The first several years of producing films with Greenland as the theme, the productions were foreign, and the perspective was usually stereotyped and exotising. Both in feature films and documentaries, however, this focus has changed; where previously you saw Greenland from the outside, you now increasingly see the country from the inside. The focal point is no longer to the same extent colonial history; it has changed to general human experiences. After the turn of the millennium, a young Greenlandic film industry has flourished, and one of many ambitions is to create purely Greenlandic films.

The early years – foreign representation

SKANDINAVISK TALEFILM, NORDISK TONEFILM, NORRØNA FILM/DET DANSKE FILMINSTITUT, 1930

The first films shot in Greenland were foreign/Danish productions. Often they drew on exotic stereotypes of indigenous peoples or showed the country as a productive colony under Denmark. These documentaries aimed to present Danish sovereignty to audiences at home and abroad at a time when tensions with Norway were growing over territorial claims on the east coast of the island.

Two films produced from the early 1920s, Kongeparrets Grønlandsrejse (King Christian X and Queen Alexandrine visiting the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland) (1921) and Den store Grønlandsfilm (the Great Film of Greenland) (1922), a silent film about the Fifth Thule expedition 1921‑1924, led by Knud Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen, showed Greenland as alien, exotic and as a successful colonial endeavour.

Film history’s first feature film with Greenland as its theme was Walter Schmidthässler’s silent film Das Eskimobaby from 1918, starring Asta Nielsen as Ivigtut, who meets a young polar scientist, Knud, whom she follows to Berlin. The film thematises exotic Greenland versus Western culture and depicts Nielsen as a nature child who causes trouble in a philistine family. The film shows only sporadic familiarity with Greenland and is full of misguided stereotypes.

In 1930, Georg Schnéevoigt’s Danishproduced film Eskimo came with Norwegian/Greenlandic speech and with Greenlandic actors as extras, created on the basis of polar explorer Ejnar Mikkelsen’s novel John Dale (1921). The film stages Greenland as the country where you experience life as significant, purposeful and healing.

The Wedding of Palo

Paalup nuliarsarnera (The Wedding of Palo), which premiered in 1934, was the first East Greenlandic-language film. Knud Rasmussen wrote the script, the German documentarist Dr. Dalsheim was behind the camera.

The film is about falling in love and the road to marriage. The process is presented as more than a ritual, and it shows how those involved handle some of the conflicts that a wedding can bring about. At the same time, the film is an example of how Knud Rasmussen, through his commitment, found many ways, including the medium of film, to promote Greenlandic culture.

In The Wedding of Palo, Knud Rasmussen is assisted by the purely East Greenlandic cast, which, together with the stunning scenery, is what made the film succeed.

The film premiered three months after Knud Rasmussen’s death and thus became a memorial to him.

