall, the government-owned companies are organised as either net managed enterprises (Asiaq, Mittarfeqarfiit and Nukissiorfiit) with public subsidy grants or in limited liability company form where some of the most important include Great Greenland (sealskin products, etc.), Greenland Holding (business promotion), INI (housing), Kalaallit Airports (airports), KNI (e.g. retail), Royal Arctic Line (shipping), Royal Greenland (fish and shrimp), Tusass (formerly Tele Post Greenland) (tele and postal services) and Visit Greenland (tourism). The majority of the government-owned limited liability companies are 100 % owned by the Self-Government, but in a few companies, government holds only a minority share, (e.g., Grønlandsbanken).

The tasks of the municipalities

FILIP GIELDA/VISIT GREENLAND, 2019

The municipalities carry out a range of civic tasks such as the operation of day care centres, schools and nursing homes, the social area (with the exception of 24-hour institutions), local engineering and environmental management, and local business development. The Self-Government Act does not provide precise provisions on the division of tasks between the Self-Government and the municipalities, but municipal autonomy is provided for in Section 82 of the Danish Constitution. Municipal tasks are attended to on the basis of delegation and decentralisation of tasks adopted by Inatsisartut in the relevant legislation or, within the framework of current legislation, by Naalakkersuisut.

The Local Government Act establishes, among other things, that the municipal committee structures and the tasks of committees, budgetary processing, the tasks of the administration and the supervision of the municipalities as described in Inatsisartut Act No. 22 of 18 November 2010 on the Administration of Municipalities. The rules governing municipal government defines in terms of municipal law what the municipalities may use their funds for in order to meet the general needs of the local community. The Self-Government negotiates block grants with the municipalities every year.

Municipalities before 2009

In 2009, a major structural reform was implemented in Greenland. The history of Greenlandic municipalities can be traced back to 1857 when governorships were created on a trial basis. In 1908, municipal councils (62) were introduced with the Act on the Government of the Colonies in Greenland of 27 May 1908, but the scheme did not come into effect until 1911. At the same time, two provincial councils were introduced and the governorships were discontinued. The municipal councils were tasked with poverty assistance, support and care for public order as well as paying expenses for the common benefit of the municipality.

In 1950, the Act on Greenland’s Provincial Council and Municipality Councils was introduced. The 16 municipalities in West Greenland (Thule and East Greenland were not included until the 1960s) took over some of the tasks that had previously been under the colony administrators, including roads, bridges, refuse collection and fire services. The municipal reform of the mid-1970s involved a transfer of some state areas of responsibility to the municipalities and thus a changed distribution of duties and responsibilities, including the local treasurer function and the right to determine municipal income tax. In 1994, the white paper from the Local Government Reform Commission became the basis for a new governance regime for the municipalities and the additional transfer of tasks to the municipalities from the Home Rule Government.

The mandate of the structural committee from 2003 was to assess the advantages and disadvantages of various models for a changed distribution of duties and responsibilities in public administration. On the basis of the different models, the commission was to carry out an assessment and submit proposals on the geographical and population criteria, including what municipality sizes should form the basis for a future municipal structure. The main features of the structural reform were that the Home Rule Government and since then the Self-Government should primarily carry out legislative and supervisory tasks, and that the municipalities were given more operational and construction tasks. In order to implement the increased task volume, municipalities had to be merged into larger entities.

Municipalities after 2009

ANINGAAQ R. CARLSEN/VISIT GREENLAND, 2019

Prior to 2009, the elected assemblies of a Inatsisartut (Parliament), consisted of 18 municipal councils and 56 settlement councils with more than 380 elected officials. Following the structural reform, the elected assemblies were reduced to the Landsting (Inatsisartut) and four municipal councils; less than 100 elected officials. Small towns or local areas are assured a seat on municipal councils, and only parties that nominate candidates there, can win these mandates.

The structural reform entailed the revising of a number of executive orders, circulars and regulations in order to reduce micromanagement and to ensure more efficient case handling. The purpose of the simplified legislation was to ensure greater transparency in terms of requirements, rights and competences of the Home Rule Government, municipalities and citizens. The structural reform transferred tasks worth around DKK 1 billion from the Home Rule Government to the new regional municipalities. By decentralising the tasks, rationalisation gains of around DKK 200 million annually could be achieved. This analysis, however, is not supported by subsequent economic impact analyses.

AQQALU AUGUSTUSSEN/KIVITSISA, 2020

The Structural Committee recommended that there should be at least 8,000 inhabitants in each municipality and proposed a merger of the 18 municipalities into the following four regional municipalities: Qaasuitsup Kommunia, Qeqqata Kommunia, Kommuneqarfik Sermersooq and Kommune Kujalleq. Following a referendum in 2018, a division of Qaasuitsup Kommunia into two municipalities was carried out: Avannaata Kommunia and Kommune Qeqertalik. Thus, there are currently five municipalities in Greenland.