Documentaries

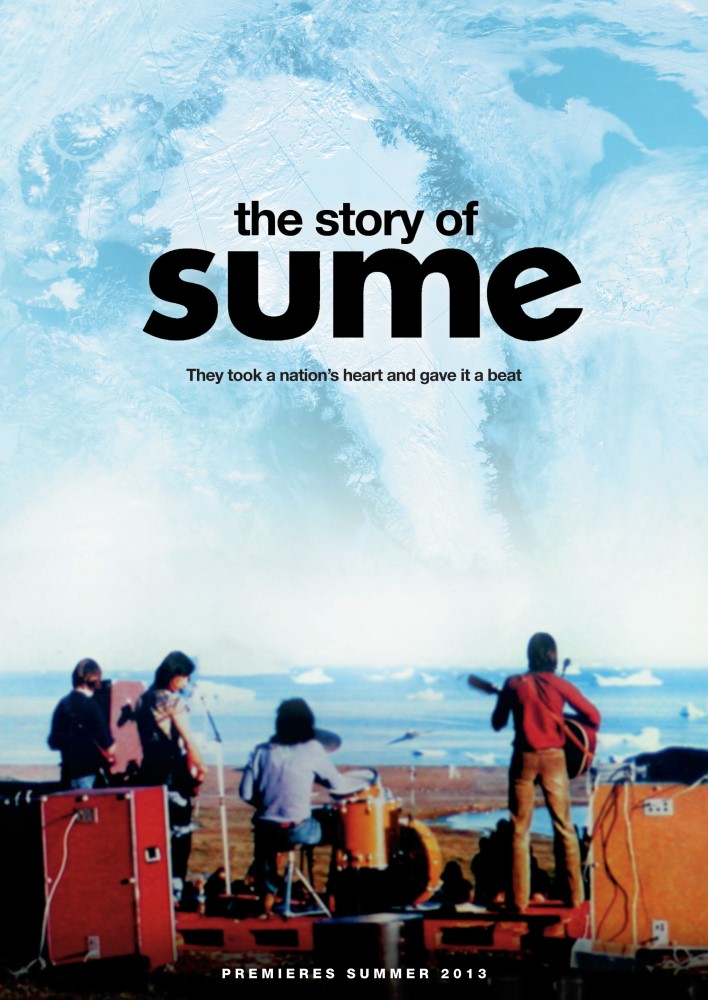

ANORAK FILM/DET DANSKE FILMINSTITUT, 2013

From the first short film, Driving with Greenland Dogs, by director Peter Elfelt, recorded in Fælledparken in 1897, many documentaries have been made by Danes about Greenland. In particular Jørgen Roos and his fascination of Knud Rasmussen and Greenland resulted in the Danes getting good knowledge of the country, not least with Per Kirkeby and Aqqaluk Lynge’s: And the Authorities Said Stop (1972) about the decommissioning of the coal mine and thus the town, Qullissat. Another documentary that describes Greenland as a developing country is Lene Aidt and Merete Borker’s Women workers in Greenland (1975).

From the beginning of the new millennium, a series of documentaries are seen that are increasingly critical of former taboos in Greenland’s history. As Greenlanders play an increasing role in the productions, the focus shifts from seeing Greenland from outside to experiencing it from within.

One of the Danes who has a critical eye on colonial power is Ulrik Holmstrup with Hingitaq – the Outcasts (2004), who, like Roos and Lynge’s films, depicts one of the black chapters of colonial history, the forced relocation of an entire population in 1953 after the establishment of the Thule Air Base. Karen Littauer made the commemorative documentary I remember … Tales from Greenland (2002), in which 14 Greenlanders tell of their childhood and youth and give a portrait of a country and its people.

Sasha Snow’s Arctic Crime & Punishment (2002) depicts a North Greenlandic community; violent crime is balanced between traditional lifestyles and a contemporary conception of crime. Laila Hansen’s Inuk Woman City Blues (2002) approaches traditional themes about the legacy of colonialism, alcoholism and rehabilitation from the perspective of women in Denmark. With The Land of Human Beings – My Film about Greenland (2006), the director Anne Regitze Wivel shows a multifaceted portrait of a country where the debate on political independence and identity is discussed. Young Greenlandic artists are in the cast, including Angu.

The television documentary The Escape from Greenland by Poul-Erik Heilbuth (2007) stirred fierce debate in Greenland over unilaterally focusing on the dark sides of society, with many calling it unethical and wrong. Another 2011 documentary, Sarah Gavron’s On the edge (2011), gave a different positive portrait of an isolated settlement which survives against all odds.

The documentary film Sume – the Sound of a Revolution (2014) with screenplay by director Inuk Silis Høegh, Emile Hertling Péronard and Ine Urheim breaks with the past. The title alludes to the band Sume that was the musical soundtrack to the struggle for home rule 1979. In an alternation of historical clips, music and interviews, the film depicts Greenlanders’ longing for freedom, co-determination and break with colonial power.

Danish-Greenlandic collaboration is seen in The Raven and the Seagull by Lasse Lau (2018), which shows Greenlandic identity’s break with the prejudices and clichés about themselves. The Fight for Greenland from 2020 by Kenneth Sorento and co-producer Jørgen Chemnitz depicts the attempts by young Greenlanders to create a new and better Greenland. Among other things, attention is focused on the independence debate and the relationship with Denmark.

The documentary Pilluarneq Ersigiunnaarpara (Happiness Scares Me No More) from 2020 by Nivi Pedersen focuses on life after sexual assault as part of Killiliisa, Naalakkersuisut’s strategy against sexual assault.

The years of collaboration

In the years from the mid-1950s and to the late 1990s, it was especially the collaboration between Denmark and Greenland that characterised Greenlandic films. Qivitoq (The Mountain Wanderer) from 1956, directed by Erik Balling, focuses on a familiar theme about Greenland as the country where the traveller can find himself again after defeat in Denmark – and at the same time the film highlights the difficult local transition from the hunting to the fishing profession. Qivitoq has a Danish and Greenlandic cast, including Greenland’s first film star, Niels Platou.

The collaboration continued with Palle Kjærulff-Schmidt’s Tukuma with screenplay by Palle Kjærulff-Schmidt, Klaus Rifbjerg, Josef Tuusi Motzfeldt and Greenlandic actors from the Tuukkaq Theatre. The theme is familiar; personal crisis, suicide attempts and the journey to Greenland in a search for identity.

Self-representation and collaborative production

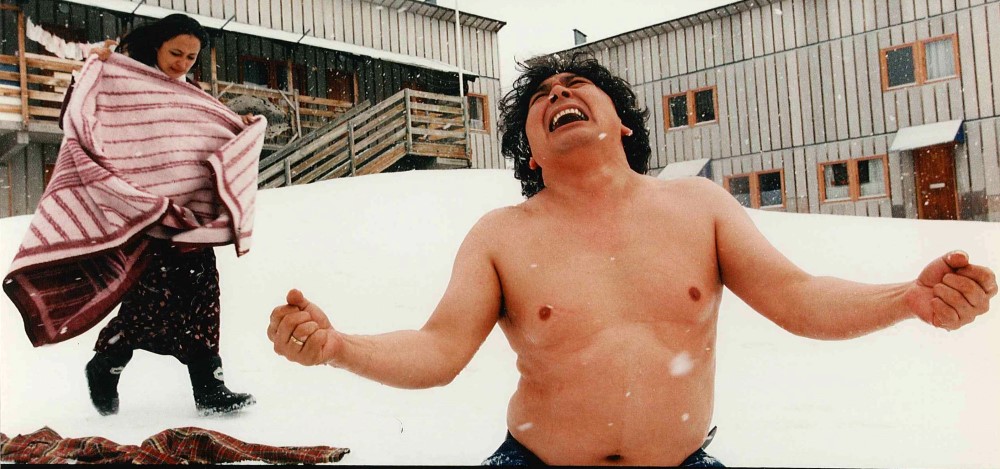

The 1980s and 1990s mark the beginning of Danish-Greenlandic collaborative productions that deal with both Greenlandic and more universal themes. Heart of Light from 1998 by Jacob Grønlykke with screenplay by Grønlykke and Hans Anthon Lynge marked a milestone: It was filmed in Greenland, the language was Greenlandic and a number of well-known Greenlandic actors were in the cast. The drama deals with a family tragedy against the backdrop of colonialism, alcoholism and the search for identity in the wild nature.

The collaborative films paved the way for the first generation of Greenlandic filmmakers, and their works began to appear at the turn of the millennium. The films had more and more Greenlandic cast members: writers, directors, producers, actors. The topics reflected that the young generation wanted more than colonial history.

ASA FILM PRODUCTION/DET DANSKE FILMINSTITUT, 1998

Films such as Inuk Silis Høegh’s Sinilluarit (1999) and Eskimo Weekend (2002) broke with depictions of Greenland as a troubled or exotic country. Instead, these short films show an ordinary youth weekend filled with jealousy, romance and happy end. A particularly Greenlandic dispute is felt when two young rivals ‘outsing’ each other as in the traditional singing duels.

The feature film Hinnarik Sinnattunilu (2009), directed by Angajo Lennert-Sandgreen who also plays the lead role, has become cult among Greenlandic children. The film is produced by Aka Hansen and Malik Kleist in their own production company Tumit Production. Nuummioq by Torben Bech and Otto Rosing also came in 2009, and like Hinnarik Sinnattunilu, it marks a break with the focus on the past and past inherited problems seen in Heart of Light and in the French-Greenlandic collaboration Inuk (Le Voyage d’Inuk) by Mike Magidson (2010). On the visual and thematic level, Nuummioq breaks with the stereotypical notions of Greenland and individually describes general human events such as love and sickness.

Between the series of Greenlandic films, another Danish film is seen with a critical view of Greenland’s colonial history, The Experiment from 2010, directed by Louise Friedberg from a screenplay by Friedberg and Rikke de Fine Licht. The film tells the story of 22 Greenlandic children who, as part of a Danish-Greenlandic experiment in 1951, were sent to Denmark to be raised to be elite Greenlanders. The film, inspired by Tine Bryld and Per Folkver’s interview book I den bedste mening (With the Best of Intentions) (1998), led to demands for Denmark to apologise.

Young film industry

ULANNAQ INGEMANN/POLARAMA GREENLAND, 2018

The first Greenlandic youth horror movies, the hit Qaqqat alanngui (2011), is directed by Malik Kleist. The film easily measures up to American horror movies, and arguably there are many international references, but the horror also draws on Greenlandic aesthetics and cultural history: The murderer, who is a qivittoq (mountain wanderer), one by one murders the young people out in the Greenlandic nature.

By the same director, Malik Kleist, came Unnuap Taarnerpaaffiani (When The Darkness Comes) in 2014. Also this film is completely Greenlandic in terms of director, production, cast and language. Although the horror elements are worthy of an international horror film, however, there is a special Greenlandic vibe with monsters from Greenlandic mythology. One of the newest feature films is Pipaluk Kreutzmann Jørgensen’s film Anori (2018) which she has written, produced and directed. The film blends a tragic love story with old Greenlandic myths, and featuring Nukâka Coster-Waldau as Anori, the film has a series of dreamlike sequences set in Greenland and views to New York.

With these films, a young film industry has also blossomed up with the creation of Tumit Production, film.gl and Polarama Greenland, which aim to professionalise the local film industry and create entirely Greenlandic produced films. The film language is now more varied with looks at both past, present and future.

Further reading

- Industry and labour market

- Language

- Makka Kleist

- Population and demographics

- The colonial period until the war years

- The media in Greenland

- The polar explorer Knud Rasmussen

- Theatre and dance

- Traditions and tales

Read more about Culture in Greenland