The areas that were actually transferred in the connection with the structural reform were the establishment of a common citizen service portal, the centralisation of the tax and debt collection area, the transfer of planning authority to the municipalities, the transfer of pedagogicalpsychological advisory services, extensive remedial instruction and the disability area and the centralisation of business support schemes.

The other areas were not transferred to the municipalities, including responsibility for negotiating service contracts on the supply of goods, shipping and airline traffic, electricity, heating and water supply, ports, the housing and construction areas. In addition, the health areas such as alcohol abuse treatment, health care and parts of the prevention area as well as a number of operational areas in the field of education were also not transferred to the municipalities. Finally, the pension area, maternity benefits, rent subsidy, child allowance, 24-hour care centres and alimony continued to be administered centrally.

A recurring theme is how a better division of competences between municipalities and the Self-Government is ensured. Decentralisation is often an electoral theme involving discussions about the future of the municipalities — possibly in new municipalities or a return to past divisions. Historically, an institutionalised cooperation has existed across municipalities through the KANUKOKA (joint municipal cooperation organisation) which has, however, been discontinued, and a new coordinating body has not been established to replace it.

The large geographical spread and low population combined with the desire to maintain a welfare society makes the public administration relatively large, also at the municipal level. At the same time, it means that the municipal room for manoeuvre and the avenues of action for the municipalities become highly dependent on key national political decisions on the placing of infrastructure, the placing of public enterprises, educational institutions, etc.

KANUKOKA was formed in 1972 as a joint municipal cooperation organisation for the purpose of attending to the common interests of the municipalities in negotiations and to provide advisory services and assistance to member municipalities. In 2016, Kommuneqarfik Sermersooq left KANUKOKA and the other three municipalities decided to move the head office from Nuuk to Maniitsoq. In 2018, the member municipalities decided to dismantle KANUKOKA and find other ways for the municipalities to work together.

The political coordination group, consisting of Naalakkersuisut and the five mayors, still cooperate. The group meets two to three times annually to deal with inter-authority issues and common public issues.

The municipalities still cooperate regularly, for example, in 2017 the five municipalities cooperated to raise the level in primary secondary schools through the Kivitsisa project (»Let’s elevate«). This cooperation is unique as it is the first time that all municipalities join forces to develop primary schools. Here, they have joined forces on a project to develop the teachers, the teaching and the learning methods using e.g. technology. An iPad project is partly fundfinanced (with DKK 50 million) and partly self-financed by the municipalities (with DKK 100 million). Since the start of the project, the project management has focused on upgrading the qualifications of teachers and extending of the installations in towns and settlements that will enable the use of iPads in education. The project is expected to be fully implemented by 2024.

Another example is the establishment of the national waste company, ESANI A/S, which was founded on 1 February 2019. The company’s main purpose is to create solutions for the treatment of all types of waste in Greenland. The board of the company was to have members from all the municipalities in the country. Ten months after its establishment, however, Avannaata Kommunia withdrew from the company as it wanted other local waste solutions for its settlements. Thus, the joint municipal cooperation projects are challenged by the very different natural geographical and socio-economic conditions of the various municipalities.

At national level, a forward-looking plan for new airport extensions primarily in Nuuk, Ilulissat and Qaqortoq (the airport package) has been adopted, as well as hydropower plants to supply Qasigiannguit and Aasiaat, among other things. In terms of mineral resources, a stop to oil and gas exploration and a prohibition on exploitation of minerals containing radioactive elements above a certain level have been introduced. This type of large-scale national political decisions has a considerable local impact on the municipalities’ room for manoeuvre, as it very much defines the business and employment opportunities of municipalities, the mobility between the municipalities as well as the revenue and expenditure of the municipalities.

Socio-economic players and social advocacy institutions

MORTEN RASMUSSEN/BIOFOTO/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2015

In addition to the administrative players under the Self-Government and municipalities, a number of societal institutions play prominent roles. This applies to key employee and occupational organisations, but increasingly also a quite unique construction with spokespersons for various vulnerable groups.

SIK

ULRIK BANG/RITZAU SCANPIX, 2007

The labour union SIK (Sulinermik Inuussutissarsiuteqartut Kattuffiat) dates back to the Greenland Workers’ Association, GAS, which was formed in 1956 but was given its current name in the late 1970s. SIK organises all unskilled workers and some skilled workers as well as various groups of students and trainees. The union has entered into a general agreement with employers, it is a negotiating party in connection with collective agreements and has historically worked for the elimination of the birthplace criterion, worked for equal pay and has been a formative party to a number of major reforms for the development of present-day Greenland. It also participated in the EC-critical ANISA in the early 1980s and was thus a factor in the withdrawal from the forerunner of the EU together with, among others, the Siumut and IA as well as KNAPK.

However, as the largest labour union, SIK has also been criticised for failing to ensure an acceptable level of pay for many of its members.

KNAPK

KNAPK (Kalaallit Nunaanni Aalisartut Piniartullu Kattuffiat) is the association for fishermen and hunters. KNAPK was founded in 1953 as a consolidation of local associations following a meeting between the KGH (Royal Greenland Trading Department) and the office of the Governor. KNAPK is headquartered in Nuuk, but has a number of local departments and councils for various species (shrimp, Greenland halibut and snow crabs, etc.).

The association works to develop the business of Greenlandic fishermen and hunters economically, societally and culturally. Conflicts of interest sometimes arise between the Department of Fisheries and Hunting and KNAPK, as well as SQAPK, which represents some of the dinghy fishermen in the Greenland halibut districts in North Greenland.

Sulisitsisut — Greenland Business Association

Established in 1966, Greenland Business Association (GBA) is Greenland’s largest business association. The association works to safeguard the interests of Greenland’s business community for both small and medium-sized enterprises to large corporations operating in international markets. GBA is organised into 10 industry committees and, as employer organisation, represents the vast majority of companies and the vast majority of private businesses. Together with SIK, it has also raised issues regarding social dumping and the challenges posed by foreign labour.

Every two years, GBA organises the Future Greenland conference, which attracts speakers and Danish top politicians and business professionals as well as international guests. However, it has also been criticised for failing to ensure that the conference adequately locally rooted in the Greenlandic community.

Social Advocacy Institutions

Up through the 2000s, changing governments have had an increased focus on social challenges in society. Advocates have been appointed in the area of children, disability and the elderly, respectively, to personify this key area and to let the individual politically independent advocate become the face of the focus area. Although all three institutions carry the name ‘advocate’, these are three widely different institutions. This applies in terms of powers, tasks, organisation, secretariat and budget grants.

In order to promote the rights and interests of children in society, and as part of implementing the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Greenland acceded to in 1993, it was agreed in 2011 to create a National Advocacy for Children Rights. Based on this, the MIO was set up in the same year, aimed at promoting children’s rights and interests. The National Advocacy for Children Rights consists of the Children’s Advocate, the Children’s Council and a secretariat. On paper, it is a politically independent institution, but it is Naalakkersuisut that appoints the Children’s Advocate and the Children’s Council. The Children’s Council advises the Children’s Advocate, who is responsible for employing secretarial staff. MIO works to translate the UN Children’s Convention into concrete initiatives that improve children’s everyday lives. The Children’s Advocate provides advice and guidance to children as well as to authorities, institutions, organisations and private individuals. In addition, the institution must monitor, disseminate knowledge, influence the public debate and make proposals for improving children’s conditions, and report to the United Nations on how Greenland is complying with the UN Children’s Convention. The Children’s Advocate travels all over Greenland to talk to children about their living conditions, after which reports are submitted to authorities and the public. In recent years, the Children’s Advocate has become a distinct voice in the public debate and has ensured children’s conditions a more prominent place on the political agenda.

As a result of Greenland acceding to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2012, Inatsisartut passed a law in 2017 establishing a National Advocacy for Persons with Disabilities. Tilioq was established in the same year and is to ensure the practical and citizen-centric implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The Disability Advocate is appointed by Naalakkersuisut and aims to promote rights and interests in society for persons with disabilities. Unlike the Children’s Advocate, Tilioq does not have an advisory council, but consists of the Disability Advocate and a secretariat. The Disability Advocate provides advice and guidance to people with disabilities and must also advise authorities and institutions and disseminate knowledge and influence the debate with proposals for improving the conditions for people with disabilities. Tilioq works to ensure that legislation and practices meet the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Through its work, Tilioq has since 2017 made it clear how difficult it is to live with a disability in Greenland.

In 2020, yet another advocacy institution was established, with Inatsisartut passing the law on a National Advocacy for the Elderly in 2019. Unlike the other two advocacy institutions, the National Advocacy for the Elderly is not based on a UN convention. Instead, the National Advocacy for the Elderly should be seen as part of Naalakkersuisut’s policy for the elderly. Unlike the other advocacy institutions, the National Advocacy for the Elderly neither has a council nor a secretariat, and is instead served by the secretariat of the National Board of Social Services. The duties of the Advocate for the Elderly are to ensure and promote the opportunities and interests of the elderly and to draw attention to and provide information about the conditions of the elderly in society. Although being an advocacy institution similar to MIO and Tilioq, it has been allocated no funds to ensure that it can meet its purpose to the same extent as the two other advocacy institutions.

Further reading

- Education

- Health and care

- Home Rule (1979‑2008)

- Housing

- Hunting and subsistence economy

- Industry and labour market

- Infrastructure

- Peqqineq – Health and balance

- Plans in Greenland

- Population and demographics

- Premiers of Naalakkersuisut 1979-2022

- The Continental Shelf Project

- The five regional municipalities

- The Greenlandic insular community

- The Unity of the Realm and the Danish State

- Towns and settlements

Read more about Society and business in Greenland